The Hadley House at 5122 Post Road

Is this the oldest house in The Bronx?

By Nick Dembowski

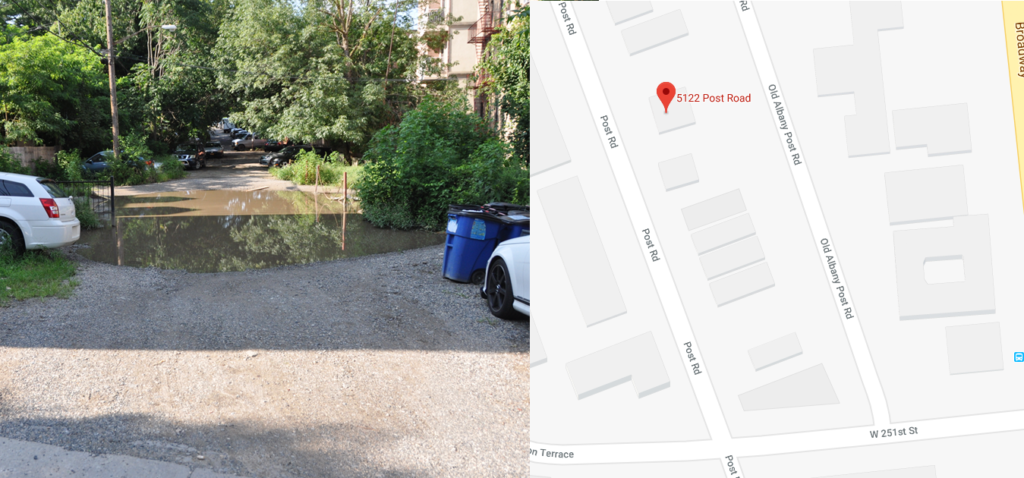

If you were to drive down Post Road in Riverdale between W. 251st and W 252nd Streets, you probably wouldn’t notice anything out of the ordinary–telephone lines overhead, small densely-packed homes with small yards, vinyl awnings, and the kind of brick row houses that you see all over The Bronx. But if you were to slow down to study the buildings as you went by, one would seem out of place. The home at 5122 Post Road, with its rough stone center and its elegant but simple wooden wings, looks nothing like any of the houses around it.

I first became aware of the house from a photo in Reverend Tieck’s Riverdale Kingsbridge Spuyten Duyvil. Tieck’s caption to the photo includes this curious and fuzzy description: “The original or left-hand portion of the edifice supposedly dates from about 1765, although there are claims that it antedates the Van Cortlandt Mansion, which was started in 1748.” I find these sorts of unattributed claims in the passive voice unsatisfying. Like the rest of his book, this caption contains no references or footnotes. So, there’s no way to know where that 1765 date comes from nor do we know what underlies the claim that the house predates the Van Cortlandt Mansion. But if it could be proven that the house is older than the Van Cortlandt house, it would win the title for the oldest house in The Bronx. I sensed the potential for a newsworthy discovery. Considering that Tieck was writing before Google and before libraries started publishing their collections online, I was confident I could solve the mystery of whether 5122 Post Road is the oldest house in The Bronx.

"there are claims that it antedates the Van Cortlandt Mansion. . . started in 1748."

What would simple web searches reveal? The first hit that pops up is a short article hosted on “Forgotten New York” that turns out to contain some dubious information. One thing it gets right is that the home is known as the Hadley House owing to its occupancy by William Hadley and his family. But as I dug deeper, I learned that the home predates the ownership of the Hadleys and that it was a witness to a local form of feudalism, the shame of slavery, the violence of the revolution, and the development and urbanization of The Bronx.

