Home › Forums › The Colonial Era › The Enslaved People of Riverdale, Kingsbridge, and Spuyten Duyvil › Reply To: The Enslaved People of Riverdale, Kingsbridge, and Spuyten Duyvil

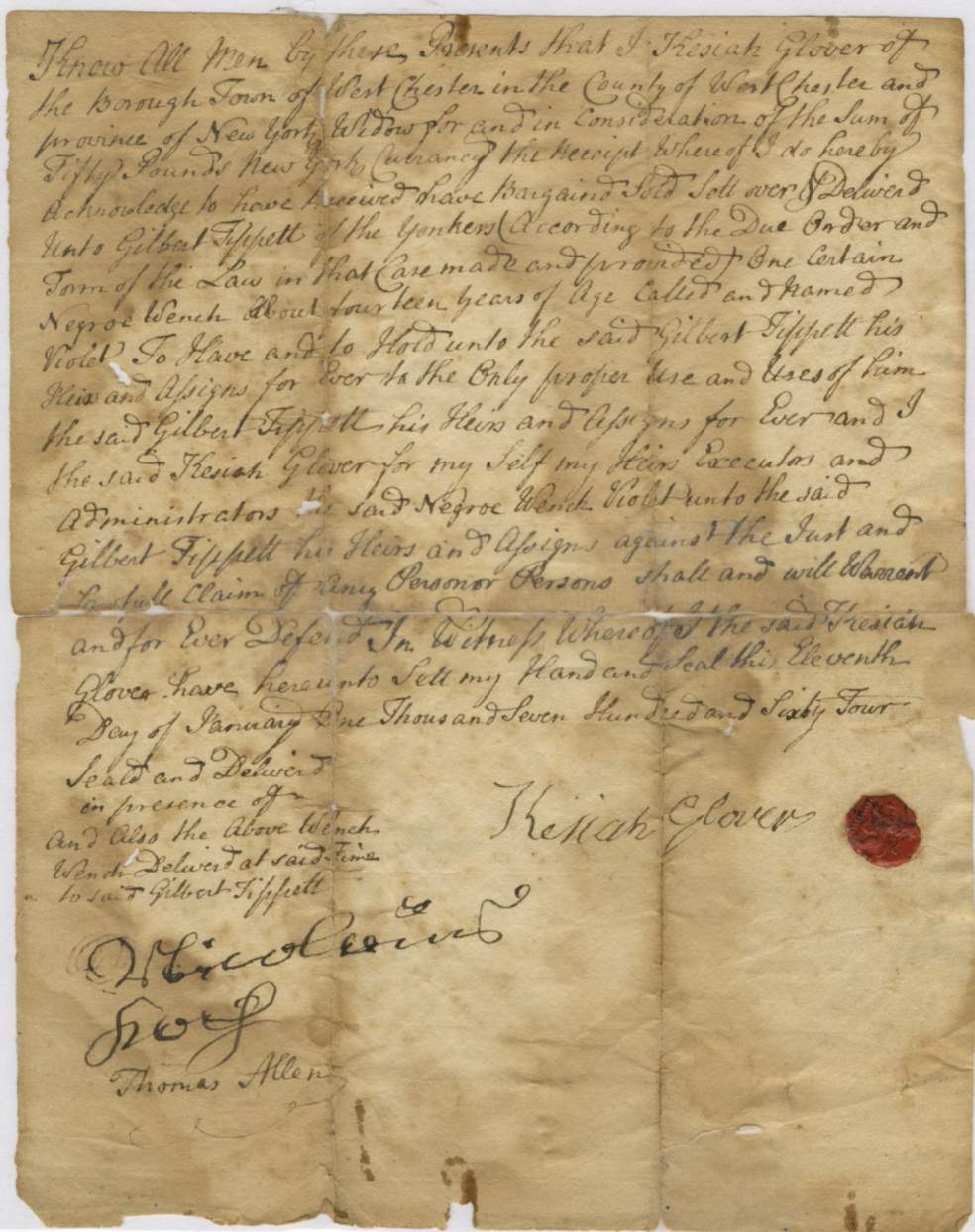

The above-mentioned George Tippett’s great-grandson, Gilbert Tippett, lived in Spuyten Duyvil during the American Revolution. Gilbert’s story is very interesting and long so I won’t get into it all but he was a loyalist, who eventually lost his lands after the revolution. Not too long ago, I learned that Gilbert held an enslaved person when I stumbled across this document in an online auction:

It indicates that Kesiah Glover of Westchester sold a 14 year old girl named Violet to Gilbert Tippett in 1764 for 50 pounds (New York Currency). The document describes her as “One Certain Negroe Wench About fourteen years of Age Called and Named Violet.” According to another document of the same date, Kesiah Glover got into some legal trouble and was ordered to pay James Ferris (of Westchester) 100 pounds. Gilbert Tippett was to sell Violet if Kesiah Glover was unable to pay what she owed to Mr. Ferris. In summary, Gilbert Tippett procured a slave that he was holding in escrow for Kesiah Glover–but in the meantime Gilbert “owned” this enslaved person. The legal language of this transaction for a 14 year old girl sends a chill up the spine as she is treated as any commodity.

