Fort No. 2 in The Bronx

An Endangered Relic of the Revolution on Spuyten Duyvil Hill

4/8/19 – Nick Dembowski

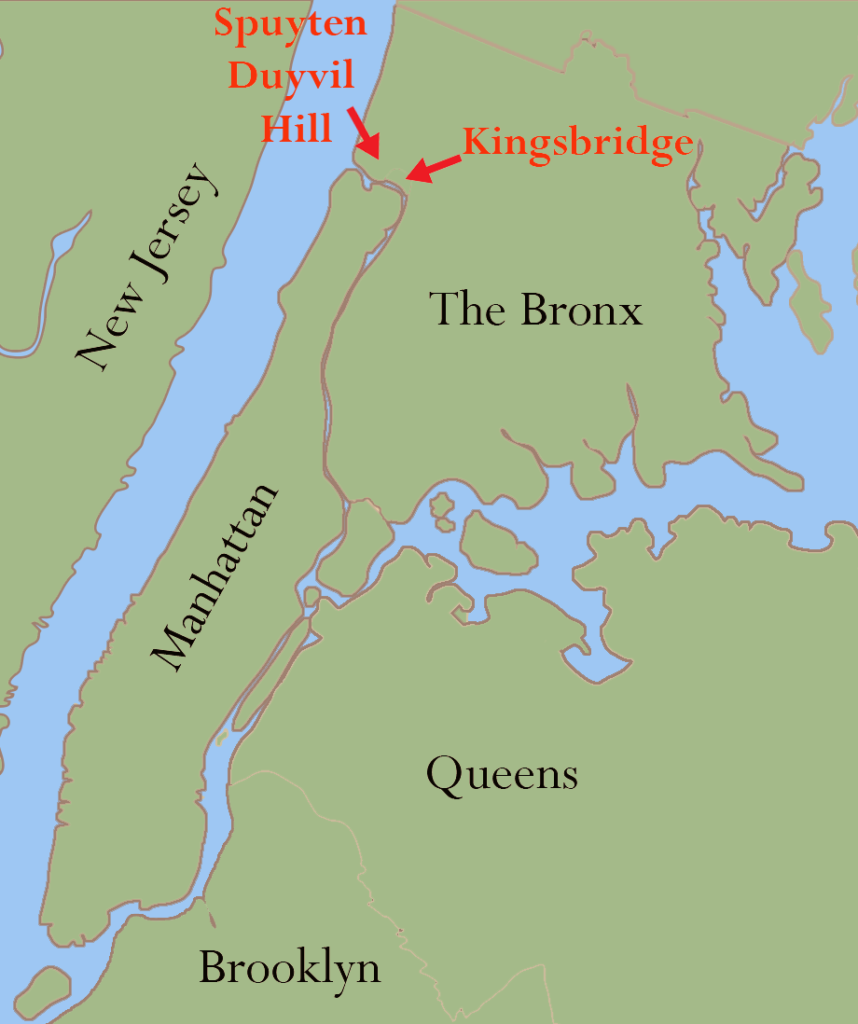

Section of a British map laid over a contemporary satellite photo of Northern Manhattan and The Bronx. A vacant lot on Spuyten Duyvil Hill contains the remains of Fort No. 2 (also called Fort Swartwout). It is located just to the left of the letter “S” in “Spuyten Duyvil” on the satellite photo.

At the end of Fairfield Avenue in The Bronx there is a vacant lot south of West 231st Street. Gnarled vegetation, household trash, poison ivy, and dog poop decorate the lot, which is flanked by single family homes and apartment buildings. Lying below that unattractive veneer is a plot of land that is both important and under imminent threat–a condition as true today as it was 243 years ago. Back then the threat took the form of the British army. Today it is development and a booming market in million-dollar homes. What stands to be lost, beneath the trash and topsoil, is a unique window into New York’s revolutionary past.

At this unassuming and unmarked location are the remains of an old redoubt (or small fort). The area was fortified by Patriot militia in 1776 but fell into British hands shortly thereafter. Uncovering the history of this spot reveals what brought our first president, French nobility, Dutchess County farmers, and Pennsylvania frontiersmen to this part of the City in its most turbulent moment. But it also unveils the thinking of Patriot and British leaders as they struggled with military strategies to capture, defend, and recapture New York City. As the lot is cleared of trees in preparation for development, will the remnants of this fort survive to tell these stories as we approach the 250th anniversary of the Revolution?

