Errand Go Bragh

By Edward J. Rogan

Editors note: an excerpt from the author’s unpublished recollections, entitled Memorare.

I suppose it only made sense that, as the eldest, I would be the one who would run (literally) errands for my mother when we lived in Kingsbridge. Truth told, I probably liked it–it made me feel grown-up and responsible.

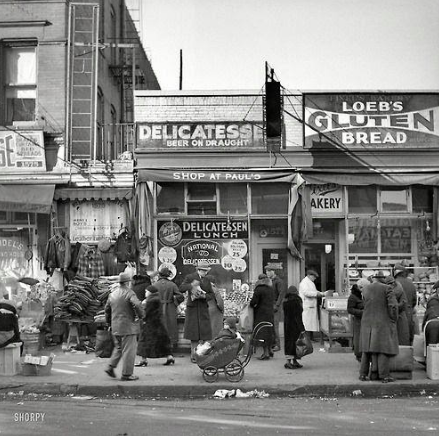

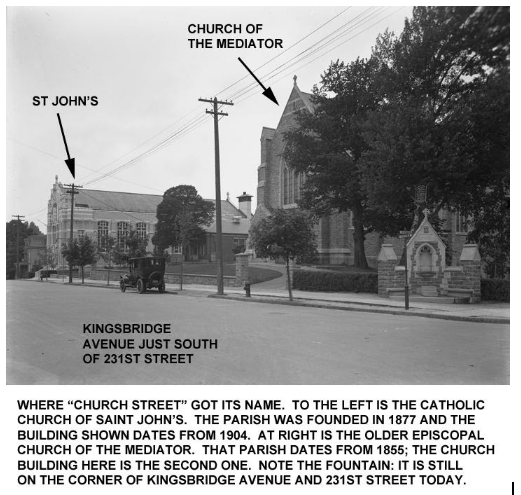

Kingsbridge in the early sixties still had the feel of a small village. Small stores lined both sides of 231st Street from Broadway up to and across Kingsbridge Avenue and down to Corlear Avenue. There were two German delicatessens, a German restaurant, three Jewish delicatessens (all Kosher), a shopfront pizzeria, a wool shop, a shoe store, a Catholic religious goods store, one or two bakeries, Pat Mitchell’s grocery store, a drug store and a soda fountain, among others.

