Home › Forums › The Colonial Era › The Area Around the Van Cortlandt House in the 18th Century

Tagged: revolution, Van Cortlandt House Ghost

- This topic has 7 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 5 years, 8 months ago by

ndembowski.

ndembowski.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

June 25, 2018 at 6:41 pm #483

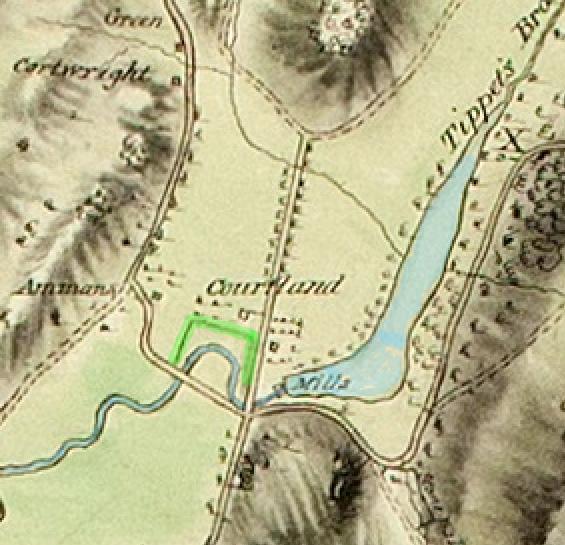

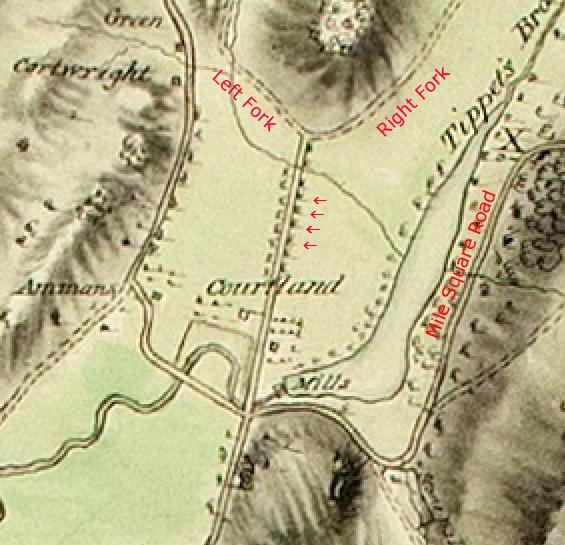

I am going to write a series of short posts about the area around the Van Cortlandt House during the 18th Century and the American Revolution. In order to get a “zoomed-out” geographical overview, I decided to annotate part of a map entitled “Map Of the Country Adjacent to Kingsbridge.” It was surveyed in 1781 “by Order of His Excellency General Sir Henry Clinton K.B..” It was made at a time that Sir Henry Clinton, then Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America, was worried about Washington’s army linking up with the French army in order to attack New York. This map was recently made available online by the William Clements Library, at the University of Michigan. Like all maps of this time, it leaves a lot out but it is probably the most complete map of the area that I have seen. Map key is below.

- Van Cortlandt House

- Older House

- Van Cortlandt Mills

- Thomas Emmons House

- Mill Pond (today’s Van Cortlandt Lake)

- Albany Post Road

- Mile Square Road

- Vault Hill

- Turtle Brook

- Path to Vault Hill

- Kortright House

- Isaac Green House

- Ryer House

- Breakneck Hill

- William Warner House

- Isaac Warner House

- Tibbett’s Brook

- Mount Pleasant (today’s Fieldston Campus)

- Upper Cortlandts (the estate of Frederick Van Cortlandt)

- Shortcut paths to Boston Post Road and William’s Bridge

- Path connecting Boston Post Road to Mile Square Road (today’s Jerome Avenue)

- Vermilyea House 1

- Abraham Vermilyea House

- Ogden House

- Gilbert Valentine House

- Mile Square Road (today’s Van Cortlandt Park East)

- Daniel DeVoe House

- Jesse Huested House

- Frederick DeVoe House

- Path to Albany Post Road from Mile Square Road (today’s McClean Avenue)

- Tibbett’s Brook Path (approximate location of Henry Hudson Parkway and Saw Mill River Parkway)

- Path to Tippett’s Neck (path to today’s Spuyten Duyvil Hill, approximately the same path as today’s Irwin Avenue)

Here’s the contemporary view:

When I look at this map, I am struck by a few things. First, the Van Cortlandts had more neighbors than you would have otherwise assumed. If you were to visit the Van Cortlandt House Museum today, think about how long it would take to walk to the intersection of 242nd Street and Broadway. That is where James Van Cortlandt’s closest neighbor, Thomas Emmons, lived–not that far at all. And there were clusters of homes all around Van Cortlandt Park. Second, I am amazed by how many of these colonial paths and roads still exist as modern-day paved roads. Van Cortlandt Park East is the Mile Square Road of yesteryear. McClean Avenue, Jerome Avenue, the Saw Mill River Parkway, and other roads were just paths back then but they did exist and the maps show them. These features are all shown on the customized map that I’ve been making here and you can compare maps and zoom in/out to see for yourself.

-

June 29, 2018 at 7:41 pm #485

The Roads and Paths around the Van Cortlandt House (Part 1 – The Albany Post Road)

Walking around the Van Cortlandt House in the park you will come across several intersecting trails and paths. Some of them have the look of old colonial-era roads. Some of those paths, in fact, harken back to that era–but some do not.