Where the Hadley House stands is just beyond the boundary of the affluent and privately-owned neighborhood of Fieldston. The style of the house is not out of place with the sort of homes that you find in Fieldston–and that’s not a coincidence. Additions were built to the house in 1915 according to the plans of notable architect Dwight James Baum, who lived in Fieldston and designed many of its landmark homes. Much of the later history of the house is revealed in the Landmark Preservation Commission’s report written by Gale Harris in 20001. The report states how Major Joseph Delafield’s 1829 purchase of the house and surrounding farm paved the way for the development of Fieldston as a neighborhood. The surveyor’s map reveals the shape of farm and the various oak and hickory trees, stumps, and brooks that marked the boundaries of the property. The commission’s report and others2 contain fascinating information on the home’s 20th century history.

The power of a tenant mob was the renters' ace in the hole.

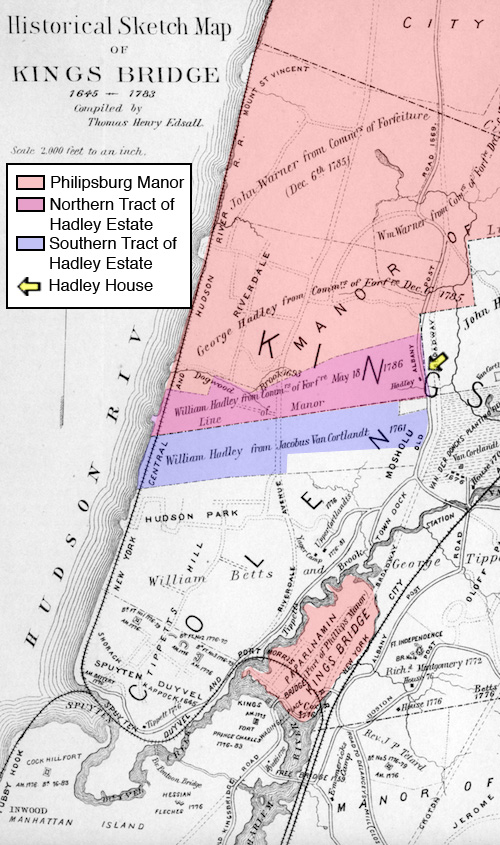

But delving into the home’s early history, the landmark report notes that the property surrounding the house was composed of a northern tract and a southern tract that were acquired separately by William Hadley. The house itself sits on land that was part of the northern tract, which belonged to Frederick Philipse before it was purchased by the Hadleys. The property was once part of Philipsburg Manor, which, along with title of “Lord of the Manor,” was granted to Frederick Philipse by King William in 1693. Philipsburg Manor stretched all the way from the Croton River to the Spuyten Duyvil Creek,3 encompassing an area in Westchester and The Bronx over 4 times the size of Manhattan. By the time of the American Revolution possession of the manor and the title of “Lord” had been passed to Frederick Philipse III. If you were a renter on the manor, tenant-landlord relations were simple. Your landlord was literally a “Lord,” with the power to pass his own local laws and hold his own local court. Your Lord would be very high up in the government and you, very likely, did not meet the property requirement for voting rights. Even if you owned enough property to vote, you would do so by show of hands, often in the presence of your “Lord.” So, it was in your interest to vote with your landlord to stay in his good graces. But the power of a tenant mob was renters’ ace in the hole, which usually mitigated the imbalance of power (early in the 18th century the tenants of Philipse’s upper patent played this card). Unfortunately for Frederick Philipse III, he was branded as a loyalist early during the revolution and all of his lands were confiscated by the new American government under the Commission of Forfeiture.4 That commission sold off Philipse’s lands when the war was over. It was then, in 1786, that the northern tract of the Hadley farm, containing the house, was purchased by William Hadley.5

William Hadley had purchased the southern tract of his farm much earlier in 1761.6 Like the northern tract, this property stretched from the Albany Post Road on the East (close to today’s Broadway) to the Hudson River on the West. The two combined tracts (northern and southern) formed a lot of over 257 acres.

