Georeferencing Spuyten Duyvil's Hilltop Forts

Earlier, I published an article about the imminent development of a vacant lot, where Fort No. 2 once stood. If the hilltop forts of Spuyten Duyvil are not already familiar to you, I would recommend you read that first. However, for those skeptical of Fort No. 2’s historical footprint (or for those that just want to learn more) I thought it would be worth demonstrating how maps can be georeferenced to definitely locate the former Fort No. 2 on that vacant lot. Georeferencing is the process of aligning, scaling, and orienting maps or diagrams to one another.

Today the location of the vacant lot where Fort No. 2 once stood can be described using streets, block and lot numbers, or GPS coordinates as reference points. But during the Revolution, and for many years after, none of these descriptors existed. But what did exist were the remnants of the forts themselves. And local historians of the 19th century could see them and describe their location in relation to local landmarks. By using the notes of these early historians alongside modern maps, and a British engineering diagram, those landmarks can be used to pinpoint the modern day locations of Spuyten Duyvil’s hilltop forts–including Fort No. 2.

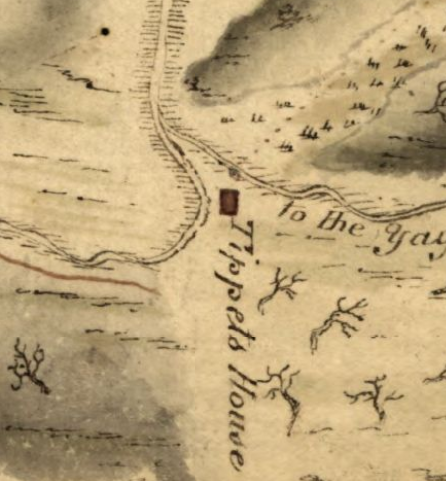

"A Plan of the Works on Spikendevil Hill"

The British engineering diagram comes courtesy of the Library of Congress. The key to understanding maps from the Revolution is to know why they were made. This one was clearly drawn for the purpose of showing the features, dimensions, and relative position of the 3 Spuyten Duyvil hilltop forts. It is entitled “A Plan of the Works on Spikendevil Hill with the Ground in front Protracted from a Scale of 200 Feet to an Inch.” While many other maps exist that depict the hilltop forts, this one offers the most precision as it is “zoomed in” on the forts themselves.

Fort No. 1

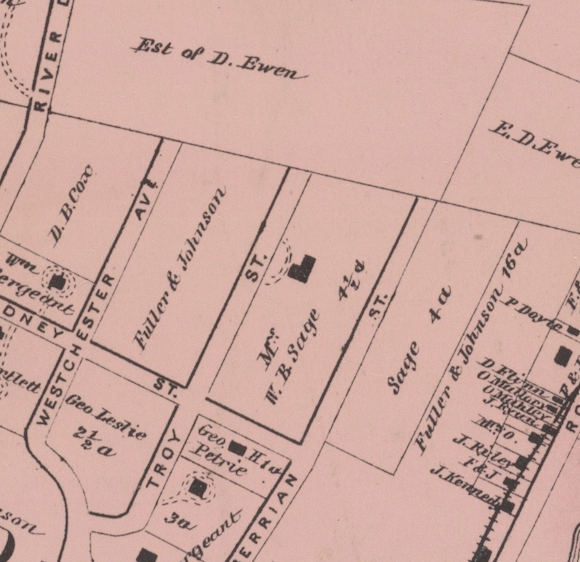

Comparing the 1872 Beers map to a contemporary Google map, it is clear that Washington Street follows the path of today’s Kappock Street while Independence Ave of 1872 roughly follows Independence Ave of today. Henry Hudson Park would have been to the south of the Strang mansion.

So the location of Fort No. 1 is clear but in order to properly orient the 1778 British engineer’s map to a contemporary one, at least two reference points are needed. Even more can be helpful to confirm the orientation. Our second reference point will be the easternmost fort–Fort No. 3.

Fort No. 3

Since several of the homes around the inn are still standing, it becomes possible to precisely find the location of the inn and thereby know the location of Fort No. 1:

Georeferencing the British Map

With the locations of Forts No. 1 and 3 known, it now becomes possible to georeference the 1778 British map to a contemporary one. The process is depicted in the below animation. You will need to pause over the image and let it cycle through to get the full effect.

What is remarkable about the process is that after properly orienting the engineer’s map and bringing it to scale, the results match the historical record exactly. Both Forts No. 1 & 3 are where they should be. Perhaps this is not a surprise given the precision and detail apparent in the British map. But is there anything else on the map that could verify our results? Yes, and it comes thanks to a seemingly insignificant detail.