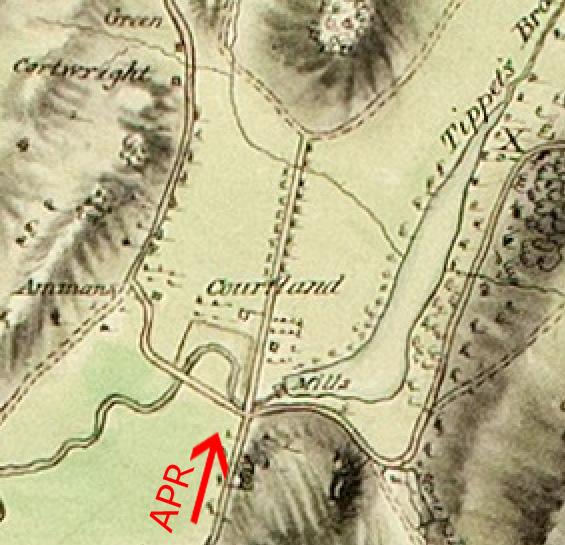

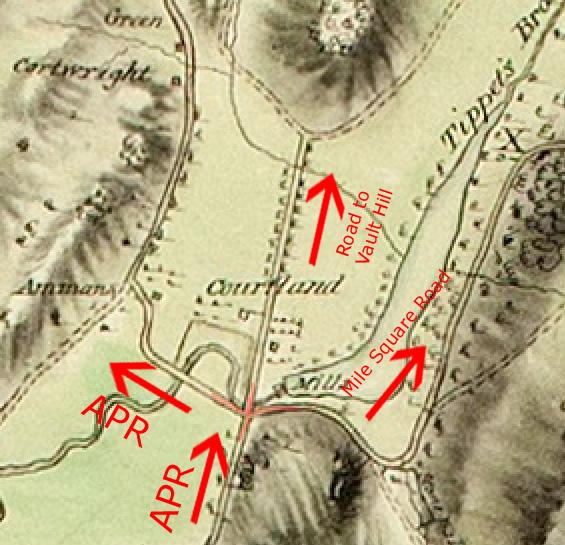

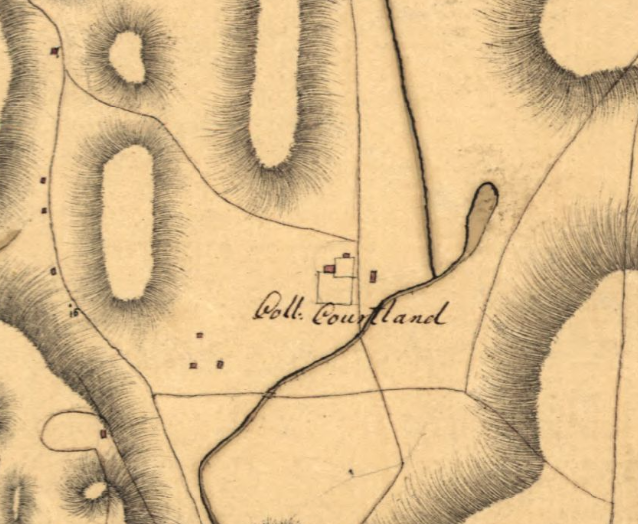

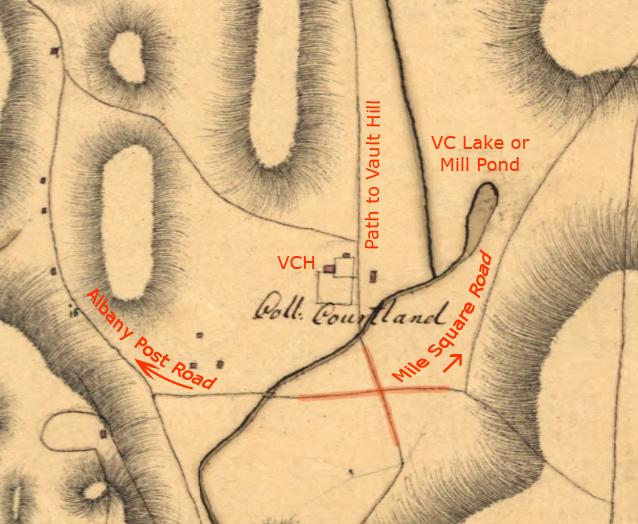

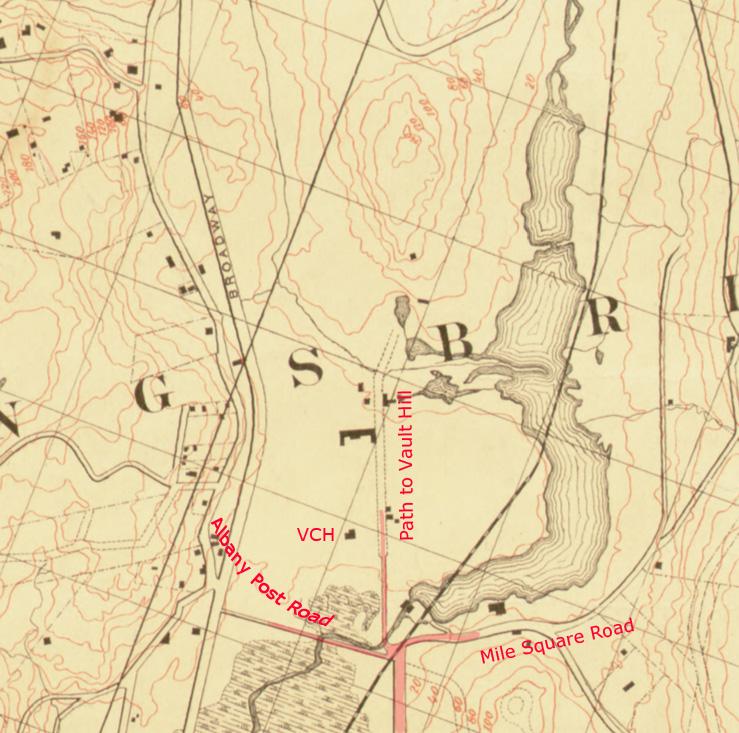

Zooming in a bit closer to the area adjacent to the VCH in the 1781 Clinton map, you will see a cross-intersection just southwest of the Van Cortlandt Mills. The road coming from the south is the Albany Post Road, or (“APR”).

At this intersection it splits off into three directions. The road heading west is the continuation of the Albany Post Road. The road that goes straight north from the intersection leads to Vault Hill, where the Van Cortlandt family buried their dead. The road that heads east from the intersection is the road to Mile Square or the Mile Square Road.

From this intersection, the Albany Post Road cut west and continued to about the site of present-day Broadway and 242nd Street. It continued north along what is still known as “Post Road.” It is fun to think that this part of one of America’s oldest roads still has its original name. In the old days, it wound its way north through Yonkers and along the Hudson River all the way to Albany. In colonial times, it was also known as the “turnpike” and the “River Road.” The photo below shows today’s street sign with “Post Rd.”

