Historic Black Kingsbridge 1698-1850

A Community Revealed in Documents

Part One - Van Cortlandt Plantation

12/9/18 – Nick Dembowski

If you are familiar with the history of Kingsbridge, Riverdale, and Spuyten Duyvil, you probably already know that the area was first settled by Dutch and English settlers, who purchased the land from Native Americans. If you are like me, you may have assumed that the area remained a white neighborhood thereafter until the 1960’s and 70’s when the neighborhood began to diversify. Nothing that I read in local history books said any different. But that assumption turned out to be inaccurate. The truth was out there but it was buried in dusty tomes in the municipal archives and on handwritten parchments in research libraries. But the truest witness to this hidden past is buried in a far more familiar place–under the Putnam Trail in Van Cortlandt Park.

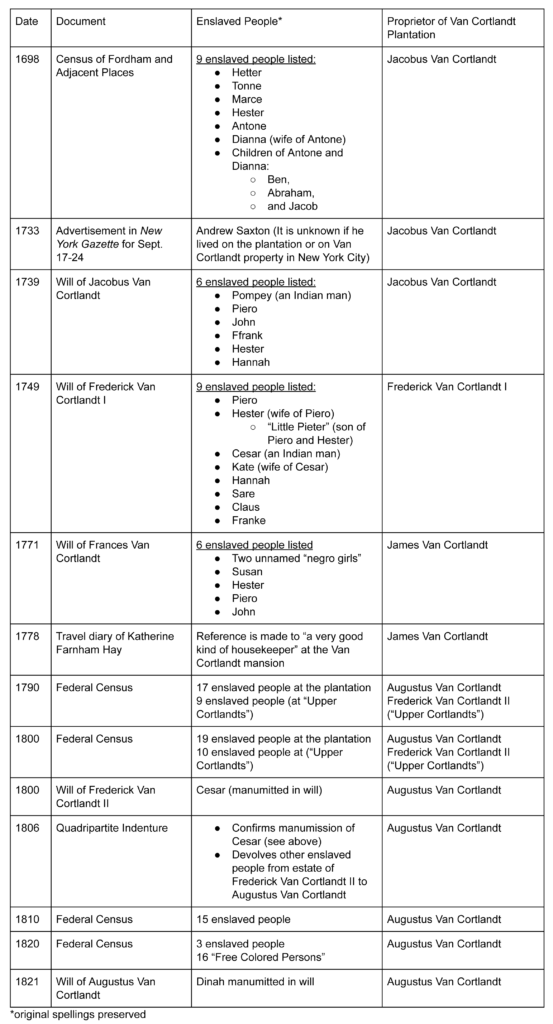

Historical documents reveal that the Black population of Kingsbridge was proportionally much higher in the distant past than it is today. Census lists show this demographic reality in stark numbers (see Appendix A). Wills, “runaway” ads, indentures, and estate inventories give a fragmentary glimpse as to who these early Africans of Kingsbridge were–sometimes providing their names, their occupations and family relationships. These documents are few in number and only provide hints of the lives led by the Black inhabitants of Kingsbridge. There are no surviving diaries or letters written by Black people that lived in the area because they were an enslaved population. The information that we do have concerning the historic Black community is entirely from the perspective of European colonists. As a result, these documents paint a very fragmentary and incomplete picture of the lives of locally enslaved Africans. What motivated them, their relationships, their beliefs–almost everything that makes them individuals–was not recorded in documents pertaining to this particular neighborhood. But the documents do reveal the existence of the community. They also show that the largest concentration of enslaved people in the area lived and worked on Van Cortlandt Plantation (see Appendix B). As a disclaimer, I am not an expert on slavery, the African diaspora, or African American history. My hope is, that in bringing the existence of these documents and this community to light, that the story will be studied further by others.

...the Black population

of Kingsbridge was proportionally much higher in the distant past than it is today...

And at this time there is an urgent need for further study. Recently uncovered evidence (detailed below) suggests the existence of an unmarked African burial ground in Van Cortlandt Park along the Putnam Trail. Currently, there are plans to pave over a section of that historic burial ground in early 2019. It is important to share and publicize this information in order to prompt an archaeological study before the project proceeds. [Note: See update at the end of the article.]

An Early Census - 1698

When we learn of American pioneers, images of enslaved Black people are rarely depicted. But in 1698, enslaved Africans in the West Bronx were already doing the same kind of work as later pioneers. Enslaved workers were felling trees, clearing land, building roads, constructing buildings, and transforming the landscape.

