Colendonck and the Youncker's Plantation

Two 17th-Century Colonial Settlements in today's Van Cortlandt Park

Nick Dembowski – 6/27/2023

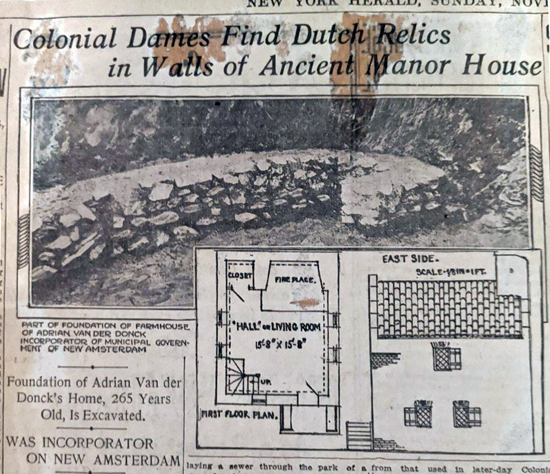

The Mystery of the Building Foundations in Van Cortlandt Park in The Bronx

While digging a trench just south of the Van Cortlandt House Museum in 1910, a construction crew struck a large hard stone object 10 feet below the surface. Further excavation revealed an ancient-looking building foundation among scattered artifacts: a silver button, Delft china fragments, a Dutch pipe. The New York Herald proclaimed: “Foundation of Adrian Van der Donck’s Home, 265 Years Old, Is Excavated.”2 But according to another published history, several years earlier as park workers were leveling out a field hundreds of feet to the east, foundations of “Van der Donck’s farmhouse” were allegedly discovered among broken Dutch pottery, jugs, and wine bottles.3 And according to yet another history produced by NYC Parks, Adriaen Van der Donck’s farmhouse was uncovered west of the Van Cortlandt House Museum.4 How could the building foundations of one colonist’s farmhouse have been discovered at least three different times in three different places?

Colendonck, the First Colonial Settlement

Right: Presumed portrait of Adriaen Van der Donck, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., online collection

Since multiple 17th century building foundations were found in Van Cortlandt Park, it is worth exploring if Van der Donck had neighbors living near his home on Colendonck. If it were up to him, there would have been plenty of other colonists living at his settlement. After all, he referred to his land as a “colony” and his grant came with an obligation to fill his land with settlers. Documents written before his death in 1655 indicate Van der Donck worked to fulfill this obligation. While back in the Netherlands, Van der Donck attempted to bring 200 colonists to New Netherland including 100 farmers. And while that attempt was not successful, he did at least manage to recruit a tile maker, a barrel maker, a gardener, and carpenters to accompany him.9 Presumably all of these workers were employed to help develop Colendonck. When Van der Donck’s wife and extended family set sail for New Netherland, they too brought along additional colonists hired by the family.10

Above: John Ward Dunsmore’s interpretation of the 1655 attack on Colendonck. Painted for the 1916 Title Guarantee and Trust Company calendar.

Documents written shortly after Van der Donck’s death confirm that Van der Donck and Mary, his wife, were not alone at the settlement. In November of 1655, documents from New Amsterdam’s orphanage refer to three recently deceased men, Jan Mewes, Evert Jansen, and Jan Gerritsen, who were “living at Verdoncx.” The entry noted that they perished in the “late disaster,” which is surely a reference to the 1655 raid on Colendonck.11 In January of 1656, a paper was presented to Peter Stuyvesant stating that a native Wiequaeskeck man was working at Colendonck to look after Van der Donck’s cows.12 And a statement provided to the court of New Amsterdam by Mary Van der Donck refers to a pair of bibles belonging to Catalyntie Verbeeck “which the Indians took from Ver Doncks house.”13 If Verbeeck’s bibles were in the Van der Donck house, perhaps she was also living at Colendonck. And In 1667, “Ytie Hendricxsdr” appeared before the magistrates of Albany and declared that she was one of three sisters that was “taken prisoner by the Indian barbarians on the land of Van der Donck on the east side of the [Hudson] River.”14 Perhaps the Hendricks sisters were living with their family somewhere near the Van der Donck household. Even with just fragmentary records, it is clear that Colendonck was a settlement of multiple individuals and families. It is therefore possible that there were more structures in Colendonck than previously believed in order to house these people.