"ninety two and a half acres more or less as the same was formerly possessed by Isaac Green"

The previous owner of the northern tract, Frederick Philipse III, did not do much farming despite owning a manor of more than 52,000 acres. Instead he padded his fortunes by leasing out his land to tenant farmers. The northern tract of the property (including the house) was rented by such a tenant farmer named Isaac Green. We know this from the documents produced by the Committee that seized Philipse’s property. These records indicate that William Hadley purchased “ninety two and a half acres more or less as the same was formerly possessed by Isaac Green.” So if Isaac Green was the previous inhabitant of the house and land, what can we learn about him? Could he have built the house before 1749–making it the oldest house in The Bronx?

Butter Churn, Spinning Wheel, 4 cows, 3 plows, 2 children...£38

I was unable to determine when Isaac Green moved to the area or where he came from. But from a scattered assortment of records, I did learn that he had been paying an annual rent of 5 pounds, 10 shillings to Frederick Philipse III for the property.7 Green married Frances Emmons,8 the daughter of a neighbor down the Post Road, and the couple had four children.9 Isaac’s brother may have lived with him10 in the house as did another family–the slaves of Isaac Green.11 According to Isaac Green’s 1785 estate inventory there were five enslaved people living at the house–a “Negro Man George” and “Harry,” who were valued at 10 pounds. There was also a “Negro Wench Hannah & 2 Children.” The inventory coldly values the older child at 10 pounds and the youngest 5 pounds. No doubt the enslaved people did much of the hard labor on the farm, which boasted a pair of oxen, 4 cows, 2 horses, 3 plows, a spinning wheel, a butter churn and wash tubs. This family of enslaved people was part of surprisingly large Black community that existed in parallel to white Kingsbridge. Green’s estate inventory suggest that despite being a tenant of the “Lord of Philipsburg,” he prospered nonetheless, with the means to acquire a “Woman’s Hunting Saddle,” a “Sconce Looking Glass,” a “Curtain Bed,” and a “writing desk.” It seems that in this part of Philipsburg Manor, a tenant farmer could make a very good living.

At the time that the above estate inventory was taken, William Hadley–together with his family and his slaves–lived just to the south of the Greens on the Albany Post Road on the southern tract. Along with the Greens, they were residents of an area called either “Kingsbridge” or “South Yonkers”, or sometimes “Little Yonkers.” At that time, the neighborhood was part of Westchester County. It was mostly a rural farming community–but it did have a few amenities. There was a local gathering place–Cock’s Tavern–run by John Cock (at today’s 230th Street and Broadway). William Hadley operated a blacksmith shop. There were mills on the Van Cortlandt plantation, which undoubtedly serviced the local farms. It was a tightly knit community of people, many of whom were related by blood or by marriage to the earliest settlers that arrived 100 years earlier. Most of the existing documentation related to Isaac Green and William Hadley pertains to the tumultuous events of the Revolutionary War. That was a period that would tear the community apart and subject the neighborhood, and the Hadley House, to outbursts of violence.

"they feared everybody whom they saw, and loved nobody . . ."

Given the financial success that a mere tenant farmer could enjoy in times of peace, the farmers of Westchester tended to be conservative politically and, on the whole, were not itching for bloody rebellion. However, after the first battles of Lexington and Concord, the neighborhood was swept up in events. William Hadley was part of a committee charged with forming a militia company for South Yonkers. The company was composed of 64 men including Isaac Green, William Hadley, and three other men named Hadley. The tavern keeper, John Cock, was elected captain. The neighborhood’s choice of captain didn’t sit well with the Hadleys or Isaac Green, who together accused him of harboring counter-revolutionary sentiments and of having “damned the Continental Congress.” John Cock’s supporters accused the Hadleys and Green of being motivated by “spite and malice.”12 In this case Isaac Green and William Hadley were right to suspect John Cock’s commitment to the revolution. In 1776 the tavern-keeper and would-be captain undertook a secret mission on behalf of the British. He was sent to retrieve the stolen gilded head of King George III (severed from the rest of his body when a patriot mob tore down the equestrian statue of the monarch at Bowling Green). The revolution had barely begun and the neighborhood was already splitting into different camps. The revolution would go on to fracture families and force many to flee the area.