Kingsbridge - "A pass of the utmost importance"

After the first battles of the American Revolution outside Boston in April of 1775, a Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia. Among the delegates were all of the big names of the Revolution: Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Washington, and Hancock. While they did not all agree on how to respond to the crisis, they did come together to produce the Resolves of the Continental Congress. This is the first of the resolves:

Resolved, That a Post be immediately taken and fortified at or near King’s Bridge, in the Colony of New-York; that the ground be chosen with a particular view to prevent the communication between the City of New-York and the country[side] from being interrupted by land.1

One could be forgiven for considering this to be a rather random response to events of the day. The British and Patriot armies were still locked in stalemate outside of Boston. Why then was the first order of business to fortify the Kingsbridge area of today’s Bronx (then part of Westchester County)? The Patriot leadership correctly assumed that the British army would soon try to take New York City and its coveted harbor. Home to the only bridges connecting Manhattan to America’s mainland, Kingsbridge would be vital to any defense of the city. Those bridges, the King’s Bridge and the Free Bridge, would keep Manhattan supplied as the superior British navy could easily dominate the waters around the island.

"The great irregularity of the ground"

After the British were driven from Boston in late March of 1776, Washington could turn his attention to the defense of New York City. On June 21, 1776 he wrote to Congress:

I have been up to view the grounds about Kingsbridge and find them to admit of several places well calculated for defence ; and, esteeming it a pass of the utmost importance have ordered [defensive] works to be laid out . . . Their consequence . . . requires the most speedy completion of them.[3]

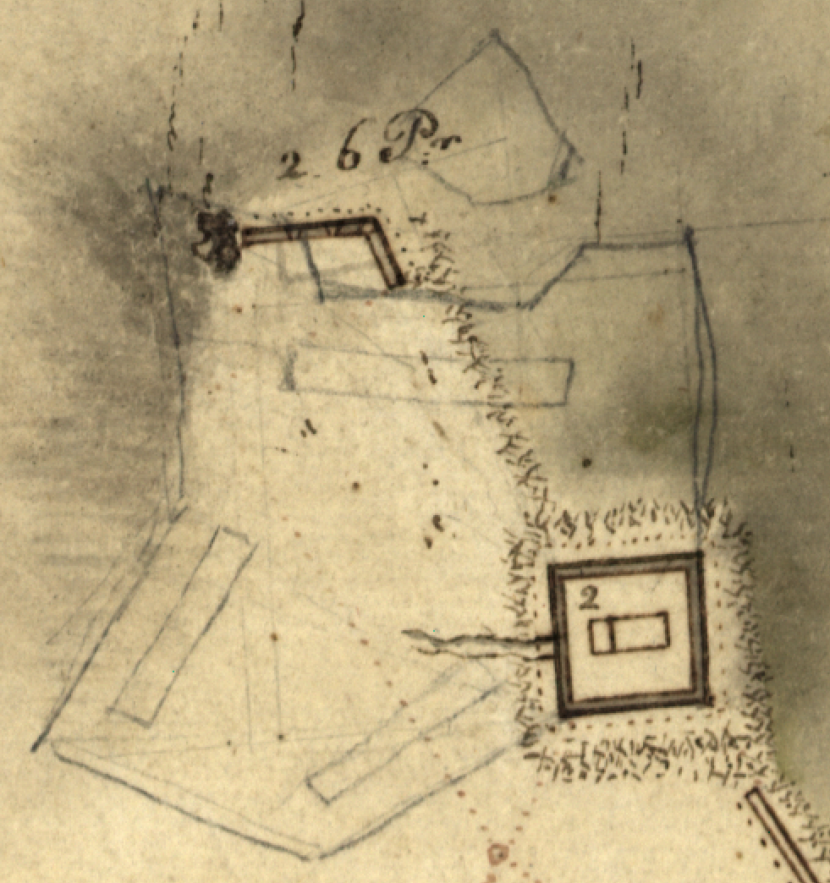

Washington saw what the New Yorkers had seen earlier–that one fort would not be enough to defend Kingsbridge but rather multiple redoubts should be laid out in “several places.” This resulted in the construction of a string of fortifications on the hilltops around the tip of Northern Manhattan. Some had names but they would eventually be best known by the numbers that the British assigned to them. Spuyten Duyvil Hill would eventually host Forts no. 1, 2, and 3. Fort no. 1 was the westernmost, overlooking the Hudson. Fort No. 3 overlooked the strategic King’s Bridge. Fort No. 2 (or Fort Swartwout) sat between Forts No. 1 and 3 on the highest point of ground in Spuyten Duyvil. It was needed to protect both of the other two forts, which would have been vulnerable to attack from the higher ground between them. The remains of Fort No. 2 are what lie beneath the ground of the aforementioned vacant lot, occupying the highest point of land in the vicinity.