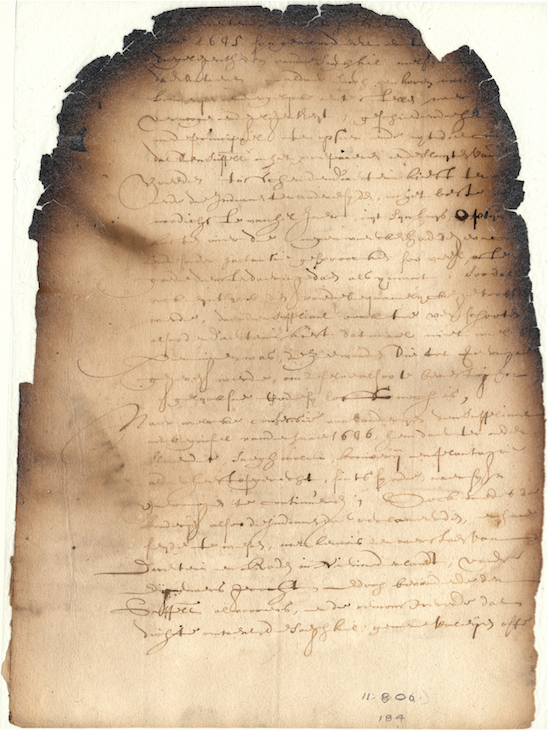

Above: In 1652 or 1653, Van der Donck wrote this petition to the Dutch West India Company that contains valuable information about the Colendonck settlement.

"The Youncker's Plantation," the Second Colonial Settlement

Above: An 1871 map overlaid upon a contemporary Google Map of the Kingsbridge valley with Spuyten Duyvil Hill on the left and Kingsbridge Heights on the right. In 1871 Tibbetts Brook (highlighted in blue) still supplied the brackish water that fed the salt marshes (highlighted in green). These grassy marshes constituted the “meadow” that early colonists desired.

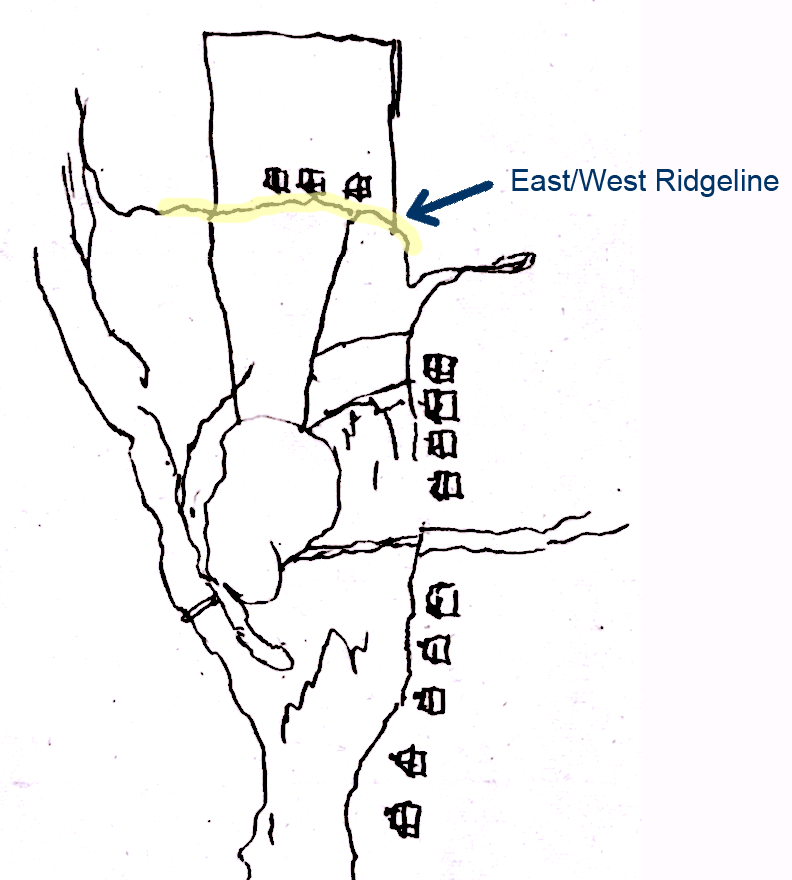

A Ridge for Reference

Above: View looking north/northeast with the Van Cortlandt House constructed 1748-1749, in the distance. This photo (ca. 1900) was taken from the marshy low-lying area to the south of the house, where Tibbetts Brook flowed in the foreground. Notice that the Van Cortlandt House sits on a plateau beyond a ridge. That is the same ridge that was depicted with a heavy line in the “Draught of Fordham and the Meadows” map above. Photo courtesy of Van Cortlandt House Museum/NSCDNY.

