Home › Forums › The Industrial Era › Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad- Part 3: Through Kingsbridge

- This topic has 1 reply, 2 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 7 months ago by

COGGINSS.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

August 26, 2019 at 5:03 pm #1108

Previously, I wrote about the disruptions caused by the army of railroad workers and their blasting through Spuyten Duyvil Hill. However, the most disruptive leg of construction was still yet to come as the railroad wound its way through the most densely populated parts of the neighborhood.

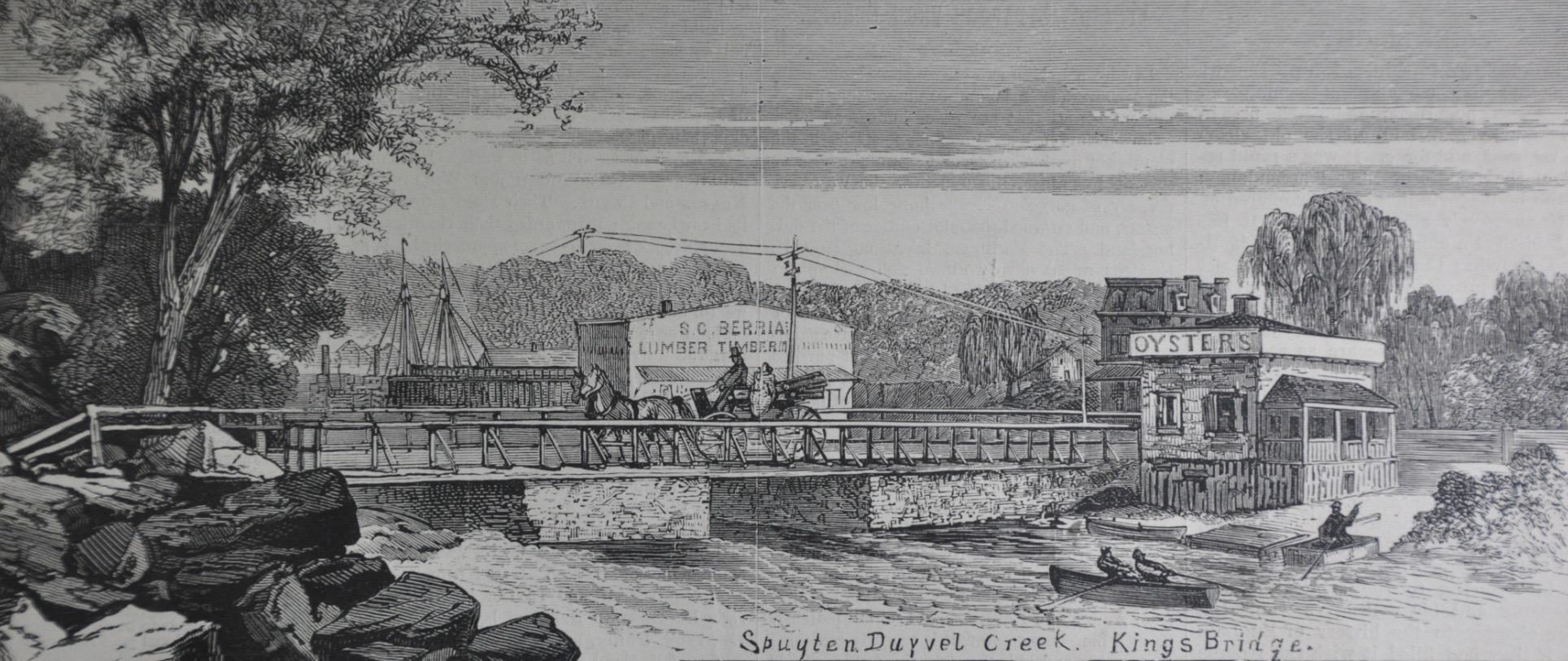

Trains coming from the Hudson River would travel over the bridge causeway and through the “rock cut.” From there, they would head northeast along the bank of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek. To make this route possible, track would be laid right over the main street that served the many homes and businesses situated along that bank (see illustration). Those buildings and the street that served them are no longer in existence. That area, sometimes referred to as the old village of Spuyten Duyvil once was home to foundry workers and the establishments that they frequented. That area is now part of the grounds of JFK High School, which largely sits atop the filled-in bed of Spuyten Duyvil Creek. The Commissioner of Highways, James Riley, noted that “the people of Spuyten Duyvil consider themselves very much injured by the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad.” This was due to the route of the railroad, which covered “the whole width of the highway by their two tracks, and cut off all the people owning lots and houses along that part of the road.”