The sense of urgency that Washington conveys in his letter to Congress is mirrored in the orders to the Patriot army. The Dutchess County Militia under Colonel Jacobus Swartwout was put to work on fort construction on Spuyten Duyvil Hill. His regiment was ordered: “Its of the utmost importance that the work layd out in this Quarter should be vigorously carr[ied] onto complet[ion] with the utmost Dispatch.” Every soldier “fit for Duty Except a Competent number to Cook and take care of the sick” were ordered to work “Vigorously” on the fortifications.4

To underscore this point for the militiamen, the rum ration was eliminated for “Lazy” workers as the officers’ struggled to motivate and discipline the farmers turned soldiers.5 As they dug ditches and built the walls of the forts on Spuyten Duyvil Hill day after day, the officers’ orders to the men make abundantly clear that this was not a professionally trained regiment. It calls out the troops for plundering local farms, firing their guns for no reason, drunkenness, sleeping while on guard duty, insubordination, pulling down fences, keeping a filthy camp, wasting food, and foul language. This explains why the officers were ordered to “Diligently Superintend the [defensive] works . . . to expedite [them].”6

"To cut off the retreat of many of the enemy"

Underlying the frenzied pace of construction was the concern that the British army would land at Kingsbridge to cut off the Patriots’ supplies and escape route. At this point in the war, The British had amassed a huge army outside the city–the largest British expeditionary force prior to World War I. Where they would attack first was the question that perplexed Patriot leaders. On August 22nd, the British began landing on Long Island and the disastrous Battle of Long Island would soon doom the Patriot defense of the city. But even as the British disembarked on Long Island, Washington could not be sure that it was not a diversion, with the main attack coming elsewhere. On the very day of the Battle of Long Island, the Patriots received intelligence that the British would land up the Hudson River. This compelled Washington to keep thousands of troops busily fortifying the hills at Kingsbridge when they could have been more useful fighting the British on Long Island.

The decision of where the main attack would happen came down to William Howe, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the British army in America. And, in fact, his initial plan called for sending a “respectable detachment” above Kingsbridge to force a decisive battle.7 But as the day of battle approached, his strategy shifted and he ordered his army to Long Island instead.8 His second-in-command, a tactical mastermind named Sir Henry Clinton, urged Howe to reconsider Kingsbridge as the wiser target. Clinton wrote after the war that he proposed “to the Commander in Chief the landing of a sufficient corps at Spuyten Duyvil in order to lay hold of the strong eminence adjoining, [that is Spuyten Duyvil Hill] for the purpose of commanding the important pass of Kings Bridge.” He reckoned that such a move “might also, with the assistance of our armed vessels, have possibly put it in our power to cut off the retreat of many of the enemy.”9 Here Clinton echoes a common criticism of Howe: that in New York he squandered the best chance he had of winning the war in a decisive battle–adding that seizing Spuyten Duyvil Hill could have been the key to that elusive victory.

Patriot forces were trounced on Long Island but pulled off a skillful escape to Manhattan. Even after the battle, the Patriots feared being cut off at Kingsbridge and work continued on the Kingsbridge forts.10 The British would fight the Patriots on Manhattan–driving them further north–as the bulk of the Patriot army would flee over the King’s Bridge and into Westchester County. Washington had indeed escaped into open country as Sir Henry Clinton feared, and from then on, surviving to fight another day became the modus operandi of the Continental Army–a way of fighting that gradually exhausted the British.