Right: View looking northeast with the Van Cortlandt House in the upper left corner. This photo was taken shortly after the creation of Van Cortlandt Park. It gives a clear view of the east/west ridge and the difference in elevation on either side of it. The photo also shows that the ridge clearly has been shaped by people over the centuries to give it a more uniform appearance. NYC Parks photo.

Many postcards from the early 20th century depicted the low-lying area just south of the Van Cortlandt House, which was the location of Van Cortlandt Park’s newly planted “Dutch Garden.” The first one here shows the view looking north. Again, the prominent east/west ridge is in the background. The second postcard shows the same ridge on the right with a westward view.

Since the ridge shows up both in this early map and in today’s park, we can safely say that the three farmhouses of William Betts, John Hadden, and George Tippett were located just north of that ridge in the vicinity of where the Van Cortlandt House Museum stands today. That is the same general area that the multiple 17th century building foundations were excavated in the 20th century. As mentioned, all of those building foundations were attributed to Adriaen van der Donck. But that attribution was made without the knowledge that the three farmhouses of Betts, Hadden, and Tippett occupied the same location only 12 years after Van der Donck’s death. It seems probable that some number of those excavated foundations belonged to the later English colonists.23

At their 1672 hearing, William Betts and George Tippett would not receive satisfaction as the governor’s ruling favored John Archer. But they could take some solace in the fact that their settlement would blossom. Their descendants’ families settled on the north side of the ridge and on adjacent plots. Other colonists moved to the area as well, resulting in a proliferation of home sites, barns, and stables. They had farms, orchards, and cattle, their own community burial ground, a commonage for grazing and for timber, and a “good and Strong” blockhouse for defense. Paths and roads connected their settlement to the nearest mill and other settlements.24 The first mention of an enslaved African presence in the area also appears in this time.25 Land deeds from the period commonly referred to the locality as “the Younkers Plantation in the County of Westchester” in recognition of the “Jonkheer” Van der Donck’s prior occupancy. Samuel Hitchcock, who married into the Tippett family, represented the community in county politics and conducted the area’s first census.26 A dozen years after the dispute with John Archer, the number of structures in the settlement more than doubled. This forgotten settlement was probably the most densely populated part of Yonkers. In 1684 it was mapped again:

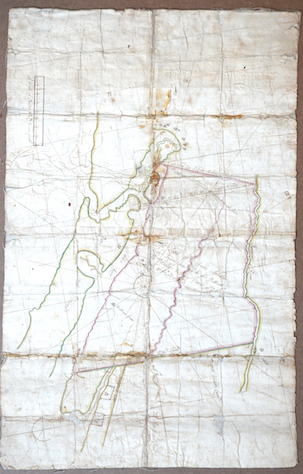

LEFT: The Land of John Archer Layd Downe acording to his Pattent by Phillip Welles surveyd July 6th 1684, 3080 Akers. The Collegiate Churches of New York.

RIGHT: A zoomed in section of the map on the left depicting the 17th century settlement in modern Van Cortlandt Park. Note how the structures are situated north of the aforementioned ridge that is still visible in today’s park just south of the Van Cortlandt House Museum. Here the ridge is depicted as a green line. Unfortunately, this map was torn at some point and when it was glued back together, a portion of it was lost along the seam. It is likely that the map, in its original form depicted even more structures, which are no longer visible on the damaged map.