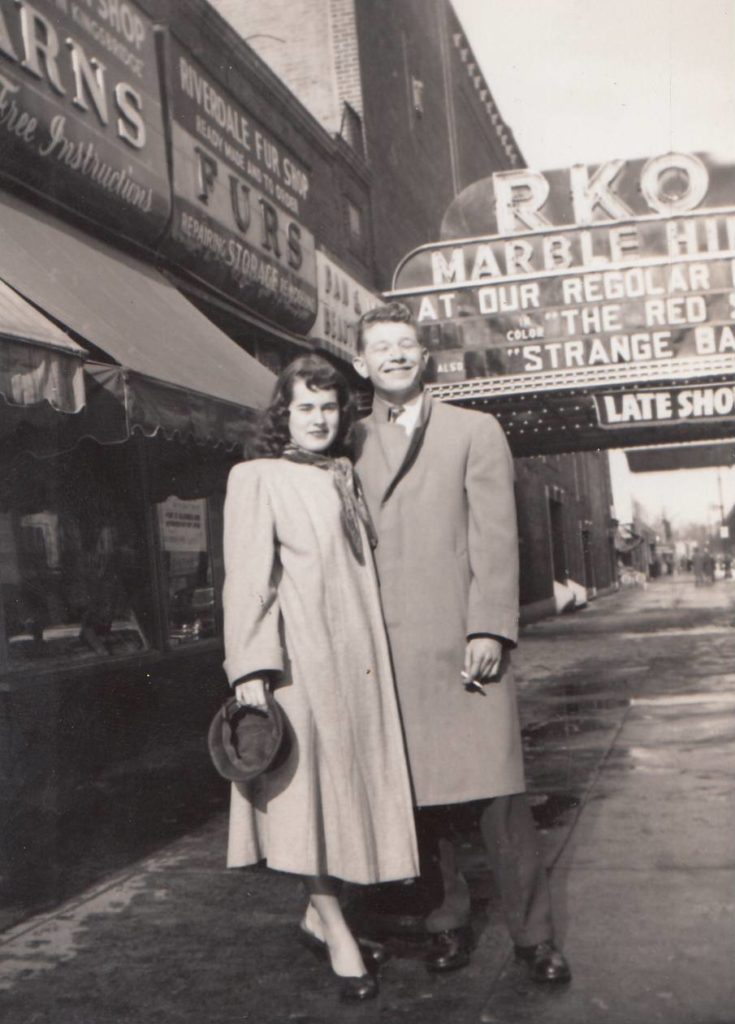

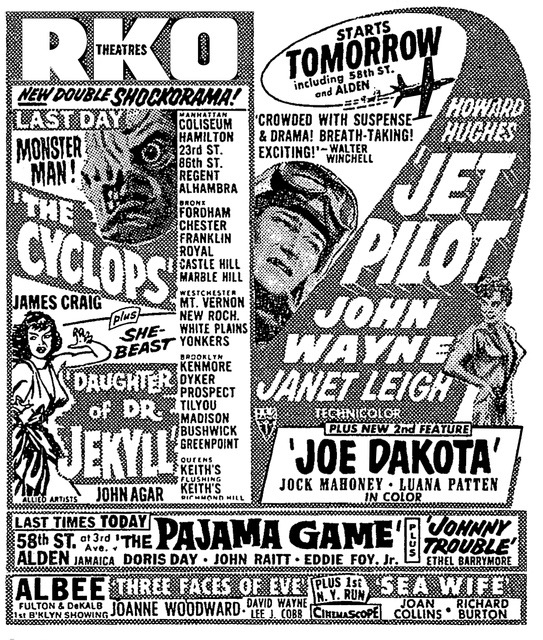

Three large stores fronted Broadway–the A&P grocery store, the Grand Union, and Woolworth’s 5 & 10 Cent Store. Shouldering these were a Tom McAn shoe store, a Singer Sewing Machine and sewing goods shop, and further along, the RKO movie theatre (Radio-Keith-Orpheum). Mary Campion (Mom’s Uncle Joe Marrinan’s wife) worked in a tiny sewing notions store tucked into a side street next to the A&P.

The four corners housed a bank, a news agent, a butcher, and a Horn & Hardart’s automat. The intersection of 231st and Broadway was anchored by the el station which hovered above it like a beach house on stilts – each corner had a set of wrought-iron stairs leading to the somewhat Victorian-looking station and platforms. The station created a dark but cool oasis below on the hottest of summer days, and most of Broadway in that area was likewise shaded by the railway lines above. The pillars supporting the system dotted the roadway below like iron-studded sequoias.

It was a compact village and held just about all that we could need, materially and personally.

The wool shop, for instance: my mother could never quite afford to buy all the wool she needed for making our sweaters at one time — but it was crucial that the skeins all come from the same dye lot. So she came to an arrangement with the wool store lady. Together, they would calculate the number of skeins needed and these would be placed into a cardboard box with Mum’s name on it. This would be placed on the top shelf behind the counter. When she had money Mum would go to the store and buy a skein or two at a time. That way the dye lot was guaranteed. Mum was pretty fit in those days and she often seized a moment when most of us were napping, leaving me in charge, and she would sprint up Corlear Avenue, rounding the massive Corlear Sycamore, up 231st St., across Kingsbridge and down towards Broadway. She bought what she could afford and then reversed the run. Unfortunately, one day she ran smack into her mother who promptly tore a strip off her for ‘abandoning’ her children. From that time on it became my job to go to the wool store to repatriate the stranded skeins. I recall that they cost twenty-five cents each.

There was also a ladies’ shoe store next to the wool shop. They stocked Ena-getic shoes. As a very good speller and something of a purist, I was offended by this mongrelized spelling of ‘energetic’ and no amount of explanations by my harried mother could convince me otherwise. They also carried ladies’ stockings — or nylons as they had come to be known. As a ten-year old, I was mortified when my mother sent me there with an order for a pair of ‘nude’ nylons. I could feel my chest constrict as I steeled myself to utter that word in the shop full of women. Oddly, none of them ever commented.

Friday nights were my favourite part of the week. My father worked as an insurance salesman for the John Hancock Life Insurance Company and part of his job was to go out on Friday nights to collect the insurance premiums – a good thing to do as Friday was pay day. To wait another day or so was to risk not getting the premium or to have it squandered in the local bar. Friday night was also Rawhide night. Mum loved Rowdy Yates (a gloriously young and unwrinkled Clint Eastwood) and wouldn’t miss an episode. Now, my role was critical to the success of our Friday night entertainment. I was to go up 231st St. to Loeser’s Jewish Delicatessen to buy each of us a potato knish (which I have heard described as Jewish food for Irish people). Loeser’s had a window which opened onto the street. I prayed there would not be anyone in line as that would slow me down. The smell of the knishes grew stronger as I approached. They lay on the griddle behind the window. I greeted Mr. Loeser and gave him my order. Mr. Loeser asked after my mother. And my father. And the baby. And my schoolwork, as I fretted about the time. Each knish had to be folded into a wax paper and then placed carefully into a double brown bag (“I’ve seen you run,” Mr. Loeser said, “You should be so lucky not to have knishes schmutzing everywhere with only one bag”!) Then, still conscious of the time, I had to charge back up the street and go to the other Jewish deli because that man made the best pickles anywhere – which I was never to mention to Mr. Loeser. ‘A nickel a pickle’ boasted the sign — and they, like submarines, remained submerged in the cloudy brine of the massive barrel. My job was to get the biggest pickles, get them into wax bags and get this feast home in time for the opening theme song at eight o’clock. We put on our cowboy hats and settled down, ready to belt out the lyrics, finishing strongly with ‘Head ‘em up, move ‘em out – Rawhide!” What a wonderful way to spend Friday nights. It is certainly one of my most vivid and happy memories.