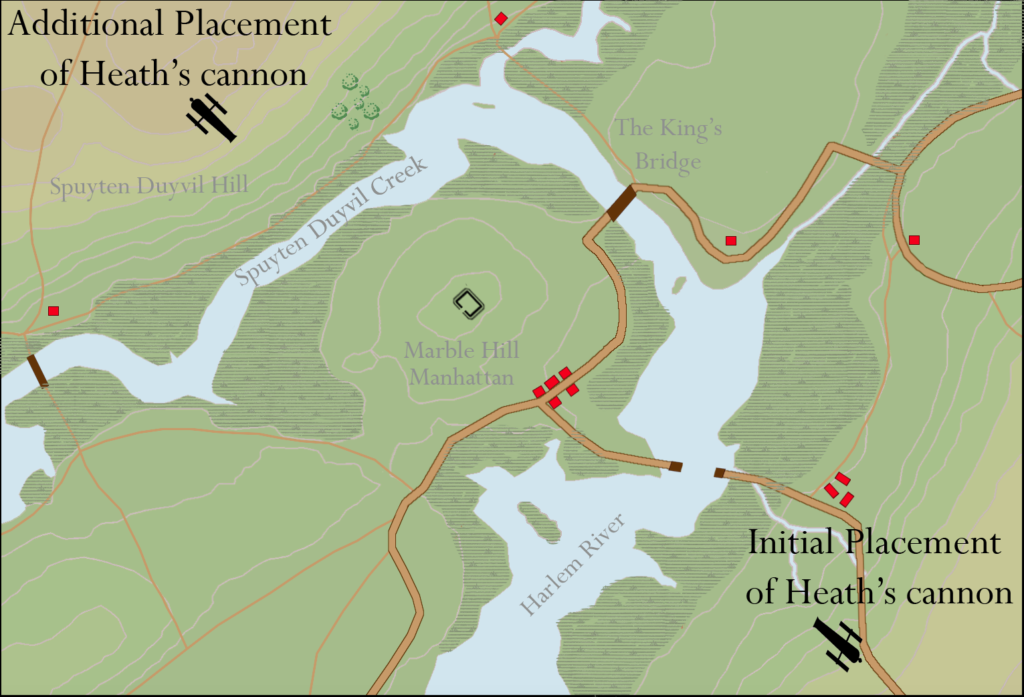

The Patriot's Fort Swartwout becomes British Fort No. 2

The British victory in the New York campaign of 1776 ensured that they would have a base of operations on Manhattan. This left them in a position that Washington had occupied earlier–requiring a strategy to defend New York City. However, having both the port of New York and a large navy, they did not depend on the King’s Bridge for supply. Perhaps for that that reason, the British did not initially garrison Spuyten Duyvil Hill to defend the King’s Bridge. Seizing upon this lapse, Washington ordered three divisions under Major-General William Heath to Kingsbridge in early 1777. Heath mounted his cannons up the East bank of the Harlem River and fired on the British forces on Marble Hill. This compelled the British to seek shelter on the other side Marble Hill and in their fortifications. In response, Heath ordered a cannon “hauled up to Tippit’s Hill [Spuyten Duyvil Hill] and the enemy were cannonaded both in front and in rear : they were thrown into the utmost confusion.”11 Unfortunately for Heath, and to the embarrassment of Washington, Heath’s division was unable to summon ammunition for his siege artillery so he could never truly threaten British fortifications on Marble Hill.12 With the King’s Bridge pulled up (it was now a drawbridge) and the Harlem River acting as a moat, Heath saw no way forward. Facing bad weather he withdrew his army.

But Heath’s attack exposed a threat to the pass at Kingsbridge emanating from Spuyten Duyvil Hill. Before the Patriots could attempt another attack on Kingsbridge, the British rebuilt and garrisoned the hilltop forts.14 The British defense of northern Manhattan was primarily handled by Loyalist militia and German allies. For a time in 1778, a German Lieutenant named John Charles Phillip Von Krafft was stationed at Fort No. 2–lodging “in the little huts . . . near the redoubt.” His detachment was to mount a watch at forts No. 2 and 3. During his time there, he would write about the hardships and depredations of the war. Troops were deserting “in large numbers on account of bad camp (just like ours) and poor rations, namely (like the whole army) scarcely 5 lbs of bread in 7 days and for 2 days rice instead of bread. How often . . . the pieces had to be cut thin!”15 His journal describes a near death fall into the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, and numerous deadly skirmishes with “the Rebels” in today’s Bronx and Westchester.