1693 - Arrival of the Van Cortlandts

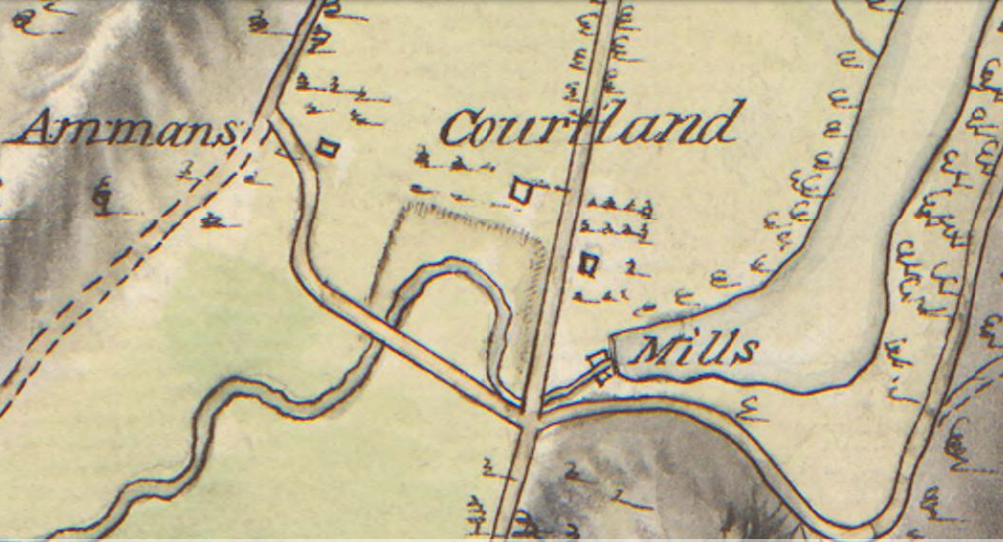

Development and growth continued on the “Younker’s Plantation” through the 1690s but was halted after this land caught the eye of a wealthy New York City merchant, who sought a location for his family’s country estate. In 1693, Jacobus van Cortlandt made his first purchase there. The resulting deed described his purchase as a “dwelling house and orchard . . . att a place called the ould YOUNKERS.”27 It defined the property as bounded to the west by the lot of John Betts. Later, in 1708, Jacobus van Cortlandt purchased the “home lott” of John Betts. That lot is described as bounded on the west by the lot of Samuel Betts.28 As Jacobus van Cortlandt was buying up the home lots of the Tippett and Betts descendants, the corresponding land deeds describe the property boundaries in terms of who owned the adjacent properties. That makes it possible to piece the properties and owners together like a puzzle. When completed, said puzzle depicts a string of houses and outbuildings centered at the southern end of the Parade Ground in today’s Van Cortlandt Park. That corresponds with the depiction in the above 1684 map. It also correlates with the order of names on a census taken in 1698. By combining information from the local deeds, the maps, local wills, and the census, it becomes possible to guess who was living where:

Notes and References:

1 – Map clippings from three different maps are shown: A) Applications for Land Grants, Volume 1, Page 17 of Series A0272, New York State Archives; B) Draught of Fordham and the Meadow [1669] from Minutes of the Executive Council of the Province of New York edited by Victor Hugo Paltsists, opposite p. 195; and C) The Land of John Archer Layd Downe acording to his Pattent by Phillip Welles surveyd July 6th 1684, 3080 Akers. The Collegiate Churches of New York.

2 – New York Herald, Sunday November 9, 1913.

3 – Jenkins, Stephen. The Story of the Bronx from the Purchase Made by the Dutch from the Indians in 1639 to the Present Day. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912, p. 301.

4 – Pons, Luis. Van Cortlandt Park History. Administrator’s Office, Van Cortlandt & Pelham Bay Parks City of New York Parks & Recreation, 1986. p. 4.

5 – As will be shown, details about events at Colendonck are sketchy. Much of what is known comes from one document: a 1652 or 1653 petition written by Van der Donck to the Directors of the Dutch West India Company. That petition still exists in the New York State Archives although it was badly damaged by the infamous New York State Library fire of 1911. Therefore, the most recent translation is missing quite a lot of original text. Thankfully, it had been translated prior to the fire and published on p. 408 of Robert Bolton’s 1848 A History of the County of Westchester, from its First Settlement to the Present Time, Vol. 2. Depending on which translation you look at, you may come away with different conclusions. The most recent biography of Adriaen van der Donck by J. Van Den Hout, which made use of the more recent incomplete translation, suggests that Van der Donck lived on the bank of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, which is not in modern Van Cortlandt Park. However, later land deeds show that this was not possible. When Van der Donck’s brother-in-law sold the land that would eventually become Van Cortlandt Park in 1670, it was described as including as being formerly “in ye possession and occupation of old Youncker van der Dounck.” Whereas Van der Donck’s property on the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, the island of Paprinimen, was gifted to George Tippett on a different occasion.