It would easy to forgive someone for thinking that the section of the Albany Post Road that went west through today’s park still exists in the form of the path pictured below.

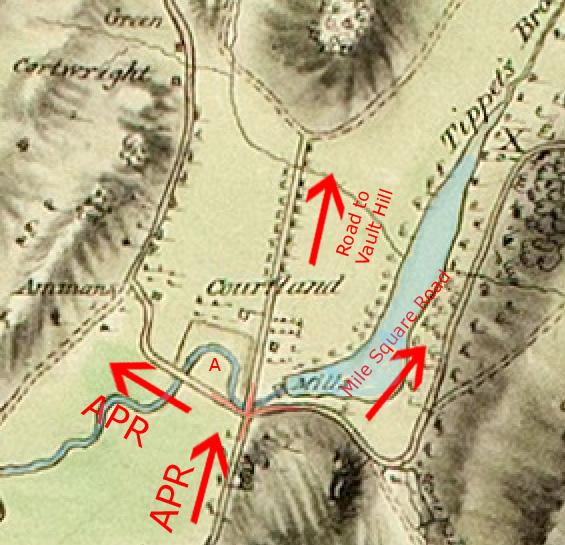

This path has a rustic look to it and travels in the same direction that the Albany Post Road would have as it traversed today’s park (east to west). And it is located south of the Van Cortlandt House as indicated in the 1781 Clinton map. However, there are a few reasons why this path cannot be a section of the old Albany Post Road. First of all, if you look carefully at the 1781 Clinton map you will see that Tibbett’s Brook (shaded blue on the below map) flowed north between the Van Cortlandt House and the Albany Post Road (in the spot indicated by an “A” on the below map). It would actually be impossible for Tibbett’s Brook to flow north in the area between the above-pictured path and the Van Cortlandt House. That area, where today there is a garden on the grounds of the house museum, is at a much higher elevation than Tibbett’s Brook and we all know that water can’t flow uphill. Secondly, the 1781 Clinton map indicates a much greater distance between the Van Cortlandt House and the Albany Post Road than exists between the Van Cortlandt House and the path pictured above.

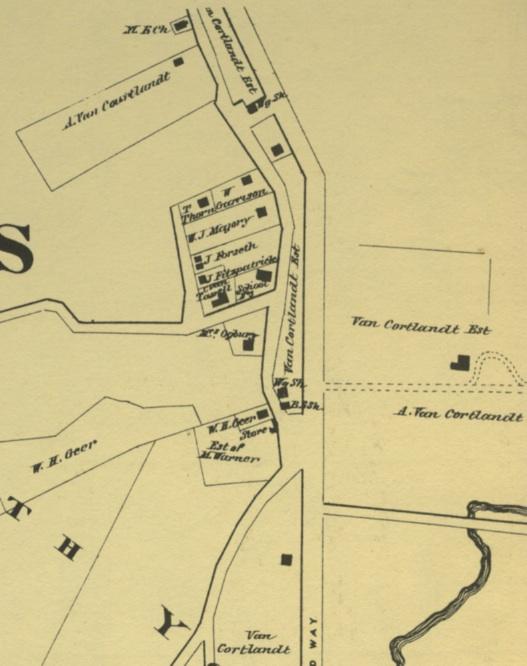

This is not to say that the path in today’s park is a new trail. While it is not a remnant of the Albany Post Road, it is actually a very old path. Have a look at the below section from an 1868 Beers, Ellis, and Soule Atlas of New York and Vicinity.

The Van Cortlandt House is on the right under the words “Van Cortlandt Est.” You’ll notice the presence of the present-day trail in the form of dotted lines on the map south of the house. This trail led from the Van Cortlandt House to the large intersection west of it, where there was a store, a school, a post office, and a blacksmith shop. This intersection was centered around the same area as the above photo showing the street signs. That was the core of the village of Mosholu. The laws of human laziness would seem to suggest the need for the path running along the fence of the Van Cortlandt House as it was a direct way to get from the Van Cortlandt House to this intersection. Further to the south, under Tibbett’s Brook in the above map, you’ll see the original section of the Albany Post Road running east to west just as in the 1781 map. That section of the Albany Post Road would intersect Broadway roughly in the area of today’s 242nd Street. The old Albany Post Road actually crossed today’s park roughly where today you find the path pictured below.

The below map produced by the Dept. of Public Parks in 1872 also shows the Albany Post Road hitting Broadway south of the Mosholu intersection. The Van Cortlandt House is indicated with the letters “VCH.”

You will also notice the contour line just to the south of the Van Cortlandt House. It represents a drop in elevation from the area just south of the house to the lower area where Tibbett’s Brook once flowed. You can descend that slope to the marshier area below by walking from the east/west path down this staircase that is about 150 feet south of the garden:

You can see that it would be impossible for Tibbett’s Brook to flow north up that hill. Interestingly, the contour line in the 1872 park map seems to mimic a set of three unlabeled line segments in the 1781 Clinton map, highlighted in lime green below. They seem to form a frame around that area of low elevation. Could they have represented a wall? It is difficult to say.

I will write more on the other roads and features around the house after July 4th. Enjoy Independence Day!

-

July 13, 2018 at 11:50 pm #486

The “cross” intersection that was south of the Van Cortlandt House appears in the 1781 Clinton map and other maps of that period (although I have yet to find one with the same level of detail as the 1781 Clinton map). Below is the 1781 Clinton map with the intersection highlighted in red.

The below image is a snippet taken from a fascinating 1778 British map held in the Library of Congress, entitled “Skecth [sic] of the road from Kings Bridge to White Plains.” As you can see, it is definitely more of a “sketch” than a detailed work of cartography.

The roads are drawn somewhat abstractly so see the below labels to align this sketch with the 1781 Clinton Map.

The purpose of the above map was to show the disposition of British troops, which held positions north of Kingsbridge (in Yonkers, Dobbs Ferry, etc.) at that time. This explains the lack of detail in this area. Nonetheless, the intersection where the Albany Post Road, Mile Square Road, and path to Vault Hill branch off is indicated roughly in the same area.

That same intersection is visible in the below snippet from another map from the Clements Library at the University of Michigan–although it does not come together in a neat cross as in the above maps. This is another British map from the revolution and it is even more abstract and lacking in detail.

