Home › Forums › The Industrial Era › On this date in 1886 – A Walking Tour of Riverdale, Kingsbridge, Spuyten Duyvil

- This topic has 1 reply, 2 voices, and was last updated 3 years, 6 months ago by

Thomas Casey.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

October 8, 2020 at 7:40 pm #1658

This article appeared in the October 8, 1886 edition of the Evening Post and captures the joy of autumn walks. It contains oodles of fascinating information and I would not suggest starting it unless you are in a comfortable chair! I was very tempted to annotate it as there are so many interesting references but that would take a very long time. So, for now, I am just presenting the straight transcription below and encourage you to ask questions about anything in the article:

A Tour Around New York

An Unexplored Region–Traces of Cowboys and Hessians–Lords of the Manor–Through a Glass Darkly–Old Homes and Haunts.

“Felix,” said my grandmother, pausing in her knitting, and pushing her spectacles up until they found a resting-place in the thick bands of her silvery hair–for the dear old lady wore caps only on gala days and occasions of ceremony–”Felix, I don’t want to see you make a holiday time of Sunday. My little brother Oscar went up to Spuyten Duyvil Creek and Tippett’s Brook on Sunday, and was upset and nearly drowned, and my mother, I remember, kept him on catnip-tea diet for a week afterwards. It’s unlucky, Felix. Do you remember Oscar? Oh, no, of course not. Let me see: how many years ago is it since Oscar went to see such a brave, strong lad, and never was heard of again! Mother never gave him up, and when she lay dying–long before you were born–she raised her head as the door opened suddenly, and asked if that was Oscar. Poor boy, he had been dead for twenty years, I suppose. Well, it doesn’t signify. In another hour she had met him and found out why he never came home to her, and I shall know all about it soon.” And the old lady dropped her hands in her lap, and her ball of yarn rolled to her feet and started the cat in pursuit of it, while her wistful eyes, always bright in defiance of advancing years, lost sight of all surroundings and seemed to pierce the veil that so long had hidden the playmate of her childhood.

This scene and my grandmother’s words of warning against Sunday indulgence in pleasure travel–an old-time prejudice which the world seems to have outlived–came back to me last Sunday as I was whirled in the railway cars along the banks of Spuyten Duyvil Creek, to the vicinity of the spot where Anthony the Trumpeter and my great-uncle had alike come to grief. It was an extra day in the “Tour,” for, with the advent of a red tinge to the maple leaves, and the purpling of the oak tops, and with the opening of the reign of golden rod and gentian and aster, there had come an irresistible desire to explore the terra incognita of New York, the land lying north of Kingsbridge, known little to the denizens of this big city, excepting real-estate speculators and antiquarians. It is a land of stately old homes and luxurious modern residences; of the forest primeval and the landscape gardener’s effects; of aesthetic interiors and of old-fashioned window seats, in which Continental soldier and Hessian hireling alternately lounged; of lake and creek, and highland and meadow; of mounted policemen and letter-boxes and steam fire engines; of fields and hills that have not changed their contour since Peter Stuyvesant’s solid men at arms marched over them, and King George allotted their fertile acres to his liege subjects. It is a land, too, that lies within the city limits, and I, Felix Oldboy, wearied of beholding only that which modern hands had improved out of all recollection, yearned for a leisure Sunday under oaks and chestnuts in city woods, which should recall the days of fishing in “Sunfish Pond” on Beekman Hill, and of gathering autumn leaves on the Bloomingdale Road, that used to stretch from Union Square to Kingsbridge in an unbroken panorama of rural loveliness.

There is nothing more beautiful in the way of landscape that that which greets the eye where Spuyten Duyvil Creek joins its waters to the Hudson–the lake-like rivers overlooked by wooded heights on either side, while beyond the Palisades rise abruptly in their grandeur, and distant hills to the east complete a picture worthy of the pencil of Claude. At Kingsbridge, too, there is much pastoral loveliness, the silver threat of Tippett’s Brook (Mosholu, in the Indian tongue) wanders up through the vale of Yonkers, with frowning ridges on one side, and on the other, meadows and orchards over which hills crowned with the green of ancient forest trees stand sentinel. One can walk in almost any direction and soon be able to fancy himself living in the times of long ago, or anywhere else save within the municipal boundaries of the chief city of the New World. It is fortunate for future generations that much of this landscape loveliness is to be preserved in the new Van Cortlandt Park, which will be about two miles in length and one mile broad. The land to be taken affords every variety of landscape, and its natural features render it a far more desirable acquisition than Central Park. Originally part of the Van Cortlandts in 1699, when the head of that house married Eva Philipse, daughter of the Patroon. Time has brought few changes to these lands since the days of the Revolution, when Augustus Van Cortlandt, then Clerk of the Common Council, buried the city archives in a cellar built in his garden for that purpose, to save them from destruction by the British.