In 1775 the patriots anticipated an attack on New York and fortified the city and surrounding areas including Kingsbridge. The patriot camp at Kingsbridge numbered in the thousands and there is no doubt that many of the homes in the neighborhood were used to quarter officers. I have read that Washington stayed at the Hadley House but evidence to back up the claim is elusive. But while the patriot army was encamped in Kingsbridge, Washington frequently admonished his own troops in official orders for plundering local farms–ripping down fences for firewood, stealing valuables, etc. It was the beginning of what would be a very rough 8 years for the people of the neighborhood. When the patriots fled, the neighborhood was in British hands and locals were obliged to house British and Hessian soldiers. At other times neither army controlled the area as roving bands and scouting parties of the respective armies, known as “cowboys” and “skinners,” raided local farms and abused the inhabitants. A patriot chaplain, Timothy Dwight, was stationed in Westchester and described the area and its inhabitants as:

Exposed to the depradations of [both the cowboys an skinners]. Often they were actually plundered; and always were liable to this calamity. They feared everybody whom they saw; and loved nobody . . . Fear was, apparently, the only passion by which they were animated . . . Their houses in the meantime, were in great measure scenes of desolation. Their furniture was extensively plundered or broken in pieces. The walls, floor and windows were injured both by violence and decay; and were not repaired because they had not the means of repairing them, and because they were exposed to repetition of the same injuries . . . Their cattle were gone . . . Their fields were grown with a rank growth of weeds and wild grass.

Positioned on west side of the Albany Post Road, the Hadley House saw bands of cowboys, skinners, and sometimes entire armies march past its front door. There are too many occasions to list when the armies traversed the county on the Albany Post Road. One example would have been August 6, 1781.12 On that day, Washington rode by the house on his way to Kingsbridge with “strong detachments of cavalry and infantry” in order to conduct reconnaissance on the British in Manhattan.

"They captured a double post which fired a salvo at them, slapped one of [the] drunks in the face, and left him, taking only a horse."

But the house was not just a witness to troops on the move, but the scene of bloody action during the war. A violent incident occurred around the home during a particularly dangerous time in Kingsbridge–late in 1778–when several accomplished officers patrolled Westchester for the British. Under their leadership, the British clashed all over Westchester with the troops of a French officer fighting for the patriots–Armand Tuffin, Marquis de la Rouerie (a.k.a. Colonel Armand). He commanded a unit of cavalry and infantry that operated out of a base in Tarrytown. On October 11, 1778, just before both armies garrisoned at their winter quarters, Colonel Armand launched a daring attack on a Hessian post that was based at the Hadley House and another house in the area.13 The post formed a picket guard meant to provide early warning of an attack on the British camp at Kingsbridge.

Armand launched his raid under cover of darkness with 20 of his cavalrymen in the vanguard while the infantry stayed behind in a reserve role. The horsemen encountered a single Hessian sentry on the Albany Post Road positioned just north of the house and they managed to take him as a prisoner without alerting the rest of the Hessians. Then Armand’s cavalry charged to the Hadley house “screaming and shouting.” As they approached the house the horsemen received a volley of fire from the Hessian soldiers, who attempted to retreat to the main camp. According to Armand, they had taken more than 12 Hessian prisoners and “give’d to them with the sword.” Apparently, they also took the opportunity to humiliate the Hessians, “Because the . . . picket was drunk and not alert.” The Frenchmen had a little fun with situation and “slapped one of [the] drunks in the face” as they delivered a “sound drubbing.” The alarm was sounded in the nearby camp in Kingsbridge, where the British had a large garrison of soldiers. Two units of mounted troops, the Hussars of the Queens Rangers and Emmerich’s dragoons, were sent in pursuit of Armand’s men as they raced back to their base at Tarrytown. Armand was forced to leave most of the prisoners behind in order to escape their pursuers. However, they did manage to carry away three horses, guns, and two prisoners.