As troops were required in different parts of North America, the British abandoned Fort No. 2 and withdrew their defenses at Kingsbridge to the Manhattan side of the Harlem River. Many of the outer defenses were dismantled by the British for materials.16 Such was the situation of the fort in 1781, when Washington’s army finally managed to link up with the French army of General Rochambeau. In the years after his humiliating defeat in the New York campaign of 1776, Washington had been smarting for a chance to redeem himself in the city. His plans always seemed to take him back to Kingsbridge as again, lacking a strong navy, he had few other options for an attack on Manhattan.17 With the professional French army and artillerists at his side, Washington planned attacks on New York that might draw out the British and give him a foothold on Manhattan but bad weather, bad roads, and a lack of coordination always seemed to get in the way. While serious encounters involving thousands of troops did occur in the neighborhood, the British could always flee back to Manhattan and pull up the drawbridge of the King’s Bridge leaving the Patriots and French without an enemy to pursue.18 However, with the British on the other side of the river, Washington and Rochambeau took advantage of the situation. Over the course of weeks, the generals gathered valuable intelligence of British deployments and fortifications during, what would be termed, the “Grand Reconnaissance.”

This mission brought Washington and Rochambeau to Spuyten Duyvil Hill on multiple occasions as it provided a vista of British fortifications on Manhattan. There can be little doubt that the generals would have made observations from the site of Fort No. 2 as it occupied the highest point on the hill. Washington’s diary entry for July 22, 1781 shows his discovery of what Heath had found . “I began with General Rochambeau to reconnoitre the enemy’s position and [defenses] ; and first from [Spuyten Duyvil] Hill . . . From thence it was evident, that the small redoubt [on Marble Hill] would be absolutely at the command of a battery, which might be erected thereon.”

However, before long, news of the French fleet’s impending arrival at the Chesapeake Bay would come and Washington abandoned his plans for New York City. The Franco-American force departed to do battle at Yorktown, where a decisive victory crushed British hopes for regaining its colonies. After the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, perhaps the heights of Spuyten Duyvil Hill provided locals with a view of the victorious Washington crossing the King’s Bridge to reclaim Manhattan on November 25th–a day that would become known as Evacuation Day and celebrated for more than a century.

Locating Fort No. 2

Before the turn of the 20th century, the ruins of the old forts were clearly visible on the surface. In 1910 local historians including Reginald Pelham Bolton of the New York Historical Society investigated the site of Fort No. 2, and they discovered numerous artifacts despite a cursory inspection. They described its location precisely, placing it on the site of today’s vacant lot.19

Not long after Bolton’s discoveries on the fort site, the land became the property of a local country club. It featured a club house but no buildings were ever constructed on the high ground previously occupied by the fort. A tennis court was put on the high ground but that, in all likelihood, acted to preserve the ruins of the fort below. The clubhouse burned down and in the decades that followed, this swath of undeveloped land shrank as new private homes were built closer and closer to the fort site.

In the late 80’s an archaeological team, including Professor Allan Gilbert, studied the ground using remote soundings.20 Due to erosion, soil does not typically accumulate at the high point of a rocky hill but soil resistivity testing revealed an unusually large amount of fill on top of the bedrock. “I find that peculiar ” says Professor Gilbert, “I think that it is a worthy location to just have a look to see whether we can, in fact, find intact aspects of the earthwork walls.”

Unfortunate Developments

New York City is not a city preoccupied with the past. Unlike other east coast cities like Boston and Philadelphia, it does not have an “old town”. Plowing over the old and building the new is too hard to resist considering the profits involved. Just recently, the plot containing the fort’s remains was sold to a developer with plans to build three custom homes on the site. Trees have been partially cleared and the ground awaits the bulldozer. But so very little remains from the Revolutionary period in this city despite the fact that all five boroughs played a role in the struggle. Fort No. 2 hosted common people, our future first president, and European nobles. Yet this diverse cast of characters pales in comparison to the mix found on Spuyten Duyvil Hill today. I know because I worked for many years as a 4th grade teacher at The Spuyten Duyvil School, the public school just blocks away from the vacant lot. I taught students whose families were from Korea, Pakistan, The Dominican Republic, Albania, Mexico, Israel, Serbia, Russia, as well as the nearest public housing project. As they learned about the American Revolution, nothing fostered a greater connection to the drama of the past than our field trip to this vacant lot, where we read the journal entries of the people from the past who stood the same ground. There is nothing to mark the place so none of the students nor their parents knew this history, despite the fact that some lived in the apartment building in the adjacent lot.

