Home › Forums › The Colonial Era › The First Land Deal pt. 3

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 3 years, 7 months ago by

ndembowski.

ndembowski.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

September 24, 2020 at 6:58 pm #1642

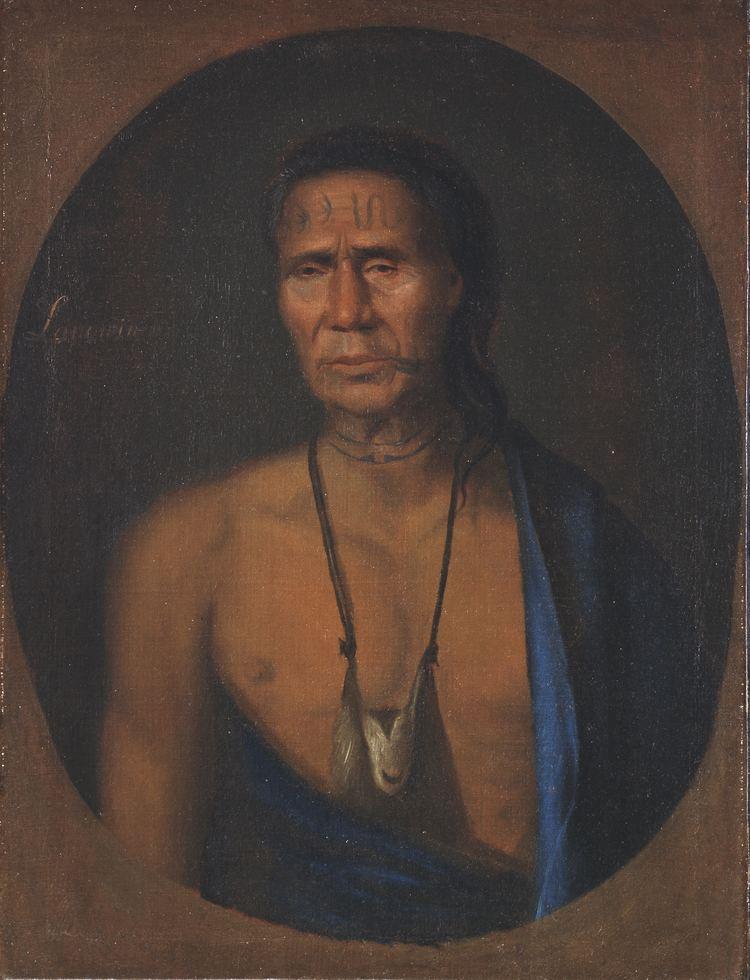

Lappawinsoe – Lenape Sachem who lived contemporaneously with Claes This is a continuation of my investigation into the land deal between the Dutch colonist, Adriaen Van Der Donck, and the local Munsee people. Part 1 is here and Part 2 is here:

In 1666, a Munsee man called “Claes ye Indian” was named in New York colony’s Executive Council minutes as one of the people who sold land in our area to Adrian Van Der Donck back in 1646. Then in 1676, Claes reappeared in the record alongside other Munsee people to say that they had, in fact, not been paid for the land. So what is the true story with this land “purchase” and who was Claes? While we have documents, government records, and correspondence to help us better understand Adrian Van Der Donck as a historical figure, there is far less information about Claes.

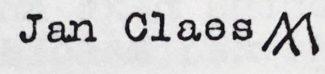

But we start to get an idea of who Claes was by the frequency that his name appears in colonial documents. Robert Grumet has identified up to 23 land deeds and other documents from 1666-1714 that refer to a Munsee man from our region named Claes, (a.k.a. Jan Claes, Claus, Nicholas, or Towachkack). The land deeds deal with property on both sides of the Hudson River centered in the lower Hudson River Valley (Bergen County, Yonkers, Tappan, The Bronx, etc.). Claes signed those deeds with an image of two mountains as his signature and the Clausland Mountains near Nyack are likely named after him. Unlike some other Munsee individuals that were named in documents, Claes is not usually referred to as a Sachem or chief. Rather he seems mostly to have served as a witness, translator and interpreter in most transactions. He was also something of a cultural liaison. When the Reverend Charles Wolley visited New York from England in 1678, he kept a journal in which he described Munsee society. He wrote of having received “good informations from one Claus an Indian, otherwise called Nicholas by the English, but Claus by the Dutch, with whom I was much acquainted.” But he was also a diplomat, such as in 1690 when he convinced Tappan fighters to join with the English government in their war against the French colonies. His ability to communicate and negotiate with Europeans accounts for his numerous appearances in colonial era documents. Another European visitor, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, encountered a group of various Native people in 1681 near today’s Toledo, Ohio. They were all refugees from the English colonies along the east coast, including “Manathes” (or Manhattan). They had left their land back east in search of a decent place to live and hunt and among them was a man named “Klas!” Both Claes and Van der Donck were men whose lives took them far from home, moved between worlds, and had a better than average understanding of the other’s culture.