It is unknown if the Greens or the Hadleys were living in the neighborhood at the time of the incident as some of their patriot-leaning neighbors fled the area while it was under British control. But the attack left an impression on the residents of the neighborhood–and on the Hessians, who were so “ashamed” by the incident that the picket guard was placed under arrest.

Isaac Green died from unknown causes at the end of the war and his wife, Frances, died sometime before 1789.14 This left the Hadley House available for purchase by William Hadley in 1785. Hadley lived in the house and had a large family–including son, George Washington Hadley–with his wife, Elizabeth. Also living at the property were at least 6 different enslaved people: Hester, Peter, Nickalus, Samuel, and Magdalene, and one other unnamed person. Peter and Nickalus are listed at a value of $300 on the 1802 estate inventory of William Hadley15–his most valuable “possessions” according to the inventory. Perhaps their value as laborers indicates that these men were able to work as blacksmiths–a possibility given that this was William Hadley’s occupation.16

But the existence of the Hadley house during the revolution was never really in question. It was depicted in several wartime maps (labeled “Green,” for Isaac Green). The question is how far back does the house go before the revolution and could it predate the 1749 date of construction of the Van Cortlandt mansion. It is unlikely that Isaac Green rented the farm for very long before the revolution. There are no records of him living in the area in or before the early 1770s. Additionally, his children were still minors in 1789. This suggests that Isaac Green died relatively young and therefore may not have even been alive when the Van Cortlandt Mansion was built. That still leaves open the possibility that the Hadley House had a previous tenant, prior to Isaac Green. This possibility is suggested by the post-war testimony to of Frederick Philipse III, who stated that his entire manor had been leased without vacancies for 20 years before the revolution. And according to the landmark designation report, the “massiveness of the masonry” and the framing of the house suggest ” an early eighteenth century date” of construction. The scant documents left behind by the Philipse’s give few clues as to who may have occupied the home before Isaac Green. A 1760 rent roll of tenants of Philipsburg Manor should contain the name of a possible earlier tenant, if there was one, but it is organized alphabetically, not geographically. There is no way to know if any of the tenants listed on rent roll lived in the Hadley house. Land deeds for purchased properties were filed with the county clerk of Westchester but leases were not so legal records do not exist in the archives for an earlier tenant.

Perhaps an earlier map could provide information about who may have lived there before the revolution? Unfortunately, it is virtually impossible to find maps made between 1700 and 1775 depicting this part of The Bronx. I did find one map from 1763 which seems to indicate several buildings along the Albany Post Road in the same area. One of these structures could be the Hadley House but the rudimentary detail makes it impossible to know for sure.

Quite often land deeds would describe the boundaries of a property in relation to its neighbors. But all available land deeds for adjacent properties describe the land as belonging to Frederick Philipse without mentioning the presence of a tenant. The land deed records of Westchester County turned out to be another dead end.17

This leads me to the frustrating conclusion that unless some new evidence comes to light, we will never know the exact age of the Hadley House. The Van Cortlandt Mansion retains the title of oldest house in The Bronx. Even with the improved accessibility of deeds, maps, military documents, genealogical records, and online books, I can do no better than William Tieck’s statement that “there are claims that it antedates the Van Cortlandt Mansion.” But while a discovery along those lines would have been welcome, knowing when a house was built is not ultimately what makes local history interesting. What truly sparks the imagination is what is learned along the way–discovering Nickalus, Hannah, and the other enslaved people that lived in the house and wondering what their lives were like and what became of them. Or picturing a troop of French cavalry charging terrified drunken German soldiers on what is now an ordinary Bronx street. Or thinking about what inspired common people to organize a neighborhood militia to fight their own very powerful government. Like the origins of the house, these are questions that cannot be answered with any certainty. The fact that so much of the story of the neighborhood is not only unknown but actually unknowable, keeps new discoveries within reach and others always relegated to the realm of imagination. This inevitably leads to questions, which allow for adding to the story of Kingsbridge, Riverdale, and Spuyten Duyvil.