We learn of an African presence in the first surviving census–the 1698 Census of Fordham and Adjacent Places, which encompasses today’s West Bronx. We find the names of some of the first colonial settlers in the neighborhood, such as the Tippett family. The members of the family are listed along with “one slave Adum.” There is also the Van Cherreck family along with the enslaved Africans “hetter, tone, marce,” and “ester”. These enslaved people are listed among a cluster of settler families that were living in today’s Van Cortlandt Park not far from the Van Cortlandt mansion, which had not yet been built. But Jacobus Van Cortlandt had already begun acquiring land in the area. Included in the census are the enslaved Africans that worked for “Mr. Cortlant: “hetter, tonne, marce, hester. antone the negerr and dianna his wife and three children: ben, abraham, Jacob.“ Curiously, there are no members of the Van Cortlandt family listed on the census. This suggests that work on the Van Cortlandt lands must have been supervised by a local overseer–possibly Johannis Van Cherreck.1 The owner of the land, Jacobus Van Cortlandt, was still living in lower Manhattan, where he worked as a merchant and served as mayor of New York City for two terms. His import/export business earned the fortunes necessary to purchase land for Van Cortlandt Plantation. That business dealt in cloth, manufactured goods, and small numbers of enslaved Africans.2

Around this time, the local leg of the Albany Post Road was made. The colonial government did not hire contractors to do the work as is done today. Rather, people that lived near the route were required to help construct the road.3 It is hard to imagine Jacobus van Cortlandt, a wealthy New York merchant and politician, wielding the pick and shovel required for this project when he didn’t even live in the area. As was true elsewhere in the colony, the enslaved people likely built the road. This strategic road, which connected New York City to Albany, started its journey through The Bronx at the King’s Bridge and headed north into today’s Yonkers. The road carefully navigated the marshy lands of the Kingsbridge valley as it wound its way through contemporary Van Cortlandt Park.

Van Cortlandt Plantation

In the early colonial period, while Jacobus Van Cortlandt was living in New York City, his enslaved labor force laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the Van Cortlandt Plantation4 in the West Bronx. These enslaved workers dammed Tibbett’s Brook to create the mill pond that is known as Van Cortlandt Lake today. This was done to increase power to the gristmill and sawmill that were built at the south end of the lake. 40 years after that first census was taken, a new list of names is revealed in the will of Jacobus Van Cortlandt. He bequeathed to his son, Frederick, the “Indian Man Slave named Pompey.” Native American enslavement was not unheard of in the area.5 Additionally, Jacobus bequeathed to Frederick “three Negro men Slaves called Piero John and Frank and . . . two Negro Women Hester & Hannah togr. with all the Children that are already or hereafter shall be born of the Body of the said Negro Woman named Hester.”6 There is little doubt that enslaved laborers, including the above-named people, were employed in the construction of Van Cortlandt mansion, which was funded by Frederick Van Cortlandt. At the time of Frederick’s death in 1749, the mansion was nearing completion.

The plantation on which I now live will . . . devolve after my decease on my eldest Son James wherefore I give and Bequeath unto him . . . my Negro Man Levellie the Boatman. I do also give and bequeath unto my Son James the following Negro Slaves to witt piero the Miller and Hester his Wife and little Pieter the Son of Piero with my Indian man Cesar and Kate his wife.7