The mill pond is not even depicted here but the paths and roads are discernable and labelled below.

100 years after the revolution, that intersection is still clearly visible in the below snippet from an 1872 Department of Public Parks map.

Annotated version:

Over 100 years later in today’s park–in roughly the same location as that old intersection–you see this:

The view is looking north just north of “Tibbett’s Wetland.” While this might not be in the exact same spot as that old intersection, it is very close. The path veering off to the left in the photo roughly follows the path of the Albany Post Road. The pool in today’s park prevents this path from continuing to Broadway. If you were to take the path to the right, you would be heading east below the south edge of Van Cortlandt Lake in roughly the same direction and location as the old Mile Square Road. If you were to continue straight ahead north (like the two kids in the photo), you would be travelling along the old path to Vault Hill. As you walk that path toward Vault Hill you will notice a stone wall on your right (pictured below), which gives it the look of an old colonial road. Although I cannot say how old that stone wall is, that path certainly seems to be in the same place and have the same trajectory as the old path that lead to Vault Hill in the 18th century.

If we take another look at the 1781 Clinton map, this path continued straight (over today’s Parade Ground) to the base of Vault Hill, where it forked into two smaller paths. The left fork connected to the Albany Post Road and the right fork headed north along the west bank of Tibbett’s Brook all the way to about where the Cross County Parkway is today. In other words, it generally follows the path of today’s Saw Mill River Parkway. In colonial times, it was only a path but it would have been important to the families that lived along the western banks of Tibbett’s Brook (the Posts and Oakleys).

Another curious feature of the Van Cortlandt property is depicted on the 1781 Clinton map. As the path to Vault Hill traverses the modern-day Parade Ground, the map shows that it is bordered by regularly-spaced objects on both sides (by the arrows). It seems like this must have been a tree-lined path. Another possibility is that it was some kind of elevated boardwalk to get over the field, which could get marshy at times. A tree-lined path seems likelier however.

Another curious feature of the Van Cortlandt property is depicted on the 1781 Clinton map. As the path to Vault Hill traverses the modern-day Parade Ground, the map shows that it is bordered by regularly-spaced objects on both sides (by the arrows). It seems like this must have been a tree-lined path. Another possibility is that it was some kind of elevated boardwalk to get over the field, which could get marshy at times. A tree-lined path seems likelier however.The Mile Square Road was a well-traversed lane as it offered residents of Mile Square (and parts of Eastchester via Hunt’s Bridge) the most direct route to Manhattan by land. Mile Square was a settlement, of about 1 square mile, composed of 7 farms that, notably, were not part of Philipsburg Manor. During the revolution, both armies occupied, fortified, and fought in Mile Square and the road was patrolled regularly by light troops and irregular cavalry that were based in the Kingsbridge area.

That pretty much covers the roads, paths, and trails around the Van Cortlandt House at that time. Coming up are posts about the watercourses, the buildings, the Van Cortlandts, and their neighbors.

-

July 23, 2018 at 2:43 pm #493

Before delving into the Van Cortlandts, the house, and their neighbors, I wanted to share what is a source of frustration for anyone trying to research or learn more about this property–the lack of information. Given the prominence of the home’s inhabitants, you would think that one of the gentlemen or ladies of the house would have left behind a diary, journal, or memoir of their life on Van Cortlandt Plantation. But no such accounts survive. Taking into account the size of the plantation, the many enslaved people that worked there, and the existence of two mills on the property, you would think that there might be a ledger, contracts, or correspondence relating to the business aspect of the plantation. But no such documentation, to my knowledge, has been found. Surely it must have existed at some point, and maybe some day it will turn up, but, for the time being, there is precious little primary source material to work with.