"Tippet's House"

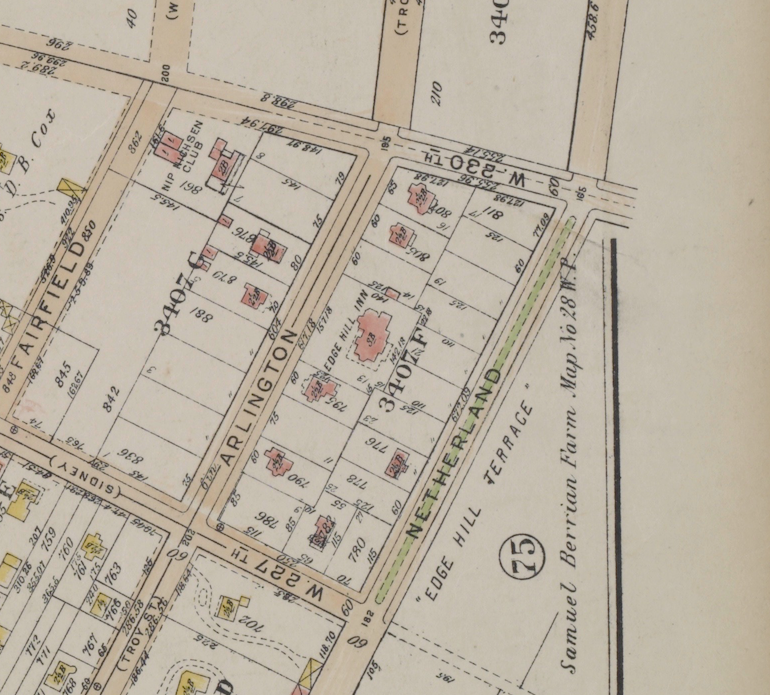

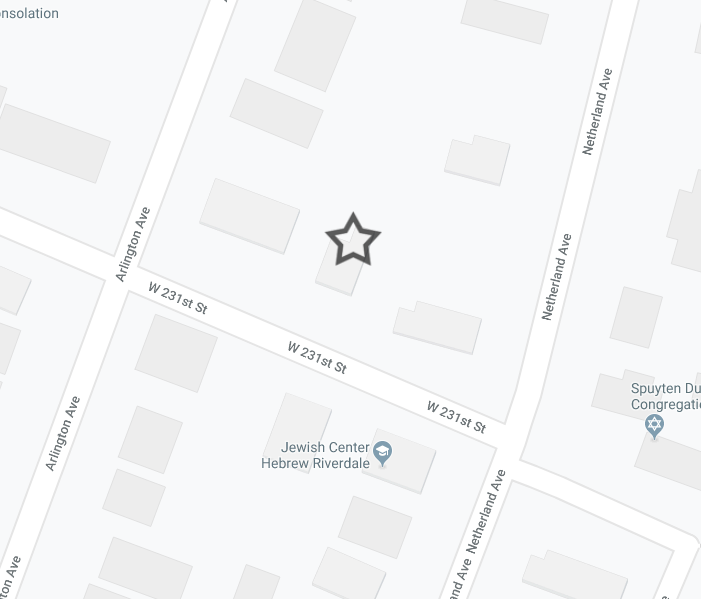

For some reason, the British map maker saw fit to depict the Tippett residence in this diagram. According to the results of our georeferencing, this house should have been located on the north side of West 231st Street between Arlington and Netherland Avenues, where today there is a home.

That archaeological dig and the results of the auction are detailed in this clipping from the New York Daily Herald to the right. Remarkably, one of the Tippett descendants phoned in to buy the lots containing the historic homesite, which were revealed to be lots 91 and 92 of the auction. The Ewen estate sale auction map reveals that these lots were indeed on the north side of W. 231st Street between Arlington and Netherland Avenues–confirming the historical location of the Tippett house was exactly where the georeferenced map showed it to be. So the position, orientation, and scale of the georeferenced maps are spot on!

Fort No. 2

Knowing that the map and satellite image are accurately georeferenced, we can now trust them to show the true location of Fort No. 2, which is confirmed to be the vacant lot that is to be imminently developed at Fairfield Avenue and W. 230th Street.