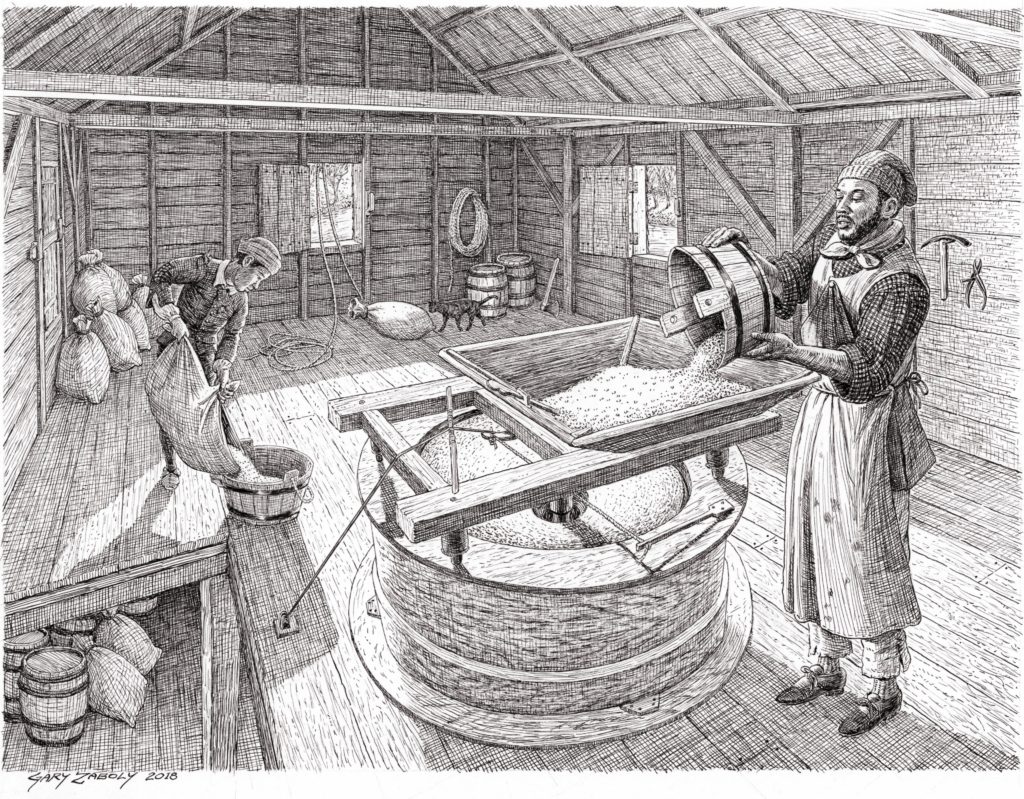

The above individuals would have represented a very valuable part of James’ inheritance. Enslaved servants and farmhands were valuable but an enslaved miller would have been key to ensuring big profits from the plantation. While the word “plantation” often conjures up images of large fields of cash crops like cotton, indigo, or tobacco, the Van Cortlandts operated what is called a provisioning plantation. In other words, they were producing food to sell on the open market or for export. By owning their own gristmill, sawmill, and miller, the Van Cortlandts had another revenue stream at the plantation. Milling was a skilled trade–one that would require years of learning through apprenticeship. It was not a simple matter of pouring wheat into a machine but also of maintaining and calibrating a complex piece of equipment. As millstones ground down, they would routinely need to be removed to be “dressed.” This means lifting and flipping over the runner stone (weighing over 1000 pounds) to have grooves precisely recarved. Without going into the process, it suffices to say that the Van Cortlandts profited mightily from not having to pay for the skilled labor. It is probable that neighboring farmers brought their grains to the Van Cortlandt mills to be milled by Piero, who would take a portion of the flour as payment to the Van Cortlandts (as was true at other local mills). Perhaps his value to the family was what made it possible for him to have a wife (Hester) and child (Peter) on the plantation while other enslaved people did not.

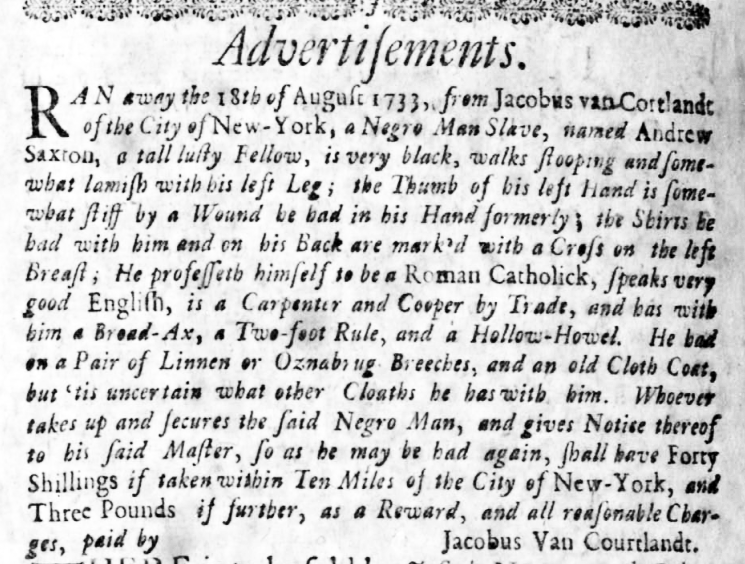

A “runaway” ad in the New York Gazette from September 17, 1733 shows that the Van Cortlandts profited from skilled slave labor in more than one way. Andrew Saxton, as a cooper, provided a skill that was in high demand in colonial New York–making barrels. Having an enslaved cooper meant the Van Cortlandts would not have to pay market rates for this skill either. This was another job that typically required an apprenticeship to master. Advertisements such as this one are the closest thing many enslaved people have to a biography in the historical record. However, rather than satisfying your curiosity about the individual, details like a “stooping” walk and “a Wound he had in his Hand” only raise more questions about their lives.