After these grounds pass into possession of our city authorities, it is hoped they will return the favor in kind, and preserve from destruction the old Van Cortlandt mansion-house. It is a large edifice of stone, unpretentious in its way, and yet possessing a stateliness of its own that grows up on the visitor. Erected in 1748–the date is on its front–it preserves within and without many of the peculiarities of the last century. One of the rooms in especial is unchanged since the time when the Hessian commandant of the Green Yagers occupied it and General Washington made it his headquarters just before his triumphal entry into New York on Evacuation Day, 1783. Around the fireplace are old-fashioned blue tiles that tell Scriptural stories in the quaint method of illustration then prevailing, where saint and sinner were alike, as my grandmother would say, “a sight to behold.” The deep window seats are admirably suggestive of a quiet smoke for the elders and cosey flirtations for the yonder people. Andirons, which have a history of their own, speak comfortable words of the day as backlogs and plenteous brushwood. As for the furniture, it is again in fashion and most valuable, for it is genuine in its antiquity, Jarvis, Copley, Stewart, and Chapman have furnished the family portraits, one of which is that of a knighted Vice Admiral of the British Navy.

But thereby hangs a tale. Outside, above the old-fashioned windows, are some exceedingly grim visages carved in stone in the shape of corbels, whose serious, not to say morose, aspect would be calculated to drive away any sensitive turnip in affright. Pointing up to them, my quondam schoolmate, Bowie Dash, who occupies an ideal cottage embowered by the trees that fringe the ridge, through which Riverdale Avenue sweeps, remarked: “Those are the portraits of the Van Cortlandt ancestors–family portraits all of them.” “Yes,” said Mr. Van Cortlandt with all seriousness, “and that particularly solemn one yonder was carved after he had been out all night with the boys.”

The windows themselves present an interesting scientific problem. Upon two sides of the house the glass has all the appearance of ground glass, though it were perfectly transparent when first placed there. Closer examination reveals a process of disintegration, spicula of glass falling off when scraped by the finger-nails. Amateur scientists have been unable to account for it. Exposure to the salt water of Mosholu Creek would be a plausible theory if all the glass fared alike. But some years ago the rows of stately box, venerable for their height and antiquity, which stood in the old garden and faced the windows that exhibit this phenomenon were cut down, and the glass that has been inserted since that time shows no sign of change or decay. Whether the combination of box scents and salt air will account for the problem, is a matter which only experimental science can determine, and Mr. Van Cortlandt would be very glad to have the puzzle solved.

There is scarcely a foot of ground about Kingsbridge that is not historical. Here the British had their outposts in the Revolution. Both sides erected earthworks on the adjacent hills. Skirmishes were frequent in these meadows, and many lives were sacrificed. Relics of the war–cannon-balls, bayonets, skeletons in full uniform–have been turned up by spade and plough, and many more are awaiting their resurrection at the hands of public improvements. The old tavern at Kingsbridge saw lively times in peace as well as war. The Albany post-road passed its door, and teams and passengers baited here. Dainty dames in lofty headgear and ample hoops have danced with the sons of the patroons on its floors, and smugglers have made it their headquarters for lawless forays. Going, going, gone. The public surveyor and the moder apartment-house are in hot pursuit of these romantic old localities, One has only to turn into Riverdale Avenue to be aware that the luxurious civilization of the period is learning to appreciate the beauties of this neighborhood, which, when I was a boy, was associated with the names of Lispenard Stewart, Abraham Schemerhorn, Ackerman, Delafield, Wetmore, and Whiting.

It will be a pity to blot out the natural beauties of the spot for the sake of a little more brick and mortar–at least I thought so last Sunday as I climbed up Riverdale Avenue and fancied myself temporarily in Elysium. Riding is too rapid a gait to allow of realizing the beauty of forest, ravine, meadow, hillside, brook, and homes enshrined in landscape loveliness which is presented to the pedestrian on either side of the road. Tired! Not a bit of it, even if I am growing stout, and this is considerable of a hill to climb. I am looking at that maple. Did you ever see such a splendor of crimson and gold as lights up its top and sides! That fringed gentian–are not its purple spikes a delectable contrast to the sunny cluster of its taller neighbor, the golden rod? The oak leaves are turning ruddy, too, as if they had been imbibing freely of the autumn’s product. These old fellows have a right to be jolly too, for they were children at the time when Hendrick Hudson’s Halve Maan anchored in Spuyten Duyvil Creek, and shot a falcon at two hundred Indians who had gathered on shore to dispute the right of way, and dispersed them with the noise and execution of this terrible weapon.