Notes:

Rather than make an already long article even longer, I am including references and additional information here. Some of it might be useful to genealogists or readers looking to learn more about the architecture of the house. Special thanks to Patrick Raftery at the Westchester County Historical Society and Jackie Graziano at the Westchester County Archives for their help finding documents. All of the resources I used to describe the skirmish between Armand and the Hessians are included below in note 13. Feel free to comment below:

1 – Hadley House Landmarks Preservation Commission Report

2 – Article by David Bady on Lehman College’s Bronx Architecture site provides detailed information on the architectural history of the house.

3 – In the area of Kingsbridge, Philipsburg Manor was not contiguous. His land adjacent to the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, on the tidal island of Paprinnimen, was not connected to the rest of the manor to the north.

4 – Documentation related to the Commissioners of Forfeiture Proceedings. Like so much of the early historical documentation of the neighborhood, this is kept at the Westchester County Archives.

5 – Documentation of William Hadley’s purchase of the northern tract of the property (formerly owned by Frederick Philipse III). It is on the second half of the page and it is transcribed below.

6 – This 1761 deed was very difficult to track down. It is an oversized manuscript at the Westchester County Historical Society so it is not listed in the online database of Westchester County deeds (which is another great resource for studying the early history of the area). Other than the land, the deed includes a “Dwelling house.” This is probably where the Hadleys were living before purchasing “The Hadley House” that they occupied after the revolution. There does seem to be a building indicated on this property on some of the earlier maps from the revolutionary war period. The fact that it does not exist on later maps leads one to believe that the house was destroyed during the war, like so many others in Westchester. Curiously, the deed refers to the land in question as being “formerly laid out to the heirs & assigns of John Betts deceased.” John Betts was the son of William Betts, one of the original 17th century settlers. John Betts’ son, Joseph, lived to the south of the eastern edge of this property and his widow, Abigail, is mentioned in the deed as owning the notch of land that was excluded from the deal in the southeast corner of the property. I was unable to track down how the land found its way into the hands of the Van Cortlandts. The deed also reveals that William Hadley was a blacksmith by trade, a fact corroborated by the blacksmithing tools listed in his estate inventory of 1802.

7 – This comes from the testimony of Frederick Philipse III, who was trying to recoup his losses suffered during the war by appealing to the British government for compensation. It comes from “Loyalist Claims – Transcript of the Manuscript Books and Papers of the Commission of Enquiry into the Losses and Services of American Loyalists held under Acts of Parliament of 23, 25, 26, 28, and 29 of George III.” Volume 41. p. 585. This is a microfilm at the New York Public Library.

8 – New York Wills, Vol. 34, 1780-1782. p. 651.

9 – New York Wills and Administrations, Vol. 39-42, 1786-1799, p. 247 microfilm frame 316

10 – William Green is listed alongside Isaac Green on the roll for the South Yonkers company of Westchester County militia. William Green took the inventory of Isaac’s estate in 1785 following Isaac’s death. According to an interview with Augustus Cregier by John MacDonald, William Green also served as a local guide to an elite infantry unit of patriot soldiers as they moved from Bedford to Kingsbridge on July 3, 1781 for an attack on British positions (McDonald Papers pp. 374-5).

11 – Albany County Administration and Inventory, 1776-1825, Craig-Green, 725-729

12 – Often, when we think about the American Revolution, we imagine the participants’ motivations as ideological and pure but spite and malice played a role as well. In some cases a tenant, such as Isaac Green, might pick a side out of hatred of a landlord, who was with the opposing faction. John Cock may have been close to Frederick Philipse. In addition to overseeing one of his more valuable properties, the inn at Kingsbridge, we learn from the MacDonald Papers that John Cock was Philipse’s personal gardener during the war. Both Philipse and John Cock spent most of the war in British-held New York City. Edsall, Thomas H. History of the Town of King’s Bridge: Now Part of the 24th Ward, New York City. Privately Printed, New York City, 1887. p. 22.

12 – Letter from David Humphreys to Thomas Pickering, August 5, 1781. Also, Memoirs of Major-General Heath, p. 295.