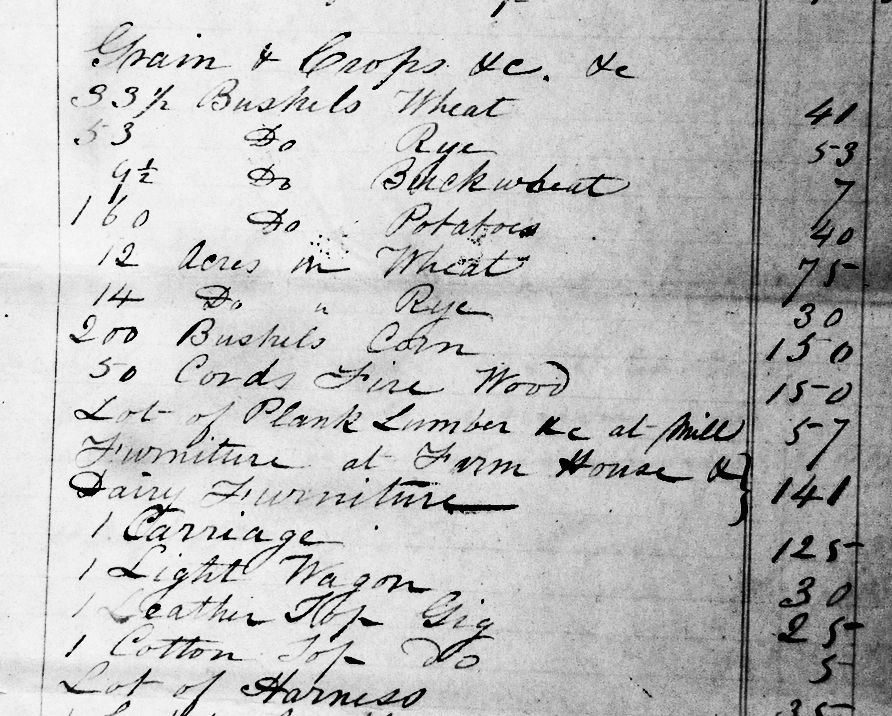

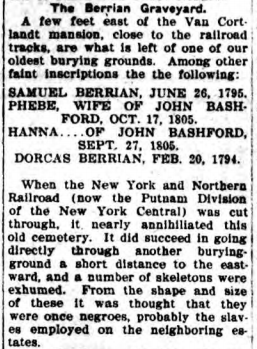

Selections from 1839 estate inventory of Augustus Van Cortlandt

Taken as a whole, Van Cortlandt plantation is a microcosm of a large part of the New York economy in the colonial period. Much of what occurred here is mirrored by the seal of the City of New York, which pays tribute to this economy as the source of New York’s wealth. A Dutchman is represented–not unlike Jacobus Van Cortlandt. Depicted on the shield between the Dutchman and the Native American are the blades of a windmill used for milling wheat. In the middle of the shield are the barrels, likely filled with flour. In the case of Van Cortlandt plantation, that flour barrel could have been made by Andrew Saxton. The flour could have been milled by Piero and the wheat could have been planted and harvested by the many other enslaved people working on the plantation. Levellie the enslaved boatman could have taken those barrels to market. Once loaded on a ship, that flour was most likely destined to the Caribbean to provision its enslaved workforce while profits flowed up to the Van Cortlandt family.9 The fact that this industry is enshrined in the seal indicates the scale of the profit involved and its importance to the region’s development. One thing missing from the seal is any representation of the enslaved Black workforce that made that economy possible.

"Upper Cortlandts"

I hereby manumit and release from Slavery my negro man called Cesar for his Fidelity towards me and for his Honesty Sobriety and Industry . . . my Executors and the survivor of them are hereby authorized and required to place at Interest out of my Estate the sum of five hundred Spanish milled Dollars or pieces of Eight and the said interest arising therefrom to be paid annually to my said Negro man called Cesar during his natural Life.13

An 1806 indenture between the heirs of Frederick Van Cortlandt II shows that they complied with his wishes to free Cesar and provide him with income.14 As for the other enslaved workers at Upper Cortlandts, they were devolved to Augustus on the main plantation after Frederick II’s death.

Gradual Emancipation

Under the administration of Augustus, work at Van Cortlandt Plantation continued in the early 1800’s as evidenced by the agricultural output revealed in the estate inventory. Emancipation was a gradual process on the plantation, as it was in all of New York. This was by design. In 1799, the Gradual Emancipation Act was passed in the New York State Legislature. The act freed the children of enslaved people that were born after July 4, 1799–but not immediately. They would only be set free after reaching a certain age (25 for women and 28 for men). The 1800 census reveals an increase in the enslaved population at the plantation from 17 in 1790 to 19 in 1800. But the enslaved workforce at Van Cortlandt Plantation decreased from then on. The 1820 census reveals 3 enslaved and 16 free Black people at the plantation. In Augustus’ 1821 will, he manumitted his “Negro Slave Dinah in consideration of the great care and attention she paid my deceased affectionate wife during her last illness.”15 By the 1830 census there were four free Black people living at the plantation. In all of Yonkers there was one enslaved person listed on the 1830 census.