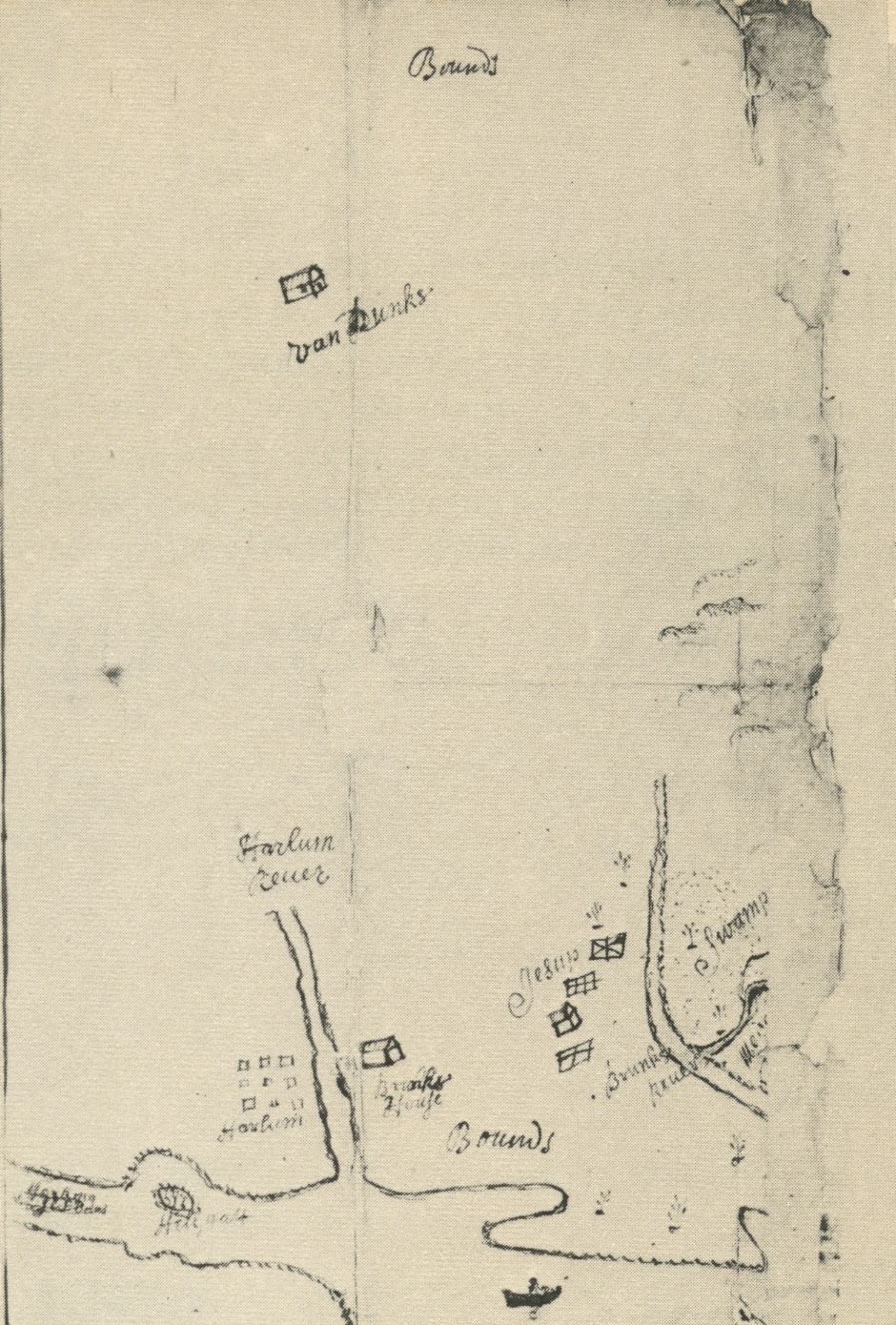

Another early map, when scale is taken into account, gives further indication of the location of Van der Donck’s home. Georeferencing the below map shows that the home labeled “Van Dunks” would have been located in the vicinity of today’s Van Cortlandt Park (although it is frustratingly lacking in detail).

