Home › Forums › The Colonial Era › Visitors to the King’s Bridge (#2)

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 7 years, 10 months ago by

ndembowski.

ndembowski.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

September 18, 2016 at 5:07 pm #164

Even decades before the construction of the King’s Bridge in 1693, the area around modern 230th Street and Broadway was still an important stop for travelers to New York City. And centuries before Dunkin Donuts arrived on that corner, it was still a good place to get a cup of hot chocolate–and oysters for that matter. At that time the area was known as Spuyten Duyvil or Paprinnemin, which was the Munsee Indian name for the hummock, or low hill, on The Bronx side of the creek. The story begins in 1668, when Johannes Verveleen petitioned the English colonial governor, Francis Lovelace, to move his ferry operation from New Harlem to Spuyten Duyvil. Lovelace thought it was a good idea and ordered the mayor and alderman to make it happen. In 1669 the colonial government made an agreement with Verveleen to:

Erect & provide a good & sufficient Dwelling house, upon ye Island or Neck of Land knowne by ye name Papiriniman, where he shall be furnish’t wth three or fower good Bedds, for ye Entertainment of Strangers, as also wth Provisions at all Seasons, for them their horses & Cattle upon all Occasions.”

Verveleen’s memory is honored by “Verveleen Place,” a short dead end street off Broadway with no addresses. Paprinnemin, the hummock, with its “summit” near 232nd and Broadway was an island, at least at high tide. Spuyten Duyvil Creek was to its south, Tibbett’s brook to the west and north, and a tidal inlet on the east. It was here, probably near 230th and Broadway, that the government ordered the modest “dwelling house” to be built. Verveleen was instructed “That in Case he lodges any pson one night he is to have 6. pence p night in Case they have a bed wth sheets and wthout sheets two pence in Silver.” Sheets–now that’s luxury! Verveleen was also appointed constable of Fordham and charged with building a bridge “over ye meadow ground to ye Towne of Fordham” to make travel over the tidal inlet easier.

Verveleen’s monopoly on trade did not last long. In 1693 Frederick Philipse obtained a charter for Philipsburg Manor. In part it read, “unto said Frederick Philipse . . . the aforesaid neck or island of land called Paparinemo, and the meadow thereunto belonging, with power, authority, and privilege to erect and build a dam bridge upon the aforesaid ferry at Spitendevil or Paparinemo and to receive rates and tolls of all passengers and for droves of cattle. . . and it is our royal will and pleasure. . . the aforesaid bridge to be from henceforth called Kingsbridge in the manor of Philipseborough.”

One traveler, Dr. Alexander Hamilton (not THE Alexander Hamilton) made use of Philipse’s bridge and the tavern on his way to the city in 1744. His diary entry of 8/ 30:

Coming from [New Rochelle] att 4 o’clock I put up this night att Doughty’s who keeps house att Kingsbridge, a fat man much troubled with the rheumatism and of a hasty, passionate temper. I supped upon roasted oysters, while my landlord eat roasted ears of corn att another table. He kept the whole house in a stirr to serve him and yet could not be pleased. This night proved very stormy and threatened rain. I was disturbed again in my rest by the noise of a heavy tread of a foot in the room above. That wherein I lay was so large and lofty that any noise echoed as if it had been in a church.

We learn much about the tavern from this description: the name of the proprietor, Doughty; the food that was served there; and that the building was a large two-story structure. Perhaps the tavern had been expanded since the days of Verveleen.