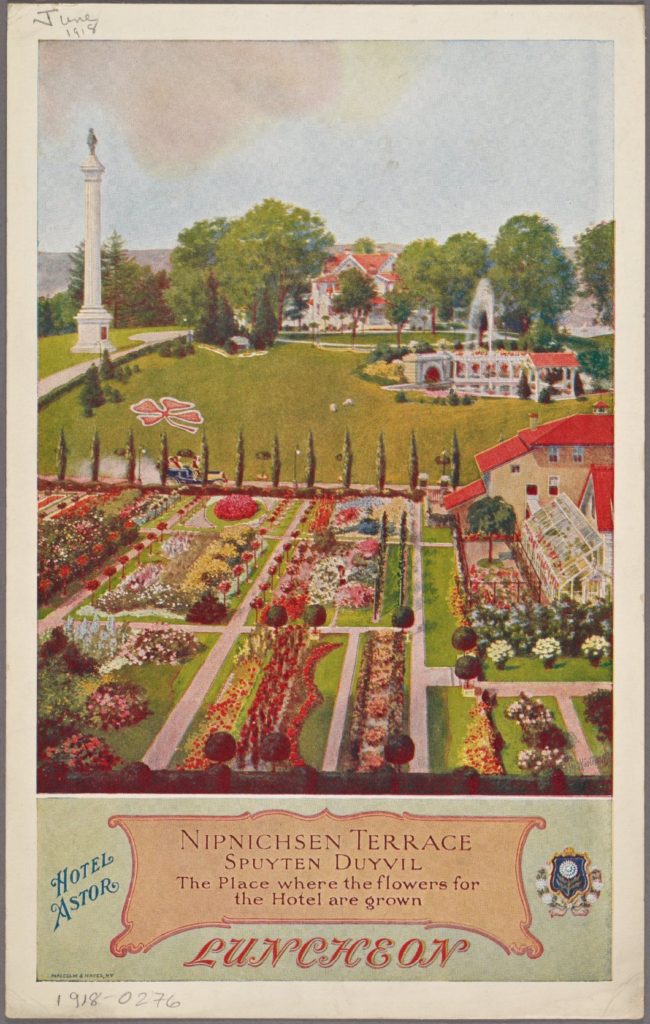

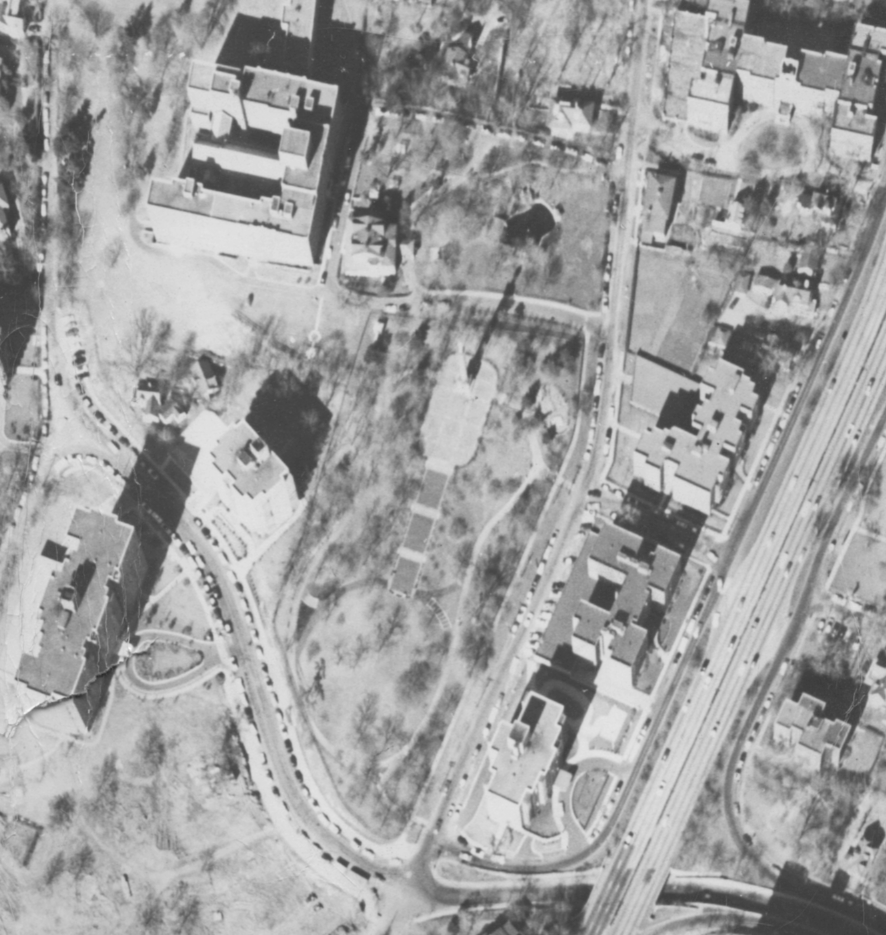

The results of our georeferenced maps show the footprint of the fort on the left. On the right, is a 20th century aerial photo that depicts the same area. It is hard not to notice that the orientation of the fort mirrors the orientation of the old Nipnichsen Club tennis courts that were built upon its foundation. That rectangular piece of land is the highest point of ground in this part of Spuyten Duyvil. It is perfectly logical that a military engineer would want to construct the fort on this piece of high ground just as it is logical that a level and squared off area would be a good place to put a tennis court.

The precise British diagram, the historical record, satellite imagery, and modern technology confirm what local historians have known for years–the historical footprint of Revolutionary Fort No. 2 is located in the vacant lot where Fairfield Avenue meets W. 230th Street. The outline is still visible . . . but likely not for long.

Notes and References:

1 – Edsall, Thomas H. History of the Town of Kings Bridge. Privately Printed, 1887. p. 29.

2 – Jenkins, Stephen. The Story of The Bronx. G. P. Putnam’s and Sons, 1912. p. 126.

3 – ibid.

4 – ibid, p. 329.

5 – Edsall, Thomas H. History of the Town of Kings Bridge. Privately Printed, 1887. p. 30.

6 – Bolton, Reginald Pelham. A Pioneer Settler’s Home on Spuyten Duyvil Hill. The New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin, Vol. V., No. 1, April, 1921. p. 13-18.