13 – The synopsis of the skirmish at the Hadley House was pieced together from a number of accounts, which contain a good deal of variation between them. Full citations of sources are at the end of this note:

Colonel Armand, in a letter to Washington dated October 12, 1778 wrote the following (keep in mind Armand would very much want to depict his exploits in the best possible light to the Commander-in-Chief):

i have been to day with twenty dragons, near fort independant, where i have surprised the piquet of the hessians, i have take[n] three horses and cary two prisoners at my quarter. one was taken before we Came to the piquet, and the other in the midle of the piquet, with his arms. we take more than twelve, but as the reasort of the enemy did Come upon ou[r] right and left, and had great many horses, and we were ready engadge’d with the second post, we could not cary thoses men, till a place of security without the gretiest danger for our retraite. we took only their arms and give’d to them with the sword. one of the horses which i have tak[en] did belongs formerly to one toris which Caried him to the cam[p] of the enemy, the two others are dragons germains horses. one has bredle and sedle the other, has only his bridle. if had not been a deep wather wich i did not know, i had took many officers, and specially the cnl [colonel] who has the Comand of that post. i must tell you how glad i am to have see[n] our dragons behave with the gretiest couradge in that occasion so fine and proper to desert. my volountaires and officers behaved the same.

Compare the above to the Hessian accounts. The first comes from the diary of Carl Philipp von Feilitzsch, who was a Lieutenant in the first Ansbach-Bayreuth jaeger company. His unit was based at a camp at the south end of Spuyten Duyvil Hill.:

The 12th – The weather improved, but was terribly cold. Toward noon a large enemy patrol approached. Because the non-commissioned officer’s picket was drunk and not alert, it was fired upon. The cavalrymen drove the picket back. We feared they would enter the camp, they had approached so cleverly. They captured a double post which fired a salvo at them, slapped one of [the] drunks in the face, and left him, taking only a horse.

Another Hessian officer, Johann Carl Philipp von Krafft, who was stationed at Frederick van Cortlandt’s house near today’s 238th Street and Waldo Avenue wrote:

11 Oct. Sund. At noon some Rebels unexpectedly rode up from Courtlandt’s House and finding our outposts, to wit, a mounted Yager who had dismounted and a foot-Yager, both asleep, stripped them of their weapons, gave them, in derision, a sound drubbing and them let them go, but without horse or arms. The Rebels then ran off again. Our whole camp took the alarm, the Rebels were pursued but were fortunate enough to escape, thus leaving us ashamed at the affair and at leisure to cogitate over it. The two out-posts, understanding how to excuse themselves very cleverly, were punished with only a few days’ arrest.

So far, all accounts indicate that Armand’s cavalry surprised the inalert Hessian picket guards and beat them up. They also all state that the main camp was genuinely concerned about an attack and that the attackers were pursued. Differences arise in the number of prisoners, casualties, and booty. Armand claims to have “give’d to them with the sword,” but none of the Hessian accounts mention deaths or severe injuries.

Hessian Jaeger Captain Johann Ewald did not describe the attack in his diary but alludes to it in a later entry. Several days after the attack he was sent to meet with Patriot General Scott to discuss a prisoner exchange although he secretly hoped to gain intelligence on the location of Colonel Armand’s base “in order to square our accounts by a trick against [him].” Ewald writes of his meeting with Armand.

Colonel Armand arrived with six officers and an escort of twelve dragoons. I was received with the utmost politeness . . . I gave him my letter [requesting a prisoner exchange] and we joked quite friendly about the last trick which he had played on the jager picket, and I invited him to risk the affair once more.

Despite the bravado, you get the sense that Armand managed to pull off an impressive feat with the raid.