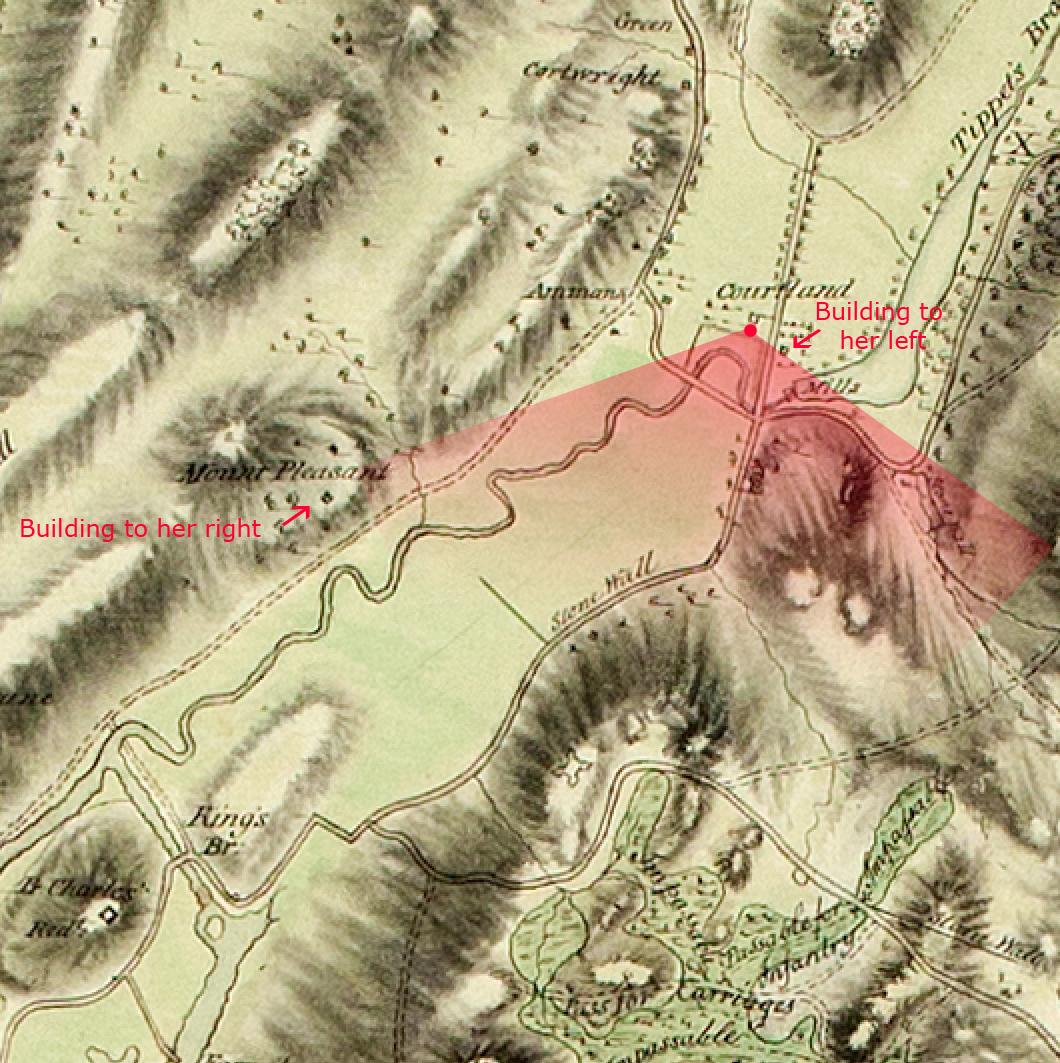

That is why I was particularly excited when I came across the Journal of Katharine Farnham Hay. On May 10, 1778 she came to the Van Cortlandt House, which she described as “a most Elegant house, a Beautifull Situation. the Mansion House of Col Cortlandt stood on an eminence a grand Building.” Standing in front of the house facing south, she observed, “in the front a fine Garden laid out in a Variety of figures adorn’d with Flowers. at the Bottom of the garden, their was a Sweet Canal, just beyond that was the great road to Albany. A most extensive prospect of Kingsbridge.” From the same vantage point, she goes on to describe two more nearby buildings: “a little on the right Stood another Elegant Building belonging to the family. on the left a small Neat House with a pretty Piazza commanded the same View of the other Buildings.”

If you use the below map snippet as a guide, she was standing at the spot indicated by the red dot and her field of vision would have been the area indicated by the red cone. You can see that she has a clear line of site through the Kingsbridge valley. Just before her is Tibbett’s Brook and the Albany Post Road.

The other two buildings that she described are interesting and I will write about them but first, a little bit about the author of the journal. Katharine Farnham Hay was travelling from Boston to New York City in an effort to reach her husband, John Hay, a British ship captain. On her way, she passed through an American patriot camp at White Plains, where her journey got complicated. The British lines were at Kingsbridge and the area between Kingsbridge and White Plains was contested ground. The opposing armies, wary of espionage, did not allow travellers to simply pass freely through their lines. At White Plains, she acquired an escort–a patriot Colonel named Hendly, who guided her to Kingsbridge under a white flag. They were stopped by a Hessian guard outside Kingsbridge, and she was held up there for a few days while the British, suspicious that she might be a spy, checked out her story. While in Kingsbridge, she stayed at a “publick house,” and the Van Cortlandt House and writes descriptively of her encounters with the Van Cortlandts and various British officers that were stationed in the area. The journal is a treasure of local history in the possession of the Massachusetts Historical Society, which transcribed and published it in 1997 in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, Vol. 109 (1997), pp. 102-122. The journal will help to shed a little light on the goings-on at the Van Cortlandt house at that time, about which very little is known.

-

July 27, 2018 at 11:01 pm #495

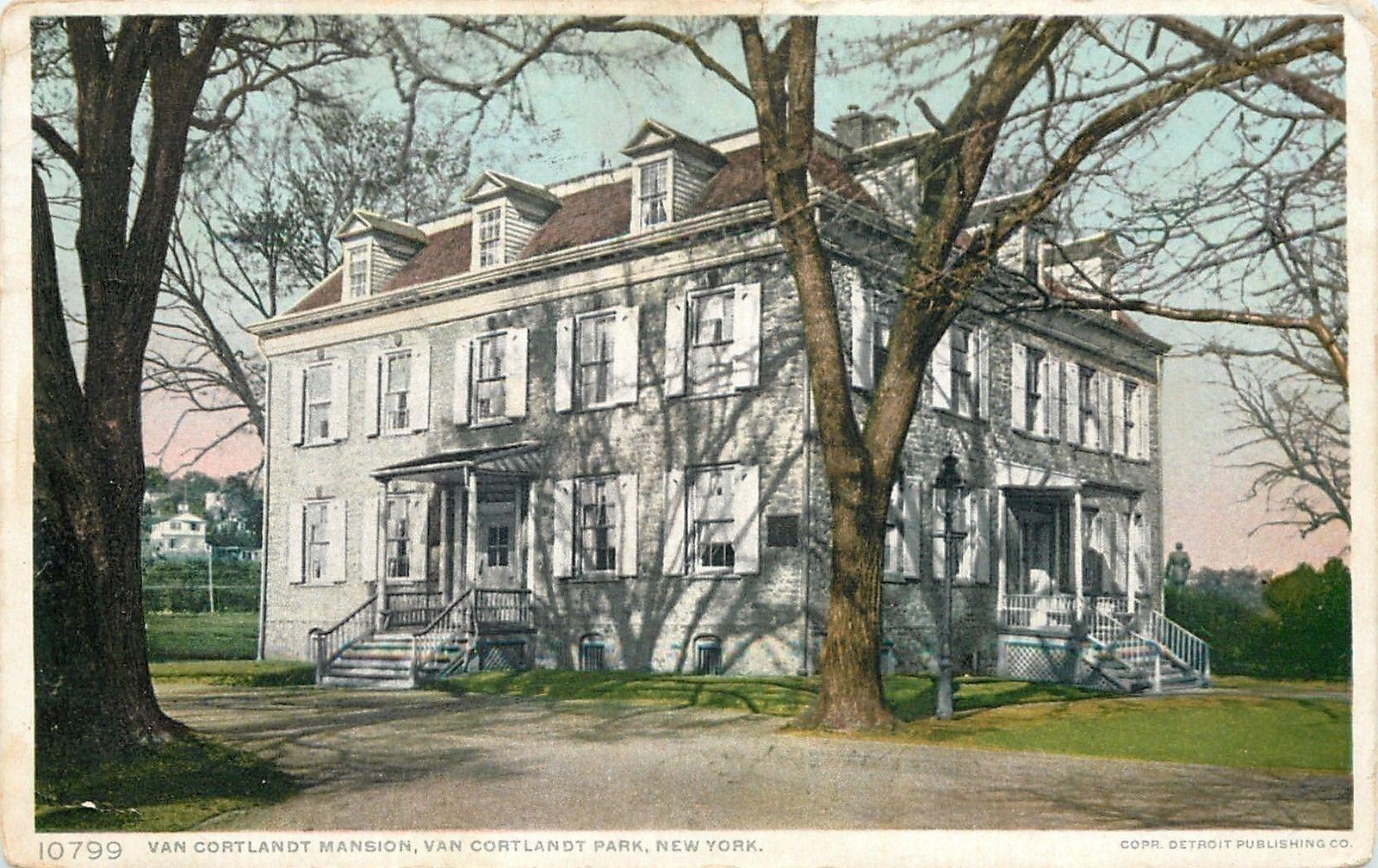

…which brings us to the Van Cortlandt House. Rather than repeat what others have already written, I will post links to some of what’s out there:

An interesting but brief history was published by the Colonial Dames of the State of New York in 1903. It was written by Catharine Van Cortlandt Mathews and does not have citations:

https://archive.org/details/historicalsketch00math

Christopher Ricciardi’s excellent Masters Thesis of 1997 gives a history of the family and the property starting on page 21. Before that is an interesting overview of the property in the 19th Century. Starting on page 30 is an archeological analysis:

http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/arch_reports/95.pdf

Another great resource is H. Arthur Bankoff and Frederick A. Winter’s report on the excavations around the Van Cortlandt House, which focuses on the enslaved people that worked at the house.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20853087

There certainly are many other articles and books that discuss the history of the house in detail. While I do have questions about the history of the property and the house, I will save those for later and instead report on the house as Katharine Farnham Hay saw it in 1778. By that time, the house was in the hands of Col. James Van Cortlandt (who retained the title of “colonel” despite not commanding regiments in any army). James Van Cortlandt lived there with his mother, Frances Jay Van Cortlandt. Ms. Hay’s writing can best be described as part journal, part letter. It is addressed to her sister but reads like a personal diary.

When the British army refused to allow her to proceed to New York City, her escort from the patriot camp, Colonel Henly (or Hendly), was ordered by the British to return to his camp. She was then forced to spend the night of May 10, 1778 in a shabby “publick house,” (possibly Cock’s Tavern) at today’s 230th Street and Broadway. Before leaving, however, Colonel Henly penned a letter addressed to James Van Cortlandt, “beging he wou’d take [Ms. Hay] under his protection, untill [she] could get admittance into York.” The next morning, Col. Emmerick of the British army showed up with permission for her to proceed to “Col. Cortlandts,”–AKA the Van Cortlandt House. She wrote a letter of her own asking James Van Cortlandt for the “Indulgence of his protection,” noting that she was “left without a Gentleman Servant or Carriage in a [P]ublick house, her Wretched feelings she can’t describe.”

Frances Jay Van Cortlandt Shortly thereafter, she “was surpris’d with a very pretty Horse, Mounted by a well dress’d Gentleman, rideing up to the Door. he dismounted came & aske’d for Mrs. Hay.” She writes “my heart leap’d for joy. I ran to receive him found him Brother to Col Cortland he receiv’d the Notes read them as his Brother was absent was so very kind as to procure liberty to Carry me to his House. this Gentleman told me he was unmarried liv’d with his Aged Mother who was very Sick if I cou’d make myself happy their I shou’d be very Welcome.”

This “well dress’d Gentleman” must have been Frederick Van Cortlandt II, brother of James, who had a home in the neighborhood at “Upper Cortlandts” near 238th Street and Broadway, I wrote a little bit about Upper Cortlandts here toward the bottom of the post. Apparently, Frederick was living in the Van Cortlandt House instead of his own home in order to look after his sick mother, who would pass away two years later in 1780.

She wrote that Frederick “made some excuse his not bringing a carriage with him, they were all in New York. I thought it an Idle Apology a Mile appear’d no more than a [Road].” After paying her bill, she “troted along at his side as Spry as a Sparrow as full of Chat as Magpie.” She continues “had you been by, you wou’d have suppos’d I had some design to have recommended myself (had not I have been married). after Walking a Mile we came to a most Elegant house…” She continues to describe the property in the words quoted in the previous post. She described Frederick Van Cortlandt’s home, “Upper Cortlandts,” as being “another Elegant Building belonging to the family.”

She writes on, “to this Hospitable Mansion I was Introduc’d. here the good Old Bachelor resided to take care of his Aged Mother & alleviate the insupportable weight of Old Age & disease. he led me into her bed Chamber there Sat the good old Lady [Frances Van Cortlandt] in her easy Chair, was very glad to See me but had got too far in her Dotage to be much of a companion. their was a very good kind of a Housekeeper & this Batchelor Mr Cortland is what you call a plain Man, a very tolerable figure, great Benevolence & Hospitality. from him I receiv’d great Civility & kindness in a very plain way (for he is no Courtier). I was quite happy spent a most agreeable Day.”

In the morning “in Come two Soldiers with written Orders for me to remove to Mount Morris at the Generals [John Vaughan] Quarters for further Orders.” This made Ms. Hay most uneasy until “Mr Cortland beg’d I woul’d not be uneasy he wou’d go with me. I thought him almost too good. just upon that in comes Col [Andreas] Emmerick. . . he gave leave that Mr. Cortland shou’d go with me. it was 6 Miles how shou’d we get a conveyance. they concluded to send for a Chair [or two wheeled carriage], as that is the common conveyance in this part of the Country. . . when the Chair came to the Door I confess I was mortified. I found some remains of pride, in short I can’t describe their kind of conveyance, if you recollect an Old Chair at Doctor Russells its more like that than anything I can think of.” Remember Frederick Van Cortlandt earlier said that his carriage was in New York, possibly with his brother James.

She met with General Vaughan in the Morris House at today’s Washington Heights. He told her that she would not have permission to proceed to New York City until her contacts there could verify her identity. He said “he wou’d have no Damn’d Smuggling work if the Damn’d Rebels wanted to get Intelligence it shou’d not be by Ladies.” She was ordered to return to the Van Cortlandt House with Frederick Van Cortlandt. She began to sink into despair but then James Van Cortlandt arrived:

This moment Summon’d to the parlour to see Col Cortland the Gentleman my Note was directed to, is just come from Town. I readily threw of my Reverie, run to the apartment, for he was a Gentleman I much wish’d to see. I found the family & Neighbours put great confidence in him. they were all wishing for him, they were Sure he cou’d do something for me, indeed the Neighbours seem’d to be much Interested in my Misfortune. they often came in to pity the poor Lady, & drop a tear of compassion over the wound they wanted the power to heal.