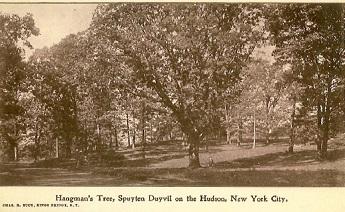

There is one oak still standing in a little wood that has known no change for a century, which has a history of its own. It is a sturdy tree with ample brown arms, clad to-day in a royal robe of purple, and defiant seemingly of all changes except such as the iconoclastic axe of the woodman may bring. You can see it from the road. Under its branches, so my informant tells me, a horse that bore a good soldier of the Union all through the late war, and whose gray coat is still presentable, is grazing peacefully. But in other days these great gnarled limbs bore other fruit. Tradition affirms that during the war of the Revolution more than thirty cowboys were hanged from this oak, and the annals of those days bears out the popular legend. This part of the “neutral ground” of ‘76–a territory extending from Harlem River to the Croton, and which was ravaged with engaging impartiality by the camp-followers of both armies. The British called themselves irregulars, but the name “cowboys” could not be wiped out, and their punishment was never irregular when they were caught. The gentlemen who did the same favor to the Continental flag were called “skinners,” and their schrift was an equally short one when caught. Usually the latter had the best of the game, because the sympathies of all except the large landed proprietors were with the colonies.

Beyond the wild primeval wood that holds this historic oak stands what seems to me, for the situation and surroundings, the most beautiful home in the city. A stately stone mansion, half covered with vines and encircled by thirteen majestic elms, stands on a knoll which overlooks the Mosholu Valley and gives glimpses of twenty miles away. Nature did nearly all that was possible for its seventeen acres, and the landscape gardener has finished it. At one side all is wildly picturesque, with ravine and brook and masses of rock: on the other civilization has done its best and equally admirably. On an apple tree still standing Jacobus Van Cortlandt carved his name nearly two centuries ago, and the stout stone farm-house that another Van Cortlandt built in 1766 shelters the coachman’s family. The place is now owned by Mr. Waldo Hutchins, who has been living there for the past twenty years.

Broad piazzas, a hall of ample width that shows no sign of a stairway, great rooms with high ceilings, thick walls, and large windows, recall the old baronial homes of Virginia. But there the resemblance ceases, save in the matter of baronial hospitality, for modern luxury clothes the interior or more royally than our ancestors dreamed of–and, it must be confess, more comfortably. Of the family heir-looms within, two portraits taken from life interested me most. One is of Noah Webster–the maternal grandfather of Mrs. Hutchins–the patient, industrious builder of the dictionary, who wrought at his work for twenty years, until his fingers became stiff from using the pen and he fainted away when he had written the word “Finis.” No wonder. I held some of his manuscript in my hand, and it was so suggestive of hard work. The other portrait presents Oliver Ellsworth, the paternal grandfather of Mrs. Hutchins, in his robe of Chief Justice of the United States, only with the addition of a red velvet collar to set off the sombreness of the heavy folds of black silk. His is a typical New England face, intellectual, determined, and strong. A later generation has forgotten that after the “Virginia plan” had been adopted by the Constitutional Convention of 1787, on the basis of a “national Government,” or a single republic, in contradistinction to a Federal Union of separate States, on motion of Mr. Ellsworth the word “national” was stricken out and the words “Government of the United States” substituted in its place. The Connecticut statesman led the State-rights column in those days, as in these Senator Edmunds of Vermont seems to be its most stalwart leader.

Riverdale Avenue forms a beautiful drive. Its roadway is as smooth as any drive in Central Park, and it has every advantage in the way of scenery. But this holds good only up to the city line, beyond which point the Yonkers authorities seem to look upon it as a country road, and treat it accordingly. The castellated mansion which Edwin Forrest built, and which he named Font Hill, marks the end of the city limits. It long ago passed into the hands of a religious sisterhood, who use it for school purposes. Poor Forrest! He had no taste for domestic life, and his happiest hours were passed upon the stage. Chance brought me frequently, when a boy, into the company of his wife and her sisters, Mrs. Voorhees and Miss Virginia Sinclair, and all my boyish sympathies were enlisted in their behalf and against the man who had slandered the woman who bore his name. I never pass the neighborhood of the old city residence of Forrest, on Twenty-second Street, near Eighth Avenue, but I think of this unhappy episode. Font Hill is the monument of his blasted hopes.

One would think it would be a pleasure to live in sight of the Palisades of the Hudson, but a gentleman who occupied a house on the banks of the Hudson for several years assures me that his experience was disenchanting. The sight of that tall barrier of rock and woods beyond the silver waves of the Hudson grew terribly monotonous. He wanted to throw it down and get a glimpse of the lovelier landscape that he knew lay beyond it. A sense of imprisonment crept over him, and he was glad at last to move away. His paradise of the Palisades had its apple tree and serpent. Viewed in this light, there was an element of reality to the joke of that wild wag, Fred Cozzens, who astonished the people of Kingsbridge and Yonkers by deliberately proposing to whitewash the Palisades. He argued that the effect would be wholesome to the eye, and refreshing to the public taste, while it would break the monotony of the landscape, and give them something bright and clean to look at instead of venerable and dusty rocks. Such was his apparent sincerity and earnestness that he found many sympathizers, and for a while the contest over the proposition raged hotly…

These papers…are simply the record of a random tour through places whose acquaintance I made as a boy, that recall the people of other days whom I have known.

“Felix,” said my grandmother, “always cut your cloth by your pattern.”

– Felix Oldboy

-

October 9, 2020 at 8:59 pm #1661

Cowboy Oak near the former Seton Hospital

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.