By 1850 the Black community of Kingsbridge almost completely vanished–composing less than 1% of the population. This is a precipitous decrease from half of a century earlier when the same community seems to have numbered over 20% of the population. Perhaps the lure of Black society in New York City drew them to the city. Perhaps there was no affordable place to live in Kingsbridge. Or maybe these free people just did not want to remain in the same place where they were enslaved.

Peter, Piero's Son?

The 1830 and 1840 censuses, which punctuate the decline of the Black population in Kingsbridge contain interesting details in the names of the few Black individuals and families that remained. Their last names were finally legally recorded. But where did those last names come from? According to Henry Louis Gates, last names “could have several possible origins. With the abolition of slavery, many black people had the opportunity to start their life anew and choose their own surname. While it is true that some adopted the name of their former owners, this was not always the case . . . Other surnames were based on family members’ given names.”16 I was taken with this idea when I came across the following Black individual listed on the census. “Peter Pirson” appears in the census among households on the Albany Post Road by the Van Cortlandt plantation. Something about the name “Pirson” stood out to me. There certainly were not any local landowners named Pierson. Could it possibly be a name chosen to mean “Piero’s son?”–Piero, who was the miller at the Van Cortlandt mills? Piero did indeed have a son named Peter and this person on the census is recorded as between 55-100 years old. In the 1830 census there is a woman named Hester Pirson recorded as the head of this same household. Hester and “little Pieter” were the names of Piero’s wife and child according to Frederick Van Cortlandt’s 1749 will. It seems possible that these people could be the descendants of the enslaved family listed in Frederick Van Cortlandt’s will 90 years earlier.17