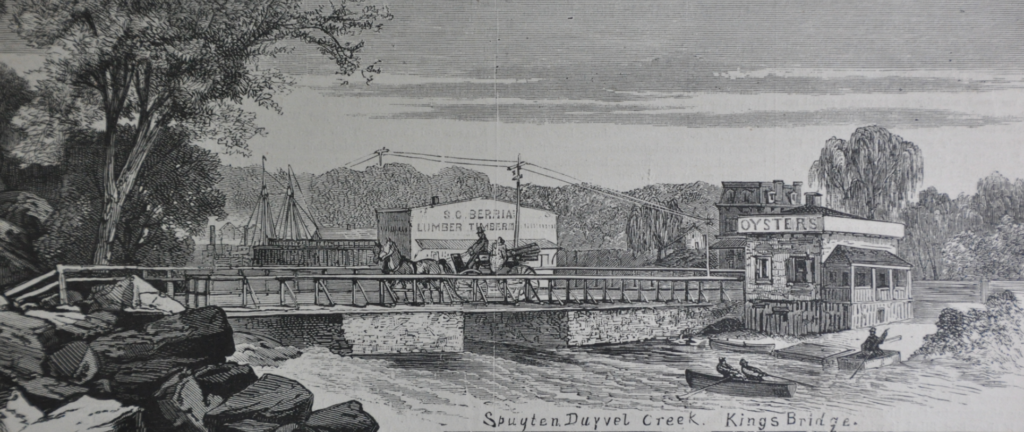

Oysters were still being sold at the end of the King’s Bridge in the late 1800’s. Hamilton’s entry from the next day is even more interesting:

I breakfasted at Doughty’s. My landlord put himself in a passion because his daughter was tardy in getting up to make my chocolate. He spoke so thick in his anger and in so sharp a key that I did not comprehend what he said. I saw about 10 Indians fishing for oysters in the gutt before the door. The wretches waded about stark naked and threw the oysters, as they picked them up with their hands, into baskets that hung upon their left shoulder. They are a lazy, indolent generation and would rather starve than work att any time, but being unaquainted with our luxury, nature in them has few demands, which are easily satisfied.

The jarring sense of supremacy over the Indians is hard to ignore here. How can someone who is sipping chocolate in a tavern characterize Indians that are harvesting their own food as “lazy” and “indolent?”

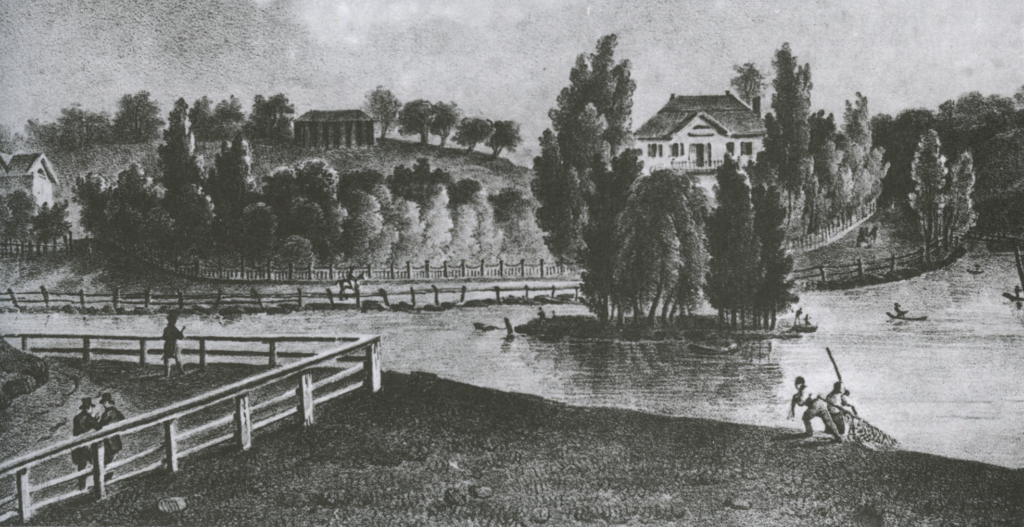

J. Milbert’s 1819 depiction of the area depicts a similar scene with locals harvesting oysters right out of the creek. The house behind the little island is the Macomb mansion, which may have incorporated the tavern in whole or in part.

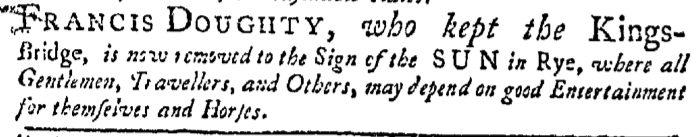

Doughty thought enough of his reputation to tout it in this 1748 advertisement in the New-York Gazette. The fact that oysters were available in the creek seems to suggest that the tavern served locally harvested fare as well as imported (chocolate). The fact that the tavern was a multi-story building indicates that it may have been a popular establishment–or at least that the place was designed to accommodate a large number of guests.

Hamilton paints a fascinating picture of the area around the tavern that raises as many questions as it does answers. It is interesting to learn that Indians and colonists were mingling closely in this area. Also, it seems that these 10 Indians were, at least in their diet and dress, living a traditional Lenape lifestyle. Where did they live, in the caves in today’s Inwood Park? How long did this coexistence last?

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.