6 – Ibid.

7 – This attack was part of the so-called “Peach War,” in which a force of Susquehannock fighters and their allies attacked the Dutch colony. The attack was motivated by the Dutch conquest of a Swedish settlement that had a trading relationship with the Susquehannocks. There is some evidence to suggest that Van der Donck had good relations with the indigenous people living near Colendonck but it is unlikely that the Susquehannock would have had any idea who he was.

8 – 1652 or 1653 Van der Donck petition. See note #5.

13 – Fernow, Berthold. The Records of New Amsterdam From 1653 to 1674 Anno Domini. Knickerbocker Press, 1897. Vol II p. 8.

14 – Fort Orange Records 1654-1679. translated and edited by Charles T. Gehring and Janny Venema. Syracuse University Press, 2009. p. 422.

15 – Bankoff, H. Arthur and Winter, Frederick A. “The Archaeology of Slavery at the Van Cortlandt Plantation in The Bronx, New York.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Vol. 9, No. 4 (December 2005). p. 294.

16 – Van den Hout. p. 95. As a side note, it does not appear that Van der Donck’s contemporary, Jonas Bronck, utilized slave labor on his nearby farm.

17 – Thomas Henry Edsall, author of the 1887 History of the Town of Kings Bridge, drew a “Historical Sketch Map” of the Kingsbridge area, which depicts three home sites just south of the Van Cortlandt House Museum (labeled 1676). He did not offer any explanation of how he came to determine that there were structures in that location. It is interesting to note that he drew this map before any of the 17th-century stone foundations were found in the area.

18 – Minutes of the Executive Council of the Province of New York. edited by Victor Hugo Paltsis. Vol I, p. 201.

20 – Ibid. p. 211 and beyond.

21 – Ibid. p. 206. Same property that was sold to Hadley in Westchester Deeds B 94.

22 – Will and Testament of William Betts, 1675. He wrote: “I give and bequeath unto my wife Alice Betts, after my decease, my House and House Lott, with the Barne and all the Meadow that is lying by my House Lott, now in Possession; Also one third part of my Land in the Planting ffield within ffence, All which are Scituate in the younckers Plantation.”

23 – It is also entirely possible that Van der Donck’s home, or perhaps its foundation, was repurposed by one of the English colonists that arrived 12 years later.

24 – References to:

- Orchards: Westchester Deeds Liber A, p. 203; Liber B, p. 94; etc.

- Cattle: Westchester Deeds Liber B, p. 90;

- Burial Ground: Westchester Deeds Liber E, p. 147; For additional documentation, see also

- Commonage for grazing and timber: Westchester Deeds Liber B, p. 91; Liber D, p. 13; etc.

- Blockhouse: “Petition of Inhabitants of Yonkers, Praying to be Excused from Joining the People of Fordham in case of an Indian Invasion,” Brodhead, John Romeyn Documents relative to the colonial history of the state of New-York: procured in Holland, England, and France. Weed, Parsons, 1853-1887. Vol. 13 p. 492

- Paths and Roads: Westchester Deeds Liber A, p. 203; Liber B, p. 94; Liber B, p. 114; etc.

25 – Estate Inventory of George Tippits of Younkers by Thomas Huntt, William Hayden, Edward Griffin of Flushing – September 29, 1675. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Van Cortlandts and other local farmers held larger numbers of enslaved people. See here.

26 – “Inhabitants of Fordham and Adjacent Places.” New York Genealogical and Biographical Record Vols. 38-39, New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, 1907. p. 218.

27 – Westchester Deeds Liber B, p. 223.

28 – Westchester Deeds Liber D, p. 13

29 – The 1781 map of the area depicts a house to the west of the Van Cortlandt house labeled “Ammans.” This could be the former home of Joseph Betts. His widow, Alice Betts, married Abraham Emmons. The house to the east of the Van Cortlandt house previously could have been the home lot of George Tippett III, who sold his “home lott” to Jacobus van Cortlandt in 1732 (Westchester deeds Liber G, p.

30 – “Old Indian Relics.” New-York Daily Tribune, December 14, 1890.

31 – Bankoff, Arthur H., and Winter, Frederick A. Van Cortlandt House Excavations 1990 and 1991. p. 10.