Enslaved African Burial Ground in Van Cortlandt Park

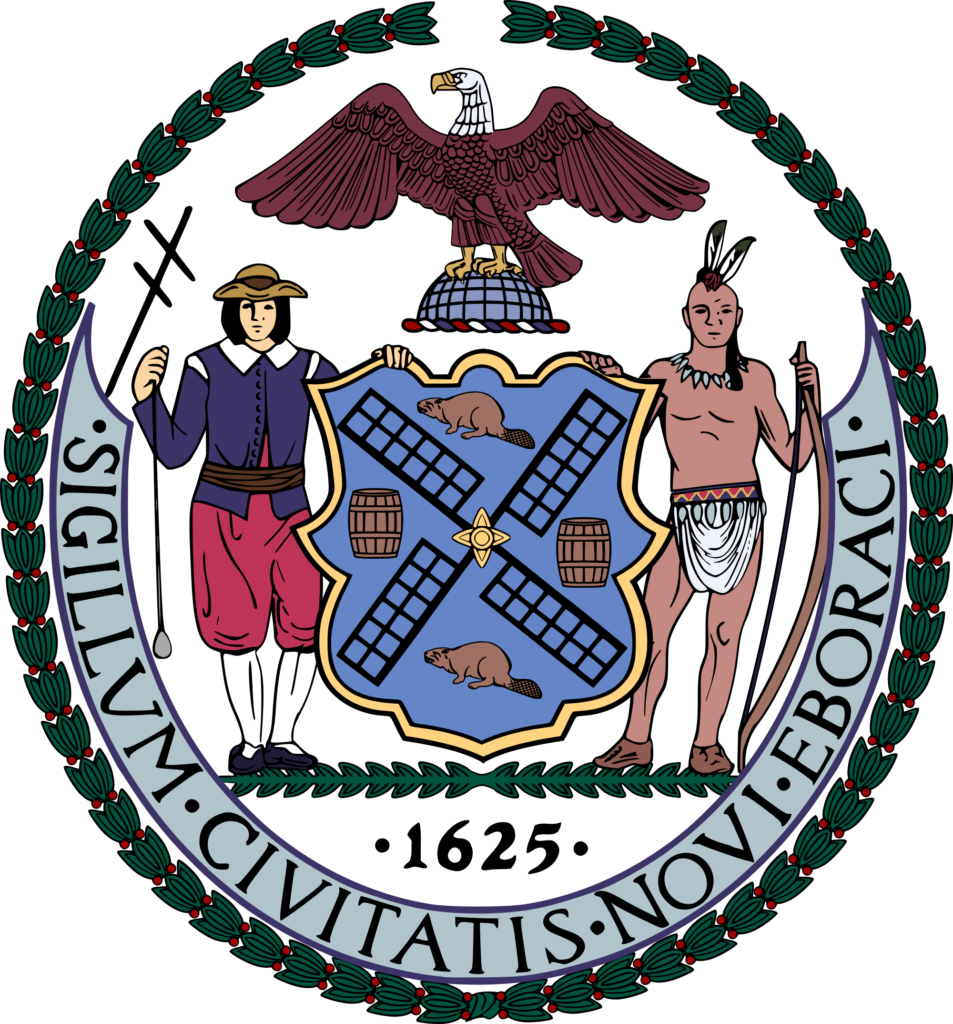

One of the most beautiful and serene places in all of The Bronx is certainly along the Putnam Rail Trail on the western bank of Van Cortlandt Lake. It is a place enjoyed by runners, hikers, local fisherman and all kinds of wildlife. Recently unearthed historical documents suggest that this spot may have been a place of great significance for the neighborhood’s historic Black community. Further to the west of the lake at a higher elevation is what remains of the Kingsbridge burial ground (a.k.a. Berrian-Tippett burial ground).19 It is an old family cemetery laid out in the colonial period. The eastern boundary of that cemetery was legally declared to be the bank of the lake. This suggests that the rail trail, running along that bank, traverses part of the cemetery. Old local histories claimed that the eastern part of the cemetery along the banks of the lake was used by the local enslaved population.20 However, it was always unclear if there was any basis to the story.

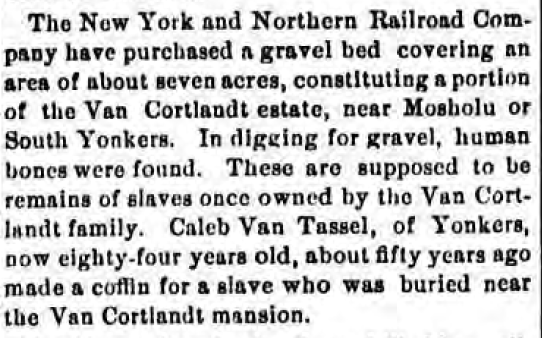

A long forgotten but recently unearthed article about old Bronx cemeteries (right) seems to confirm this story. It reports that the skeletons of deceased Africans were dug up when the railroad was built along Van Cortlandt Lake. This clipping raises as many questions as it does answers but it jibes with old local histories–that the eastern part of the Kingsbridge Burial Ground was where the neighborhood’s enslaved Africans are buried. The likelihood of this fact is bolstered by its consistency with a pattern. Historic Black cemeteries were often adjacent to cemeteries for white colonists–sometimes near water and often at lower elevation. You don’t need to look farther than the Hunts Point Slave Burial Ground in The Bronx to find a similar example. Adding to the spiritual significance of the site is the fact that New York’s colonial government forbade gatherings of Black people that numbered more than a few individuals. There was no way for the community to congregate legally. An exception to this law was for funerals. In addition to being a sacred space, this may have been the only place where the Black community of Kingsbridge could be together in one place–adjacent to the beautiful mill pond that was built by their enslaved African brethren.

Additionally, this spot is a few short steps away from the location of the Van Cortlandt mills, where Piero, the enslaved miller worked. It is probable that the enslaved workers from neighboring farms would come here to bring grain to be milled or to retrieve lumber from the sawmill. This would have been a place where enslaved people, who were isolated on rural farms might have chance encounters with other Black folks in the neighborhood. Looking at this fact in concert with the nearby cemetery and lake, it seems this could have been the center of the historic Black community.

The 1905 article suggests that the skeletal remains were dug up on the very spot that is about to be paved over. Paving typically involves some shallow digging and laying of gravel. In light of emerging evidence about the burial ground, there needs to be an archaeological study performed before proceeding with this project. Using remote sensing equipment, this can be done without disturbing any potential remains. Such archaeological work could do a lot to make park-goers aware of the lasting contributions of the local enslaved community and perhaps cause them to consider the lives of people like Piero, Hester his wife, and their son, little Pieter.

Update

In early 2019, soil scientists from the US Dept. of Agriculture brought ground penetrating radar equipment to Van Cortlandt Park and scanned the area by the burial ground to look for evidence of burial sites. The scientists’ analysis and report was completed that summer. Four sections were scanned and studied. First, a section of the White colonists’ burial ground was scanned and it revealed soil disturbances that could indicate burial sites. Second, a larger area to the north and east of the colonists’ burial ground was scanned. According to the above 1905 newspaper article, this was the burial place for “negroes, probably the slaves employed on the neighboring estates.” The scanning revealed similar patterns to the potential burial sites in the colonists’ burial ground. Third, a dirt trail adjacent to the southern edge of the colonists’ burial ground was scanned. This also revealed similar soil disturbances. Lastly, a large section of the Putnam Trail was scanned. This revealed nothing like the soil disturbances in the previous three locations. This all seems to indicate, that there are no burials under the Putnam Trail but that there are burial sites around in the fenced-off section of the colonists’ burial ground and even more burial sites beyond the fence. Are these external burial sites to the northeast the final resting places of the enslaved African community? The findings do seem to corroborate what was written in the 1905 article.