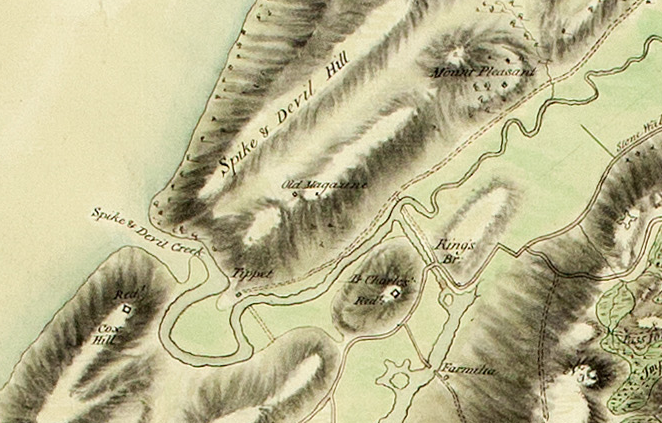

There is no way of knowing what life was like for Violet other than the location of her home. According to the will of Gilbert Tippett’s grandfather, Gilbert’s property was on the east half of Spuyten Duyvil neck–sometimes referred to as “Tippett’s Neck.” Maps from the revolution indicate a couple of structures in that area. The below map, a screenshot taken from the Clements Library digital collection, shows a building on the Spuyten Duyvil Creek west of Marble Hill. This is where Violet probably lived with Gilbert Tippett. During the revolution, Gilbert operated a ferry at Spuyten Duyvil close to this spot.

In this other map from 1781, also from the Clement’s Library, the structure is labeled as belonging to “Tippet.”

Today, the site of Gilbert Tippett’s home might no longer exist. As you can see in the previous maps, it was situated on a peninsula surrounded on three sides by the Spuyten Duyvil Creek. That peninsula was eradicated when the Harlem River Ship Canal was cut through that land. Below is a current map depicting the canal. For some reason, Google labels this waterway “Spuyten Duyvil Creek” despite the fact that it is no longer a “creek” but a wide, deep, and turbid canal.

At some point between the date of her purchase by Gilbert and the end of the American Revolution, Violet ceased to be in Gilbert’s “possession.” But Gilbert’s slave-holding did not end with Violet. We know these things because of certain events that occurred at the conclusion of the American Revolution.

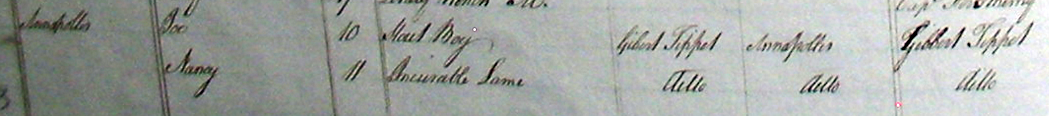

Throughout the war, the British had hoped to entice enslaved Black people to flee their patriot masters and join the loyalist cause. Many did so and ended up in British-held New York until the end of the war in 1783. According to the Treaty of Paris, which ended the war, the British were supposed to return the formerly enslaved refugees to their American masters. However, Sir Guy Carleton, then Commander in Chief of British forces, refused to comply with the provision and did not return the Black refugees. According to Carleton, it “would be a dishonorable Violation of the public Faith pledged to the Negroes” to return the enslaved people to their captors and subject them to “Execution and others to severe Punishment.” Therefore, when white loyalists fled New York for Nova Scotia in 1783, many who had escaped slavery from patriot “masters” kept their freedom and went along with them. To America’s patriot leaders, this was an outrage. James Madison denounced Carleton’s actions as Black refugees, such as Harry Washington, who had escaped from George Washington, were allowed to retain their freedom in Nova Scotia and the Caribbean. Those enslaved by loyalists, however, were not as lucky. The British allowed loyalists to keep enslaved people in bondage elsewhere in the empire after fleeing New York. Slave or free, all of the Black people that were evacuated from New York in 1783 on British ships had their personal information recorded in a document called the “Book of Negroes,” which was created in the event that the British were forced to return the formerly enslaved people to their patriot masters. In this book, two Black children, Joe and Nancy (aged 10 and 11 respectively), are recorded as slaves belonging to “Gilbert Tippet.” They set sail aboard the Joseph in March of 1783 bound for Annapolis, Nova Scotia. Joe is described as a “stout boy” and Nancy as “incurably lame.”

That is all we know about Joe and Nancy. Could they have been the children of the aforementioned Violet? Possibly. She would have been about 23 years old in 1773 when Joe was born. If the children grew up in the house at the Spuyten Duyvil Creek they would have witnessed their “master’s” temporary imprisonment by the patriots for speaking ill of the patriot army in 1776. They would have seen the British army fight their way past their home in the Battle of Fort Washington later that year. They would have lived next to a Hessian garrison and heard many skirmishes fought in the area around their home. Perhaps they even encountered an unexpected visitor on July 14, 1781. On that date, Washington sent very specific orders to Colonel Alexander Scammell of his elite light infantry. Washington wrote, “At the mouth of Spiten Devil, it must be observed whither any Water Craft lies there, whether any Person lives in the House at the Point.” At that time, Washington was planning an assault on New York City through Kingsbridge that never came to pass. As the war came to a close, the enslaved children would have been taken to the city where they would board the Joseph and set sail for Annapolis, Nova Scotia. I would not imagine the world made very much sense to Joe and Nancy. Interestingly, aboard the same ship, according to the “Book of Negroes,” was a Black refugee named Violet Moore listed at 30 years old from New York–formerly enslaved by William Hedden (a common surname in the area around Westchester). There is no evidence to indicate that this is the same Violet once held by Gilbert Tippett–just the first name is the same and the age roughly fits.

According to a 1784 census of Annapolis, Nova Scotia, Gilbert Tippett had one “servant.” It is not clear if this was Joe, Nancy, or someone else. The Tippetts must not have loved life in Nova Scotia as they moved back to New York and settled in the Albany area. An 1800 census records “Gilbert Tippets” as a resident of Ballston, NY, where he lived with his wife, Susannah. The household is recorded as having had enslaved people. It is therefore unknown what happened to Violet, Joe, and Nancy.