More information on the skirmish comes courtesy of John MacDonald, who directly names the Hadley House as the scene of the attack. Between 1844 and 1851 an elderly MacDonald traversed the Westchester countryside meeting with 241 different people for 407 interviews about their memories and experiences of the Revolutionary War. The recorded interviews are held at the New York Historical Society with a copy at the Westchester County Historical Society. MacDonald used information gleaned from the interviews, in addition to his own research, to deliver presentations at the NYHS. In 1851 he presented on Colonel Armand and described this attack “upon the outpost of the Green-Yagers, situate at Hadley’s house, on the north river post-road.” These presentations and some of the interviews were published by the Westchester County Historical Society.

MacDonald was informed in some part by the testimony of Augustus Cregier, who remembered the incident. Augustus Cregier lived in today’s Van Cortlandt Park with his father, Dr. John Cregier, in a house owned by the Van Cortlandts. MacDonald’s notes from his interview with Augustus say “Colonel Armand . . . surprised the picket guard of Col. Worm, about half a mile north east of Frederick Van Courtland’s and north near which Mr. Garret Garrison in now lives.” At the time of the interview, William Hadley was deceased and the Hadley House and lands were sold by his heirs. Garret Garrison lived adjacent to the property on its southern boundary. Cregier is pointing to the area around the Hadley House as the scene of the attack.

Citations for the Hessian diaries and McDonald Papers:

Feilitzsch, Heinrich Carl Philipp von, and Christian Friedrich. Bartholomai. Diaries of Two Ansbach Jaegers. Translated by Bruce E. Burgoyne. Heritage Books, 2007. p. 47.

von Krafft, John Charles Philip. “Journal of Lt. John Charles Philip von Krafft, 1776-1784.” Translated by Thomas Henry Edsall. New York Historical Society Collections for the Year 1882, vol 15, 1883. p. 66.

Ewald, Johann. Diary of the American War A Hessian Journal. Translated by Joseph P. Tustin. Yale University Press, 1979. p. 152.

MacDonald, John. “The Life and Character of the Marquis de La Rouerie (Col. Armand), Including an Account of His Services During the American Revolutionary War.” The McDonald Papers – Part II. Publications of the Westchester County Historical Society, vol 5, 1927. pp. 19-20.

14 – This comes from the will of Abraham Emmons–a relation of Frances Green, wife of Isaac. New York Wills and Administrations, Vol. 39-42, 1786-1799, microfilm on ancestry.com slide 316. The deceased couple left behind four orphaned children.

15 – The estate inventory of William Hadley can be found at the Westchester County Archives among a large collection of estate inventories.

16 – A descendant of William Hadley has done some research on the enslaved people that labored for the Hadleys. Her findings are here. It is worth noting that the Black people she found on the census are from one of the very few Black households in the area at that time. The vast majority of the Black population left the neighborhood after they were gradually emancipated.

17 – While I did not find a tenant of the house before Isaac Green, I did find a suspicious deed that caused me to wonder about that possibility. It is a deed from Samuel Betts to Jacobus Van Cortlandt dated 1714 (Liber G p. 250). Samuel Betts was a descendant of one of the original settlers in the area, William Betts. All of the land adjacent to the Hadley House that was not owned by Frederick Philipse was owned by someone in the Betts family. The southern tract of the Hadley farm once belonged to the heirs of John Betts. The land to the east was once in the hands of Joseph Betts. The Hadley House and property was like a wedge sticking into Betts land. The preamble to the deed reads: “TO ALL WHOM THESE PRESENTS SHALL COME, SAMUEL BETTS, of ye Yonkers, in ye Manner of Philipsburg, in ye County of Westchester in ye Collony of New York, Yeoman, and ELIZABETH, his wife, Sends Greeting.” The deed indicates that Samuel Betts was living in Philipsburg Manor and Yonkers. Could Samuel Betts have been a tenant living in the Hadley House, which was both within the confines of Philipsburg Manor AND in “ye Yonkers?” There is no way to know for sure given the available evidence. It does, however, seem likely that if Samuel Betts were to live anywhere in the Manor, it would have been close to all of his family in Kingsbridge–most of whom lived around today’s Van Cortlandt Park. If he wanted to stay close to family, he could not get closer than the Hadley House.