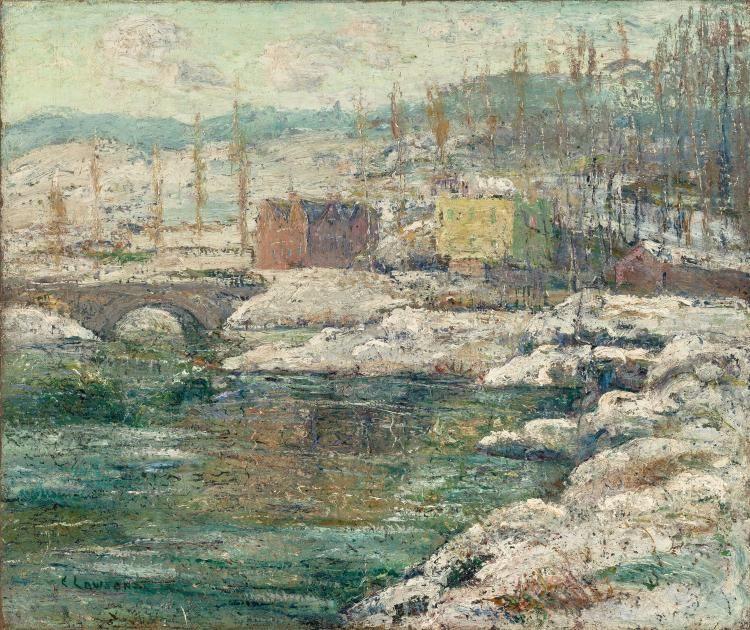

Tibbetts Creek in Winter by Ernest Lawson ca 1914 The most problematic feature of this leg of the railroad was where it crossed newly built Riverdale Ave. In 1865, an act of state legislature created the Commission for Riverdale Avenue, which oversaw construction of the 3 1/2 mile stretch of road, which extended from the southern line of the village of Yonkers to Kingsbridge. The commission had initially paid for and built a stone arch bridge to span Tibbett’s Brook where Riverdale Ave meets modern day W. 230th Street. To grasp the utility of this road and bridge, imagine for a moment that there was no Henry Hudson Parkway nor Henry Hudson Bridge as was the case in the 1800s. Now think about how important Riverdale Avenue and that little stone arch bridge was to the neighborhood. It was basically the only land route from Spuyten Duyvil and Riverdale to Kingsbridge and Manhattan unless you were willing to go all the way up to modern day W. 242nd Street to connect with Broadway there. And by the 1870s, the populations of Spuyten Duyvil and Riverdale were growing exponentially. So this intersection was a big deal. Local papers described it as “a great thoroughfare, crowded with heavy traffic.”

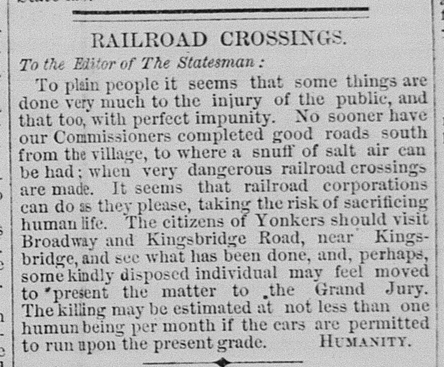

The neighborhood may have already been a little frustrated with this crucial spot on Riverdale Avenue when the stone bridge over Tibbett’s Brook collapsed in 1868 due to “defects of its construction” (according to the Yonkers Statesman). It did not take long for that to be replaced by a wide and sturdy iron bridge. But before the new bridge got too much use, tracks were laid right over the road at this intersection to the great dismay of locals. Uselessly kvetching about development in local papers is a great Riverdale tradition and an early example can be seen in the December 28, 1871 issue of the Yonkers Statesman.

Referring to the crossing at Riverdale Avenue, the highway commissioner would write “A more dangerous crossing can hardly be imagined” as trains speeding through the rock cut “cannot be seen for a hundred feet.”

