The Origins of "Mosholu"

Tracking Down the Source of a Mysterious Word

1/18/20 – Nick Dembowski

The Munsee-speaking Native Americans that lived around today’s Kingsbridge had their own names for places in our neighborhood. While these names have largely been forgotten by today’s residents, it would seem that one Munsee name, “Mosholu,” has survived through the centuries and is still used by locals. But a close examination of historical records gives reason to doubt the claims of previous historians regarding the origins of the word “Mosholu.”

The absence of "Mosholu" and prevalence of "Muscoota"

Despite the fact that the Munsee did not leave written records, local Munsee place names were often used in early colonial-era land deeds. The fact that “Mosholu” does not appear in any documents from the early colonial period is therefore a reason to be wonder if it was ever used at all. A geographical feature as prominent as Tibbetts Brook, which frequently served as a property line between estates, would certainly have been named in land deeds–and it was, but it was not referred to as “Mosholu,” but rather as “Muscota Brook” or “Muscota Kill.” A parcel of land next to the Van Cortlandt property is described in 1713 as “butted and bounded . . . Eastward to Musceeto Tippets Brook.”2 Jacobus Van Cortlandt bought acreage in 1722 that was likewise described in a deed as “bounded eastward to Muscoota Brook.”3 There really is no shortage of documentation referring to Tibbetts Brook as “Muscota” or “Muscoota Brook” as these names appear in several additional early colonial land deeds–whereas there are none that use the term “Mosholu.” The surviving portion of a damaged 1684 map of the area labels Tibbetts Brook as “…ota Kill” with the first part of the word ending in “…ota” being lost to damage. Very likely the label originally read “Muscota Kill.”

A Game of Cartographic Telephone

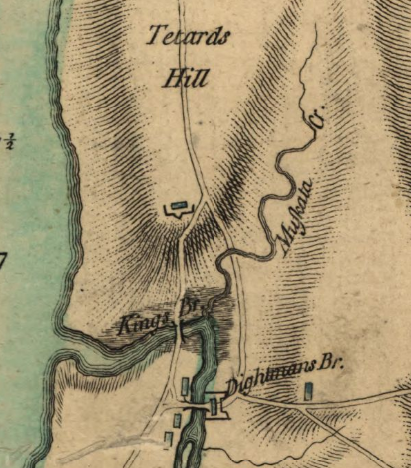

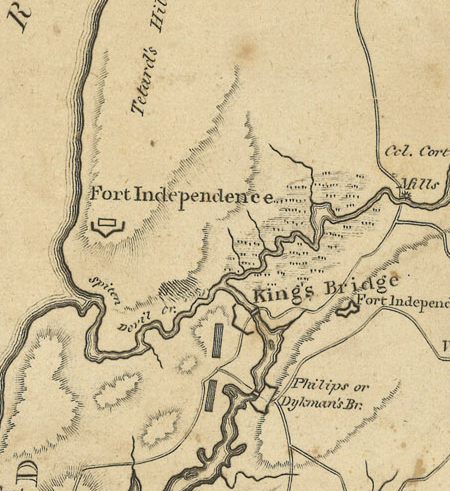

It is not hard to see why Grumet would have reason to doubt Bolton’s theory about “Mosholu.” So where the heck did the word “Mosholu” come from? Could Grumet’s theory be correct–that the word honors a Choctaw chief who fought in the War of 1812? No, because the word “Musholu” appeared 35 years earlier in 1776 on this British map from the American Revolution:

The above map was drawn by Claude Joseph Sauthier, a Frenchman in service of the British during the Revolution. Sauthier was ordered to draw this map “immediately after” the attack on Fort Washington on October 28, 1776.4 Perhaps Sauthier should have been given more time to research the area before drawing the map because it is riddled with errors. The Kings Bridge, Tetards Hill, Miles Square, Valentines Hill, and the Heights of Fordham are all labeling the wrong places. Some of the labels are miles away from where they should be. There are multiple misspellings, too. “Nepperhan” is written as “Wepperham.” “Spuyten Duyvil,” which the British were usually spelling as “Spiten Devil” is instead spelled “Spiling Devil.” An analysis of Sauthier’s maps of New York concluded that they “are essentially works of compilation. They were built on the framework of earlier maps, and corrected or supplemented with new materials, including Sauthier’s own surveys and other maps that came to his attention.”5 Sauthier was copying, or miscopying, labels from other maps as were other British mapmakers. The cartographers that came before him did the same thing–copying from older maps to make new ones. One of the British mapmakers from the Revolutionary period must have copied from a map where Tibbetts Brook is correctly labeled “Muskata Creek” (as in the map to the right) but accidentally mistook the ‘k’ in “Muskata” for an ‘h.’ He also mistook the ‘t’ for an ‘l,’ (just as he did in changing “Spiten” to “Spiling”). Like a game of cartographic telephone, the word “Muscota” becomes “Mosholu” and a new local place name is invented during the American Revolution–well after the Munsee had a strong presence in the West Bronx.

My belief is local 19th century historians living in the Kingsbridge area must have seen the errant Sauthier map, or a map based on it, and mistakenly determined that “Mosholu” was a long forgotten Native American name for Tibbetts Brook. While there is no way to prove this is true, certain facts point in this direction. Not only is the word “Mosholu” nowhere in the historical record before the Sauthier map was published but it also does not appear anywhere after it was published until the middle of the 19th century. At that point in time, the name starts to appear frequently. A local post office at today’s Manhattan College Parkway and Post Road was renamed the Mosholu Post Office. The neighborhood around today’s Broadway became known as Mosholu. A road that traversed Van Cortlandt Park was named Mosholu Parkway. One of the people responsible for the proliferation of the word “Mosholu” was T. Bailey Myers, an early member of the New-York Historical Society along with Robert Bolton. According to a family memoir, “Mr. Myers named the post office nearest his home . . . Mosholu, which name is still retained for the Putnam Railroad station.” Myers lived in the Upper Cortlandt house at today’s W. 238th Street and Waldo Avenue. He also amassed an amazing collection of thousands of original documents and manuscripts from the Revolutionary War–including maps–which were all donated to the New York Public Library. All this is to say that maps like the errant Sauthier map would have been known to the very person who is credited with popularizing the word “Mosholu.”

Interestingly, “Mosholu” is not the only place in the neighborhood whose name is inspired by an errant Revolutionary War map. According to History in Asphalt, Independence Avenue “owes its name to an error. During the Revolutionary War, a British cartographer mistakenly located Fort Independence above Spuyten Duyvil. Nineteenth-century realtors opened a development, and called one of the streets Independence Avenue, and perpetuated the error.”

Based on this other misnamed location, it is clear that locals were looking to British Revolutionary War maps as a source of local place names–making it likely that someone saw the “Mosholu” label on the Sauthier map and just assumed it was a long forgotten Munsee name.

Notes:

- Grumet, Robert. “Indians in the Bronx.” Digging The Bronx Recent Archaeology in the Borough. edited by Allan S. Gilbert, The Bronx County Historical Society, 2018, p. 195.

- Westchester Deeds Liber E p 337.

- Westchester Deeds Liber E p. 338.

- https://oshermaps.org/special-map-exhibits/percy-map/percy-biography

- Allen, David. Comparing 18th-Century Maps of New York State Using Digital Imagery.