This moment Summon’d to the parlour to see Col Cortland the Gentleman my Note was directed to, is just come from Town. I readily threw of my Reverie, run to the apartment, for he was a Gentleman I much wish’d to see. I found the family & Neighbours put great confidence in him. they were all wishing for him, they were Sure he cou’d do something for me, indeed the Neighbours seem’d to be much Interested in my Misfortune. they often came in to pity the poor Lady, & drop a tear of compassion over the wound they wanted the power to heal.A couple of interesting notes about the neighborhood in the above passage: 1) That word spread relatively quickly among the neighborhood, perhaps emanating from the “publick house” where she first visited; and 2) that James Van Cortlandt was a man that the “Neighbours put great confidence in.”

Col Cortland received me very Genteelly, directly enter’d upon my Situation which was the reigning Topic in the Manor. he pour’d in the Balm of consolation, told me to be entirely easy. all things shou’d come right. he was well acquainted with the General. if my Intelligence was not agreeable the Next Day, he wou’d make Matters quite easy. we had quite a Social evening, I found him the Sensible agreeable companion. 10 OClock went to be had a fine Night.

May 13

At 8 OClock arose & Breakfasted. felt compos’d, enclineing to a fix’d Gloom, a burden to Chat, however Drag’d out the Morning with the Old Lady as well as I cou’d, Whilst her two Sons were amuseing themselves upon the farm. just before dinner, receiv’d permission from the General to remove into York with my Baggage, was to go to Col Emmericks quarters & not other person was to come with me. my new made friends rejoicd much at the Intelligence thought it very good & all my difficulties wou’d be soon over. Col Cortland said he wou’d go to Col Emmericks & give particular Orders to take good care of me, & procure me private lodgings until he cou’d find my friends. in a few days, he shou’d be in Town himself, if I then wanted any assistance he wou’d readily do anything in his power for me. I felt more gratitude for his kindness than I can express. . . after takeing a Glass of Wine, to Cheer up my Spirits & make the heart feell more joyous, Col Cortland & myself got into the Chair, the Curious York Vehicle that I mention’d before, with an Old Horse that cou’d but just draw this Pompous conveyance, he made a good many Apologies for the Horse as it was the only one that wou’d go in a Carriage he had out of the city. I was so Afraid of falling out, that I exerted all of my Strength, to hold myself in, we really laugh’d very hearty, by the time we got to Emmerick quarters, the Col then step’d out, & this Young Officer Step’d in. after very particular directions to the Young Officer, & his assuring them he wou’d do everything to Serve me, we proceeded to the City.

At 8 OClock arose & Breakfasted. felt compos’d, enclineing to a fix’d Gloom, a burden to Chat, however Drag’d out the Morning with the Old Lady as well as I cou’d, Whilst her two Sons were amuseing themselves upon the farm. just before dinner, receiv’d permission from the General to remove into York with my Baggage, was to go to Col Emmericks quarters & not other person was to come with me. my new made friends rejoicd much at the Intelligence thought it very good & all my difficulties wou’d be soon over. Col Cortland said he wou’d go to Col Emmericks & give particular Orders to take good care of me, & procure me private lodgings until he cou’d find my friends. in a few days, he shou’d be in Town himself, if I then wanted any assistance he wou’d readily do anything in his power for me. I felt more gratitude for his kindness than I can express. . . after takeing a Glass of Wine, to Cheer up my Spirits & make the heart feell more joyous, Col Cortland & myself got into the Chair, the Curious York Vehicle that I mention’d before, with an Old Horse that cou’d but just draw this Pompous conveyance, he made a good many Apologies for the Horse as it was the only one that wou’d go in a Carriage he had out of the city. I was so Afraid of falling out, that I exerted all of my Strength, to hold myself in, we really laugh’d very hearty, by the time we got to Emmerick quarters, the Col then step’d out, & this Young Officer Step’d in. after very particular directions to the Young Officer, & his assuring them he wou’d do everything to Serve me, we proceeded to the City.That is the extent of Ms. Hay’s interactions with the Van Cortlandts as recorded in the journal. It gives some idea of the character of Frederick and James Van Cortlandt, who come across as respectable and generous to Ms. Hay. I am curious if the “very good kind of a Housekeeper” that she describes was one of the four enslaved women that Frances Van Cortlandt describes in her will. I also wonder what the vehicle, which she calls a “chair” looked liked in light of her disgust of the sight of it. Frederick Van Cortlandt I, in his will, left a “two and four wheal chaise” to Frances. Possibly this was the same “chair.”

The journal raises questions as to the stance of this branch of the Van Cortlandt family during the revolution, a topic which always seemed somewhat murky to me, which I will address in the next post.

-

July 29, 2018 at 10:36 pm #496

I was asked by students of PS 81, Robert J Christen School in Woodlawn about ghosts at the Van Cortlandt Mansion. The students recently visited the Morris-Jumel Mansion in Manhattan and wanted information before they visited the Van Cortlandt Mansion. Except for the strange and scary gargoyles that adorned the VC Mansion, I had never heard of a VC Ghost story. Until I went home that night and started my research. Sure enough….I found out that the ghost of Captain Rowe, of the British Pruicsbank Jaegers roams the house during the night of his death. He was shot while on his last patrol by men of Captain Pray’s company. He resigned his commission, in order to get married to Elizabeth Fowler of Harlem. His wounded body was laid to care in the Washington Bedroom at VC. When his bride arrived with her mother, Captain Rowe died in her arms. Part of the story can be found at https://books.google.com/books?id=E1A2AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA214&lpg=PA214&dq=Pruicsbank+Jaegers&source=bl&ots=ZYRHrsVMSx&sig=eAWV05VXhfl9Y2vqyIsM_ClL8AM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjMhPKMrsXcAhVLVd8KHXJzAxEQ6AEwAXoECAMQAQ#v=onepage&q=Pruicsbank%20Jaegers&f=false

-

July 29, 2018 at 10:43 pm #497

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="851"]

Place where Captain Rowe Died in his bride to be arms. ( Elizabeth Fowler )[/caption]

Place where Captain Rowe Died in his bride to be arms. ( Elizabeth Fowler )[/caption] -

August 19, 2018 at 1:29 am #498

That is definitely a cool and interesting story, Tom. It just goes to show the powerful psychological impression that the Hessians left on the early Americans. After all, the headless horseman was also supposed to be a Hessian ghost. They should have a ghost story reading at the Van Cortlandt House on Halloween! Imagine how spooky that place would be in the dark with only candlelight.