6/17/19 Addendum:

An additional article has just come to light that documents the existence of the African Burial Ground in Van Cortlandt Park. It appeared under the title “Railroad Matters” in the September 25, 1879 edition of the Portchester Journal (although the same article appeared in many other local papers at this time). While the level of detail leaves much to be desired, the testimony of Caleb Van Tassel, who lived in and around Van Cortlandt Park, is noteworthy. He was an eye-witness to the last days of slavery on Van Cortlandt Plantation.

Please feel free to comment here.

Special thanks to Patrick Raftery at the Westchester County Historical Society and Jackie Graziano at the Westchester County Archives for finding many of these documents.

Notes and references:

1 – The names of the enslaved listed under Van Cherreck are nearly identical to part of the Van Cortlandt list suggesting that Van Cherreck may have been the aforementioned overseer.

2 – Letter Book of Jacobus Van Cortlandt, New York Historical Society MSS. June 6, 1698 Letter to Mr. Witt.

3 – New York (Colony), Charles Zebina Lincoln. The Colonial Laws of New York from the Year 1664 to the Revolution, Including the Charters to the Duke of York, the Commissions and Instructions to Colonial Governors, the Duke’s Laws, the Laws of the Dongan and Leisler Assemblies, the Charters of Albany and New York and the Acts of the Colonial Legislatures from 1691 to 1775 Inclusive, Volume 1. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2006. p. 27.

4 – Jacobus Van Cortlandt’s son, Frederick, refers to his property in the area as his “plantation” in his 1749 will.

5 – I have found other Westchester wills and deeds that refer to enslaved Native Americans. One such deed, Westchester Liber D 27, even uses the term “Negro” to describe such an enslaved Native Americans.

6 – Will of Jacobus Van Cortlandt, 1739, New York Wills, Vol. 13, 1736-1740, p. 425.

7 – Will of Frederick Van Cortlandt, 1749, New York Wills, Vol. 18, 1751-1754, p. 61.

8 – Estate Inventory of Augustus Van Cortlandt, 1839. Westchester County Archives.

9 – Peter Kalm, Travels into North America (1749), 1, 253-8; 243-5; reprinted in Guy Stevens Callender (ed.), Selections from the Economic History of the United States, 1765-1860 (Boston: Ginn and Co., 1909), 16-20.

10 – Ondine E. Le Blanc and Katharine Farnham Hay, The Journal of the “Rebel Lady”: Katharine Farnham Hay’s Account of Her Trip to New York City, 1778. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, Vol. 109 (1997), pp. 102-122.

11 – Will of Frances Van Cortlandt, 1771, New York Wills, Vol. 34, 1780-1782, p. 43.

12 – March 2, 1843 Letter from J.G. Dyckman to Luther Bradish – New York Historical Society MSS.

13 – Will of Frederick Van Cortlandt, 1800, New York Wills, Vol. 49, 1809-1811, p. 334.

14 – Quadripartite Indenture between John Jay, Augustus Van Cortlandt and other dated June 22, 1806. Columbia University Library Manuscripts Division.

15 – Will of Augustus Van Cortlandt, 1821, County of Westchester Wills, Vol. K, 1822-1826, p. 180.

16 – “Lost Slave Ancestors Found.” theroot.com, November 29, 2013, https://www.theroot.com/lost-slave-ancestors-found-1790899106

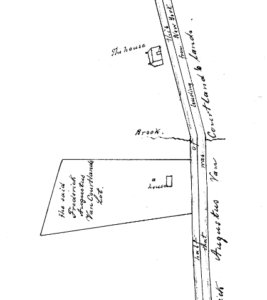

17 – Adding to the intrigue about Peter and Hester Pirson’s ancestry is the location of their home. By looking at the names above and below their line in the census, it is clear that they lived along the Albany Post Road somewhere in the vicinity of West 251st Street. The Van Cortlandts owned a sliver of land on the west side of the Albany Post Road where a house stood before (and well after) the American Revolution. It can be seen in the quadrilateral in the below surveyor’s map from 1829. The north-south road is the Albany Post Road.

According to the Historical Guide to the City of New York, this was the “Van Cortlandt’s Miller’s House, a white house built for the miller of the old estate.” Could these people be descendants of Piero the Miller still living in the ‘Van Cortlandt’s Miller’s House” in the 1840’s?

18 – Rael, Patrick. “The Long Death of Slavery.” Slavery in New York. Ed. Berlin, Ira and Harris, Leslie M. New York, The New Press, 2005. pp 131-133.