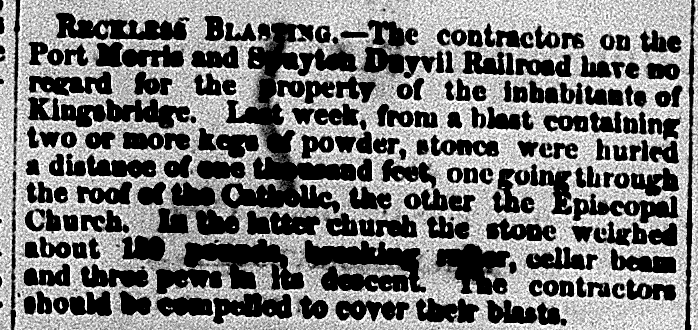

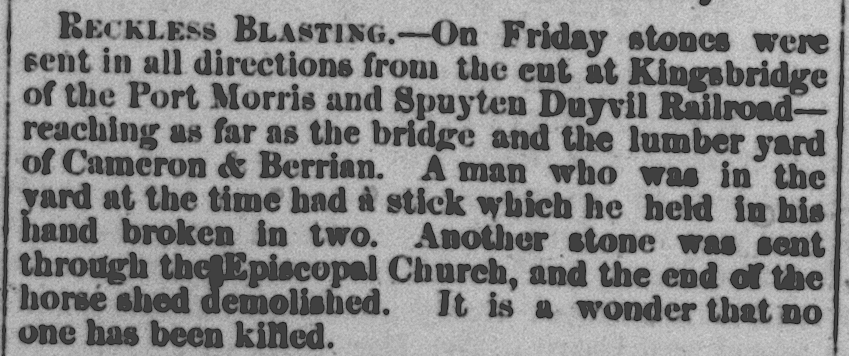

As the tracks approached the heart of the Kingsbridge neighborhood, it would again have to reckon with the elevation of the ground. The hill that you have to climb as you approach modern-day W. 231st Street and Kingsbridge Ave. (nearly 50 feet above sea-level) was too steep of a grade for locomotives. The underlying bedrock would need to be blasted and a viaduct built for the train. The same havoc that was let loose on Spuyten Duyvil would be felt in Kingsbridge:

Transcription: Reckless Blasting – The contractors on the Port Morris and Spuyten Duyvil Railroad have no regard for the property of the inhabitants of Kingsbridge. Last week, from a blast containing two or more kegs of powder, stones were hurled a distance of one thousand feet, one going through the roof of the Catholic, the other the Episcopal Church. In the latter church the stone weighed about 180 pounds, breaking [illegible] cellar beam and three pews in its descent…

Transcription: Reckless Blasting – The contractors on the Port Morris and Spuyten Duyvil Railroad have no regard for the property of the inhabitants of Kingsbridge. Last week, from a blast containing two or more kegs of powder, stones were hurled a distance of one thousand feet, one going through the roof of the Catholic, the other the Episcopal Church. In the latter church the stone weighed about 180 pounds, breaking [illegible] cellar beam and three pews in its descent…Another blast would send rock flying all the way to today’s W. 230th Street:

Berrian’s Lumber can be seen in this Harper’s drawing from 1873.

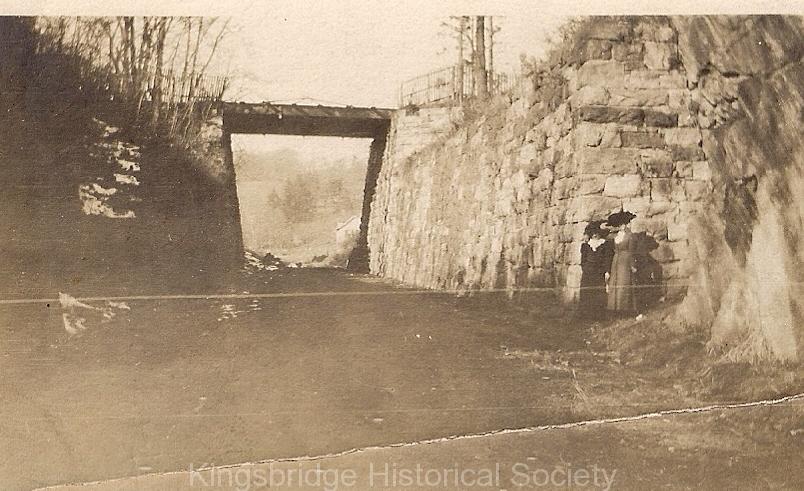

All of that blasting would create a viaduct for trains just south of 231st Street. Kingsbridge Avenue (or Church Street as it was then known) was a simple plank bridge over the viaduct.

The view is looking west through the defunct viaduct with Church Street (Kingsbridge Ave) as a simple plank overpass.