And that is the point. It is not to prevent these homes from being built. After all, Spuyten Duyvil’s single family homes give the neighborhood its character. The point is that the developer should let a team of local historians and archeologists onto the site before construction begins to study and document what remains of the fort and perhaps save some artifacts from the dumpster. In fact, there is a team ready to go should they be given permission. The community would learn about its past and historians would not have to wonder about what could have been. Then construction could proceed as planned. It would be a welcome relief from the tired narrative of historians and developers grinding it out in the press.

Let a team of local historians and archaeologists onto the site before construction begins to study and document what remains

But as developers and foreign investors continue to fuel the City’s market for multimillion dollar homes, the loss of this site could soon be a done deal. At a time when the colors of New York’s electoral map reveal stark divisions between places like The Bronx and rural Dutchess County–home of the militiamen who built the fort, I can’t help but feel that we are missing an opportunity in the lead up to the 250th anniversary of the nation’s independence. This place in The Bronx helped classes of first-generation American school children consider the convictions of those Dutchess County farmers. The question is: can this piece of history can be studied before it is lost or will it instead teach a familiar lesson about the value of our history weighed against profits?

UPDATE: I have written an addendum to this article – Georeferencing Spuyten Duyvil’s Hilltop Forts

UPDATE 2: Construction has begun. Update here: https://kingsbridgehistoricalsociety.org/forums/topic/site-of-revolutionary-fort-no-2-lost-to-history/

Notes and references:

1 – Force, Peter. American Archives: Fourth Series Vol. 2. M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1839. Washington. p. 1259.

2 – Force, Peter. American Archives p. 1278.

3 – George Washington to Congress, 20 June 1776.

4 – Order Book of Col. Swartwout’s Dutchess County Regiment of Militia, New York Historical Society. p. 46.

5 – Swartwout Order Book, p. 46.

6 – Ibid. p. 49, 63, 68, 89, 95, 139.

7 – Gruber, Ira D. The Howe Brothers & the American Revolution. Athenum, 1972. New York. p. 104-106.

8 – There is not much documentary evidence to explain why Howe changed his mind. Unlike Washington, he did not keep copious notes. It is possible that intelligence gathered from British ships on the Hudson, such as the Phoenix and the Rose, convinced him that the Patriot force at Kingsbridge was too strong for an assault. Or perhaps, as Gruber asserts, Howe’s overall strategy became more focused on capturing and holding cities as opposed to defeating the Patriot army.

9 – Clinton, Sir Henry. The American Rebellion. Yale University Press, 1954. New Haven. p. 40.

10 – George Washington to Congress, 6 September 1776.

11 – Heath, William. Memoirs of Major-General Heath. I. Thomas and E.T. Andrews, 1798. Boston. p. 110.

12 – George Washington to William Heath, 3 February 1777.

13 – George Washington to William Heath, 6 January 1777 and George Washington to William Heath, 17 January 1777.

14 – Orderly Book of the King’s American Regiment, 17 July 1777. University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library.

15 – Von Krafft, Lt. John Charles Philip. Journal of Lt. John Charles Philip Von Krafft. Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the year 1882. New-York Historical Society Publication Fund, 1883. New York. p. 69-70.

16 – Von Krafft Journal, p. 93.

17 – Washington ordered Heath’s attack at Kingsbridge in 1777. Washington’s plans for 1778 also contemplated an attack at Kingsbridge. When he believed that the French fleet might assist him in New York in 1779, he thought up a multi-pronged attack involving French ships at Kingsbridge. In 1780, he proposed the idea of a surprise attack on the “Posts at Kings-Bridge” to his generals. In 1781, he tried to convince the French General Rochambeau to attack New York, which brought their combined armies to Kingsbridge. While many of these plans never came to fruition, the area around Kingsbridge was the scene of nearly constant guerilla warfare between soldiers and partisans of both armies. It would be quite an undertaking to document all of the raids, skirmishes, and ambushes recorded in the diaries of soldiers stationed around Kingsbridge.

18 – As was the case on July 3, 1781 and July 21, 1781.

19 – Bolton, Reginald Pelham. Relics of the Revolution. Published by Reginald Pelham Bolton, 1916. New York. p. 203.

20 – The team included archaeologist Valerie De Carlo, Professors Roger Wines and Allan Gilbert of Fordham University, KHS member Joe Hussey, and Kingsbridge Historical Society president, Peter Ostrander, who organized the site visit.