19 – This is a family cemetery laid out to the descendants of William Betts and George Tippett in Westchester County Deed Liber E-147. The boundaries of the cemetery were legally demarcated in a 1732 Westchester County land deed, Liber G-30, between George Tippett and Jacobus Van Cortlandt. The deed transfers Tippett’s “home lott” to Van Cortlandt but exempts ½ acre of his land from the sale so that it can remain “a burying place for their use forever.” An interesting side-note to the story is the question of who actually owns the land today. The land was never actually owned by the Van Cortlandts. When the Van Cortlandts sold their land to the city to create the park, this burial ground land could not have been part of the deal as it was still owned by the descendants of William Betts and George Tippett.

20 – Kelly, Frank Bergen. The Historical Guide to the City of New York. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company Publishers, 1909. p. 182. – It is worth noting that this book was edited by Reginald Pelham Bolton and Edmund Hagaman Hall. They were legit local historians that did not peddle in fabricated history. This gives credence to the claim that east of the Kingsbridge Burial Ground along the lake “was the negro burying ground, where the slaves of the early owners were interred.”

Appendix A:

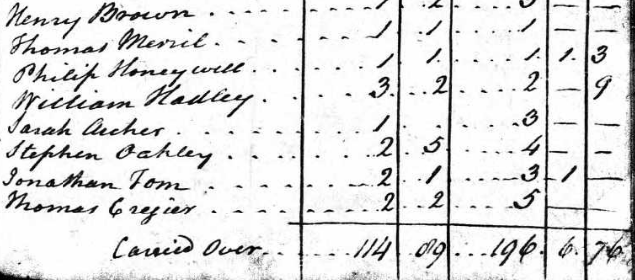

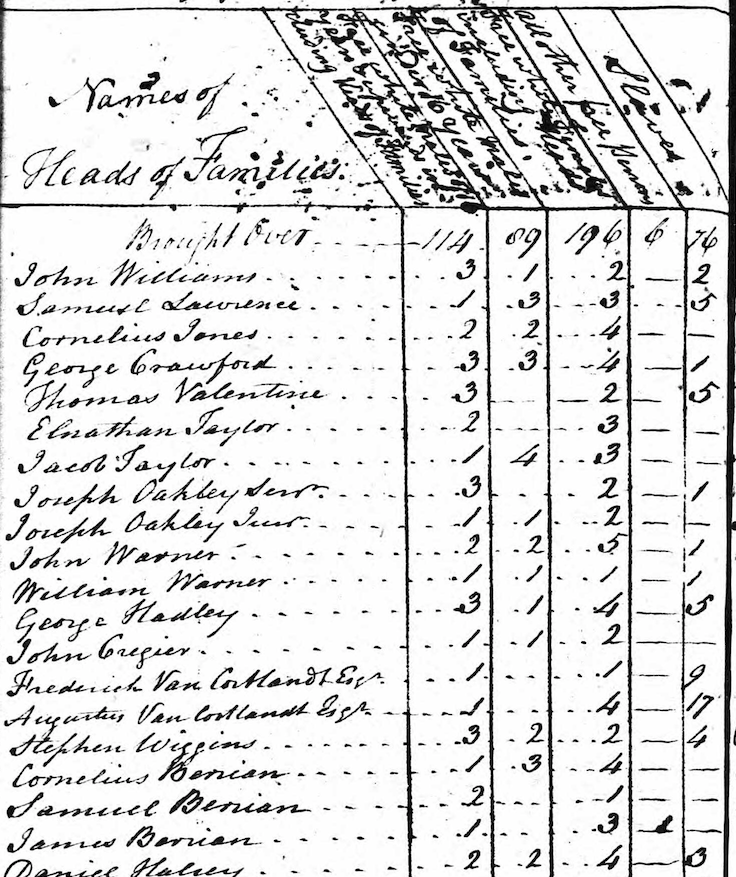

1790 Census Fragment for South Yonkers (Today’s Riverdale, Kingsbridge, and Spuyten Duyvil)

It will not be possible to gather exact demographic statistics for the neighborhood from the censuses as there is no way to know exactly where all of the people listed were living. But if you can match some names with places, you can trace the route of the census taker.

Under the heading that reads “Names of Heads of Families” you see the Williams and Lawrence households. They were living just north of the current Bronx-Yonkers border by the College of Mount. St. Vincent. If you look further down the list you see the Warners and the Hadleys who lived further to the south in today’s North Riverdale. Down the list you see the Van Cortlandts and the Berrians who lived in Van Cortlandt Park and Spuyten Duyvil. This suggests that the census taker was traveling south along the Albany Post Road from the current Yonkers border stopping at every household until the last entry, “Daniel Halsey,” who operated a tavern at today’s West 230th Street and Broadway. For some reason, William Hadley, who lived in North Riverdale is listed on the previous page.

The column furthest to the right is labeled “Slaves.”

Appendix B:

Primary Source Documents referencing enslaved people at Van Cortlandt Plantation