View looking east But having traversed today’s 231st Street, the line finally made it to Broadway, where there would be yet another street crossing that earned the ire of the neighborhood:

The letters to the editor, it seems, were fairly accurate in terms of safety concerns. There were plenty of stories over the span over the early 1870s about accidents on the railroad.

But not everyone was unhappy with the course and effects of the railroad. Wealthy property owners that had speculated in real estate stood to make a nifty profit by subdividing their holdings into small lots.

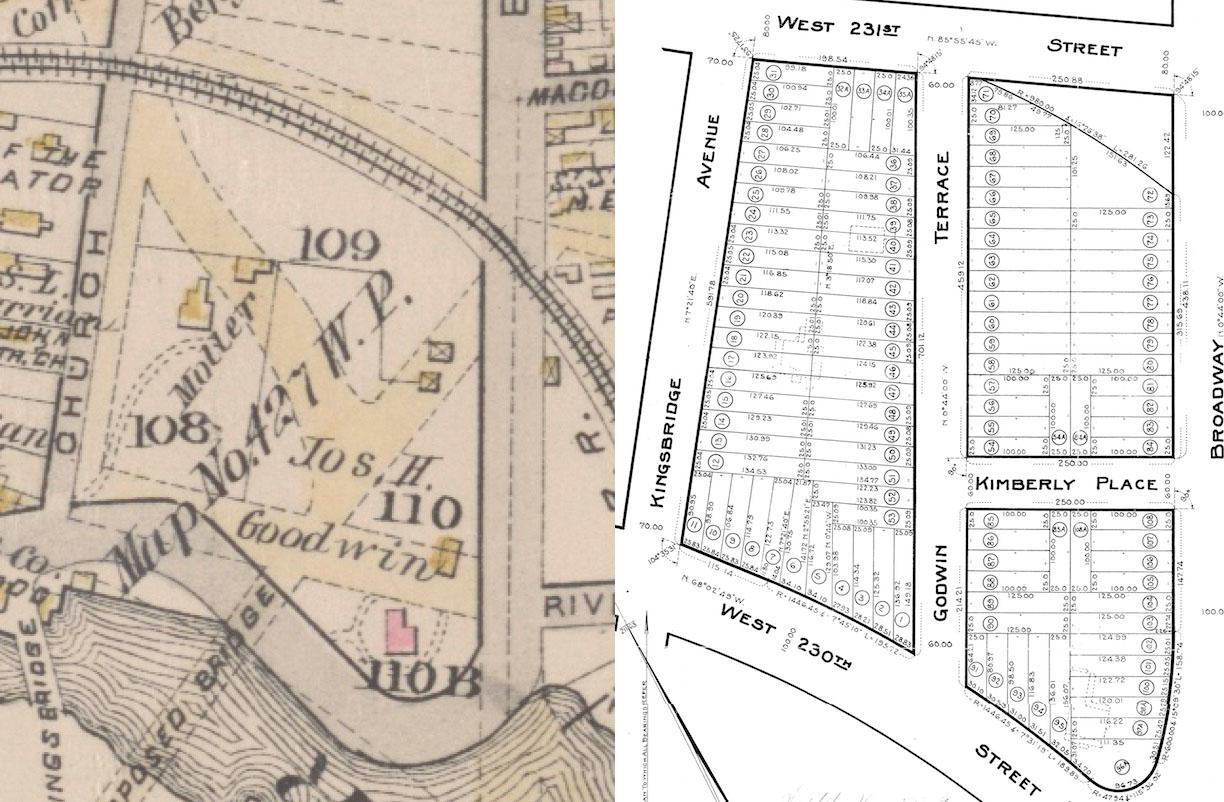

Speaking of real estate, there is very little evidence in this part of Kingsbridge that the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad ever traversed this bustling neighborhood. The only remaining artifact is the odd property lines at the northeast corner of 231st Street and Broadway. The route of the railroad clipped this corner so the corner lot had to be curved. You can see this in the rounded corner from the estate sale map for the Moller Estate in 1917.

Those property lines created a leftover triangle of land once the railroad was removed. Today, there are buildings on that triangle but the odd footprint is still visible from the W. 231st Street elevated subway station. Note the sharp acute angle of the “T Mobile” store on Broadway with W. 231st Street in the background.

-

August 26, 2019 at 6:23 pm #1110

Sounds like the impunity of development hasn’t changed that much.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.