Another favourite errand was anything associated with Fuhrman’s Department Store. Fuhrman’s was a terrific local emporium on 231st Street, just across Broadway across from the movie theatre. Fuhrman’s was jointly owned by the four Fuhrman brothers. To my eyes, Fuhrman had it all – they even had a ‘lay-away’ plan which my mother certainly took advantage of; it had a number of departments including the coyly named ‘Foundations Department’ (the wife of one of the brothers worked as a saleswoman there until she was 93!). Mum would often phone in her order and it would be my job to collect it. But, the best part of a trip to Fuhrman’s was paying for our purchases. Fuhrman’s had what I think was called a ‘Pneumatic Capsule’ system. Bills of sale were written up by the sales staff, money was collected from the customer and both were bundled into a capsule with a screw-on top and placed into a pneumatic tube system which sucked the capsule up with a whoosh and sent it to the cashier’s office high above the sales floor. Moments later the capsule returned – it contained the bill, marked PAID, and the correct change. What a terrific system. I could have watched it all day.

However, not all of my memories associated with errands were pleasant ones. My mother used to send my brother Owen and me up to the A & P for groceries. The Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company used to give out a number of ‘Plaid Stamps ‘to customers based on the amount of money they spent. These would be pasted into books and redeemed for prizes. I enjoyed pasting them into the books for my mother and we certainly did get a number of useful items. However, one day, my mother sent us up to the store with a five dollar bill to buy some items. I can no longer remember how it happened but the five dollars slipped to the floor and was quickly snatched up by a passing teenager. We demanded the return of the bill and when it was refused, we shouted for the store manager but, to our horror, he believed the teen and we were forced to go home with no money and no groceries and, as my mother acidly pointed out, “no bloody Plaid Stamps either!”. Five dollars was a fair bit of money in our household and I’ve no doubt that Kraft Macaroni and Cheese was on the menu consistently that week.

My mother did not consider herself a lucky person. In fact, sometime during the 1980s, when she was living in Toronto, a $12 million dollar Ontario lottery prize was won by someone from her small Irish hometown of Kilkee. Mum was furious. She spluttered and fumed, declaring that the odds of winning, formerly astronomical, were now beyond astronomical — as the likelihood of a second person from Kilkee winning the lottery was incalculable. Consequently, in a fit of pique, she stopped buying the lottery tickets for a considerable length of time.

Still, I recall Mum coming home from her errands one Bronx winter’s day in the early ‘60s gleefully clutching a ten dollar bill in her hand. She had come across it half frozen on the sidewalk on Broadway. She chipped it out of the ice, not quite believing her good fortune. Mum did not share the wealth. Instead, she purchased a Missal with a snow-white leather cover – the perfect fashion accessory for a young Catholic mother at Sunday Mass.

Speaking of Mass, I was pleased to be an altar boy and was proud as ‘a pig with pants’ when I ‘served’ my first Mass. The whole family was there, including my grandparents. I used to serve the 6.30 morning Mass for Fr. Flaherty – it was no hardship for me as I liked getting up early. Many of the altar boys didn’t like Fr. Flaherty. He was crotchety, quick-tempered and inconsistent. (I found out years later that he had brain cancer). But I was always on time, knew my Latin, and could be counted on not to drop anything and, so, he and I got on quite well together. He was also generous with me. After Mass was over and I had helped put away his vestments, he would frequently ask me to run an errand for him – something simple like buying cigarettes or a newspaper. He would reach into his cassock, pull out a palm-full of change and give it to me for the errand. He never counted it. There was always some change coming to him – but he invariably waved it away. This was a significant source of income for a ten-year old – which was used to buy comic books or the occasional treat of a paper cone full of French fries from Woolworth’s.

Times were tough, however, when Dad fell gravely ill. He suffered horribly from kidney stones and eventually his left kidney had to be removed. I do not recall the sequence of events now but the sum of it was that something went awry after the operation and he had already been discharged from hospital. He was in great pain and I remember my Grandfather Crotty carrying my father like a child down the steep sets of stairs to the stoop and the street below — taking him to the hospital in his car. I was certain my father was going to die. However, his condition became better; although he remained in hospital for some time. I have a vague recollection of being told that his blood bill was several thousand dollars – when my mother only earned that much in a year.

P.S. Loeser’s Delicatessen is still going strong after fifty-seven years. I recently read that Fredy Loeser started the delicatessen at the age of seventeen (1961), with monies received for his bar mitzvah. The fox-hunting mural which adorns one wall is the same one I knew as a child. When we went to the old neighborhood around 2002, we went for lunch at Loeser’s. Linda blurted out to Mr. Loeser that I had bought knishes here as a boy in the 60s. Mr. Loeser kept slicing pastrami, never missed a beat, and said,” Nice to see you again” and went on with his work!

You can leave a comment here.