Signature of Claes But in the deal for the northwest Bronx, Claes’ role was that of a co-seller. The first named seller is Tackareek, “cheife” of the “Indian Proprietors.” Claes is listed second. The Executive Council minutes characterized Claes’ connection to the land somewhat amorphously: “Claes ye Indian having an interest in a part [of the land] Acknowledged to have sold it and received satisfaction of Van Der Dunck.”

Mirroring the fact that there were two “sellers,” Van Der Donck referred to his purchase as consisting of two tracts purchased at different times. In a 1652 letter, Van der Donck wrote that he first purchased the northern tract of his patent in today’s Yonkers where he erected a saw mill. The second part of his purchase was “a valley of 30 or 40 morgen, with another handsome vale . . . stretching as far as Paprinimen called by our people, in spite of the dyvel where [Van der Donck] was determined to fix his residence.” This latter portion is the southern tract and it refers to today’s Kingsbridge stretching to the Spuyten Duvyil Creek. Could Claes’s “interest” in the land mean that he lived in (or was the descendant of someone who lived in) our neighborhood? It is impossible to know for sure but there is strong evidence to support that idea.

Fast forward to the year 1701 — 25 years after Claes returned to tell the governor that he had not been paid for the land in the Northwest Bronx. By that time, the area had changed quite a bit. There was a small settlement of colonists living in today’s Van Cortlandt Park–many of whom were members of the Tippett and Betts families. The land that was included in the Van Der Donck deal had already changed hands several times and had been subdivided into lots owned by different families of colonists. At about that time a wealthy and influential New York City merchant named Jacobus van Cortlandt took an interest in this area and began buying up those subdivided tracts in order to put together the large estate that would become Van Cortlandt Park. Despite having purchased the land from European colonists, he still had to satisfy Claes’ claim to have a clear title. In 1701 Van Cortlandt cut a deal with “Clause Dewilt,” which is how a Dutchman would say “Claes the Indian.” It reads:

To all Christian people and others to whom these presents shall come, Clause Dewilt, Karakapacomont and her son Nemerau sendeth greeting: Know yee, that wee, the said Clause Dewilt, Karacapacomont, and Nemerau, native Indians and former proprietors of a certain tract of land lying the in county of Westchester in the province of New York in America, commonly called and known by the name of the old Younckers, now in possession of Jacobus van Cortlandt of the city of New York, merchant, and the heirs of the Betts and Tippetts, for and in consideration of two fathoms of duffils and one pound two shillings and sixpence current money of New York in hand paid unto us by the said Jacobus van Cortlandt, have remitted, released, and forever quit claimed unto the said Jacobus van Cortlandt, and to the heirs of the Betts and Tippets, and to their heirs and assigns forever, all our right, title, and interest, which we ever had, now have, or hereafter may have or claim to the said tract of land called the old Younckers, and to every part and parcel thereof, and do hereby acknowledge the above consideration to be in full of all dues and demands whatsoever, for the said tract of land and premises, to have and to hold the said tract of land called the old Younckers, to the said Jacobus van Cortlandt and the heirs of the Betts and Tippetts, their heires and assignees forever, witness our hands and seals the 13th of August 1701.

Sealed and delivered in the presence

Gualter du Bois

William Sharpes

Claass Dewilt

Karacapacomont

NemerauWhile there is no evidence that Claes could read or write, colonial deeds were customarily read aloud in the presence of both parties before they were signed (a great many colonists were also illiterate). It is noteworthy that this document refers only to the land possessed by the Tippett and Betts families and Van Cortlandt. Those lands did not represent the entirety of the land acquired by Van Der Donck in 1646–only the southern portion in the Kingsbridge area. The document also specifically states that Claes, Karacapacomont, and Nemerau were “former proprietors” of the land in question. While local Munsee did not always live in the same exact settlement location, Claes and the others were clearly from our neighborhood in one way or another.

How fair was this deal? It depends. If Claes and the other Munsee were already partially paid by Van der Donck and only needed a little something extra to seal the deal and make it official, this might not be as unfair as it initially looks. Given the previous confusion over payments due, this seems plausible. However, if one pound, 2 shillings, sixpence, and a few yards of cloth were the only compensation the Munsee received for the hundreds of acres that made up “the Old Younckers” then they received far, far less than the land was worth to colonists at the time. The 1695 estate inventory of Joseph Hadley, who lived in today’s Van Cortlandt Park, included just a small portion of this land–sixty acres–and that was valued at over 5 pounds alone. The other possibility is that Claes had in fact been paid in full as was indicated in the 1666 Council Minutes but that he took advantage of a turbulent situation in the colonies in order to get paid yet again for the same land. Claes would not have been the only Munsee person to think of doing this. Ultimately, it is impossible to know what really happened without more information.

But why would Claes and the other local Munsee agree to sell their land? What was the power dynamic between colonist and colonized in 1646 and later in 1701? I will try to address that in the next and final part of this story.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.