Another thing that your reply makes me think of is all of the people that are credited for staying at the Van Cortlandt House during the revolution, such as the Hessians that you mentioned, and the frustrating lack of primary source documentary evidence to prove it. I have heard that Washington stayed there up to 3 times as well as Banastre Tarleton and the Hessians. But credible evidence that all of these visits actually occurred is pretty hard to come by.

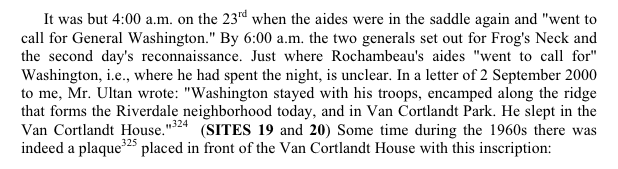

Take Washington, for example. There are a few dates floating around that he stayed at the VCH. You were kind enough to share this very interesting document with me relating to a time that Washington’s forces were camped in the Kingsbridge area:

http://www.hudsonrivervalley.org/themes/pdfs/rochambeau_revolutionary_route.pdf

It states:

If you go to footnote 324, it reads:

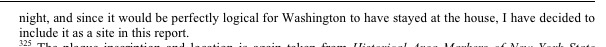

Lloyd Ultan certainly knows his stuff but even the author seems to insinuate that this isn’t exactly ironclad evidence. It seems that Lloyd perhaps got the information from the <span style=”text-decoration: underline;”>Itinerary of General Washington</span>, which you also shared with me:

The last statement, that Washington and Rochambeau dined at the Van Cortlandt house on 7/23/1781, is not a quote nor an excerpt from Washington’s diary but rather an unattributed editor’s note. So the question is, where did the editor get that information? Washington’s diary from that day reads:

23d. Went upon Frogs Neck, to see what communication could be had with Long Isld. The Engineers attending with Instrumts. to measure the distance across found it to be [ ] Yards.1

Having finished the reconnoitre without damage—a few harmless shot only being fired at us—we Marched back about Six o’clock by the same routs we went down & a reversed order of March and arrived in Camp about Midnight.

If the editor’s note in the itinerary is correct, it means that Washington and Rochambeau dined at the VCH after midnight, which seems a little odd. I am not saying Washington did not spend the night there. I just think that there really isn’t any slam dunk evidence that he did–at least not on that day.

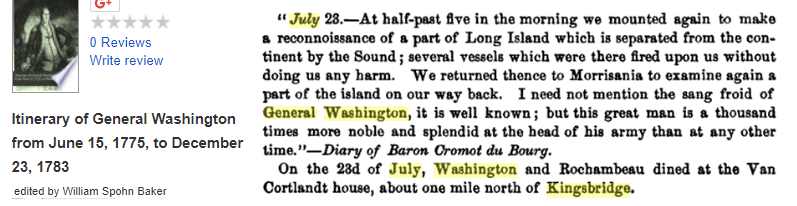

He visited the house earlier during the July 1781 reconnaissance. The following is an excerpt of a British report written by Captain Ludwig August Marquard, aide-de-camp to Knyphuasen, who was operating an intelligence operation at the Morris House:

The report is dated 7/4/1781 and refers to one part of a large patriot force that clashed with the British/Hessians at King’s Bridge on the third. I found it in the Clinton papers at the William Clements Library at the University of Michigan. “Mr. Courtland” would have been Frederick Van Cortlandt. James Van Cortlandt, who was living at the mansion house in today’s VC Park had already died and the other brother, Augustus, was living in the city. This raises the question: Did Washington visit the the Van Cortlandt House in today’s park that day or did he visit Frederick’s house at “Upper Cortlandts” near today’s 238th Street and Waldo Ave? The report states that Generals Washington and Parsons came to “his house,” but I tend to think that Washington came to the mansion in the park on the morning of the third for two reasons. First, as we see in the diary of Katharine Farnham Hay, Frederick Van Cortlandt did live at the mansion in today’s park when his brother, James, was away. Second, Washington and Parsons were marching from Mile Square that morning and ended up skirmishing with the Hessian jaegers at Fort Independence. This suggests that Washington came to the Van Cortlandt house in today’s park as it is located at the end of the road from Mile Square and was closer to Fort Independence than Upper Cortlandts.

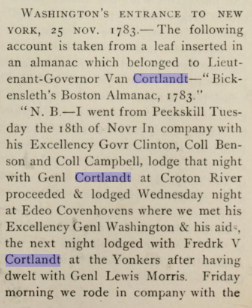

The only primary source evidence I have ever seen that Washington may have spent the night at the Van Cortlandt House in the park comes courtesy of Pierre Van Cortlandt. This is from the <span style=”text-decoration: underline;”>Magazine of American History</span> and it relates to the days leading up to Evacuation Day:

Again, it doesn’t indicate if Washington stayed at Frederick Van Cortlandt’s “elegant” house at Upper Cortlandts or the mansion house in today’s park. I think Pierre Van Cortlandt’s note probably refers to the latter for the same reasons expressed earlier.

Despite the sketchiness of the evidence, I bet Washington spent the night in the mansion house more than once as did other prominent figures from the revolution. I couldn’t find any evidence that Banastre Tarleton ever stayed at the house but it would make sense if he did as well.

The other question raised by the above documents is: Whose side were the Van Cortlandt brothers on during the war? These documents show Frederick Van Cortlandt as willing to provide intelligence to the British. The Farnham Hay diary indicates that James and Frederick Van Cortlandt seemed to hold sway with (and have the respect of) the British officers in the area. I will probably start a new post to delve into the Van Cortlandt brothers’ roles during the revolution.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.