Home › Forums › The Colonial Era › Visitors to the King’s Bridge (#3)

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 7 years, 6 months ago by

ndembowski.

ndembowski.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

September 24, 2016 at 5:41 pm #191

1858 illustration In a sense, the first visitors to the King’s Bridge were the people that built it. You may have heard that Frederick Philipse, Lord of Philipsburg Manor, built the King’s Bridge (the first bridge to connect Manhattan to the mainland). But while Frederick Philipse got his start in New Netherland as a carpenter, he likely had no hand in the bridge’s construction other than providing capital. Then who built the bridge?

Carney Rhinevault, in the very entertaining Hidden History of the Lower Hudson Valley, writes, “the bridge approaches were built by Philipse’s slaves and were made of laid-up stones.” I contacted him to ask where he had acquired this information. He could not remember but said that he “heard it somewhere.” Despite the lack of documentary evidence, this claim seems likely to be true. Philipse held about 40 slaves, some of whom were skilled laborers–millwrights, masons, carpenters, etc. They worked on his other construction projects including the Old Dutch Church at Sleepy Hollow and probably the mill dam for his upper mills.¹ It just stands to reason that slave labor would have been employed in the construction of the King’s Bridge.

Sadly, the bridge’s connection to slavery does not end there. A half century later, after Francis Doughty‘s lease of the bridge and tavern expired, the property hit the market yet again.

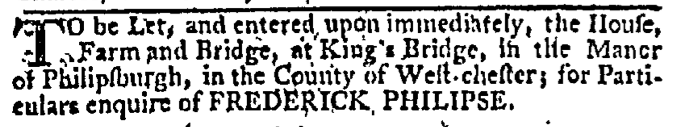

5/14/1759 New York Gazette The 1760 rent roll of Philipsburg Manor does not reveal the identity of the next proprietor but newspaper advertisements seem to suggest James Bernard was next to keep house at the bridge. Interestingly, the inn acquired the name “Bunch of Grapes” at this time.

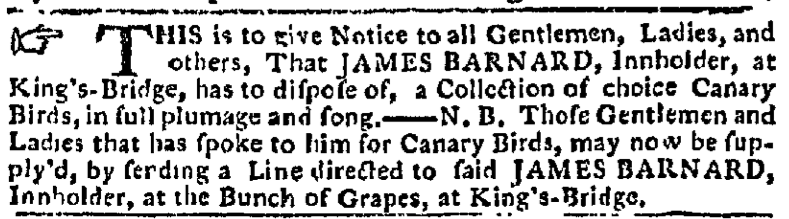

12/3/1764 New York Gazette It is not clear if slave labor was employed in keeping the inn or the bridge. However, the following ad makes it seem likely.

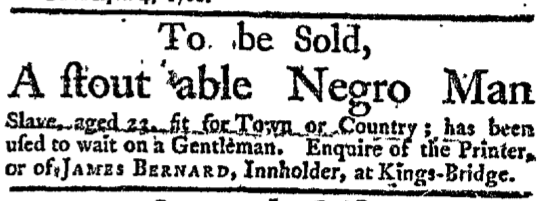

4/26/1762 New York Gazette It could be that James Bernard was not holding the slave but rather just an intermediary for the sale. Another possibility is that Bernard was selling the slave on behalf of his landlord, the aforementioned slave-holder, Frederick Philipse. Given the above, it is difficult to feel too bad for Bernard’s difficulties with his apprentice:

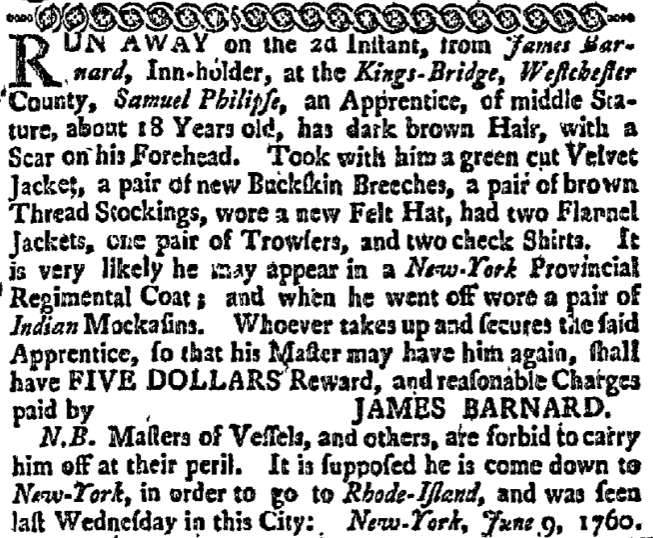

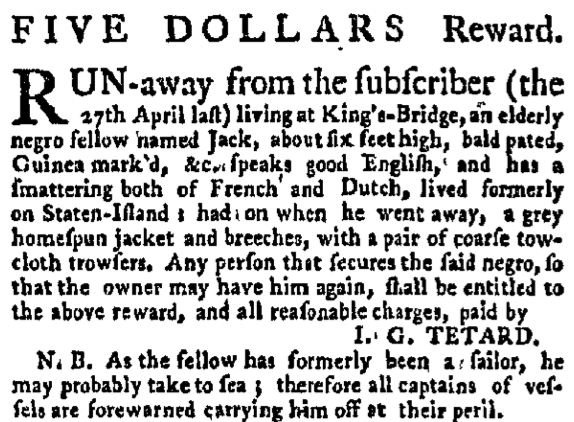

7/21/1760 New York Gazette The note on the bottom hints at the logic of escaping across the bridge to New York City–New York harbor undoubtedly offered the best opportunities for someone looking to make a quick getaway. Just before the revolution, a slave living close to the bridge in Kingsbridge Heights appeared to have had the same idea:

6/13/1774 New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury The fact that Jack, an “elderly” black man is willing to take tremendous risks for his liberty shows that the desire for freedom does not dwindle with old age. As a former sailor who spoke at least three languages it is safe to assume that he had seen much of the world. His unhappiness with being held at Tetard’s boarding school in Kingsbridge could only have been enhanced by his apparently rich prior experiences. Another slave seeking freedom traveled across the bridge in the opposite direction:

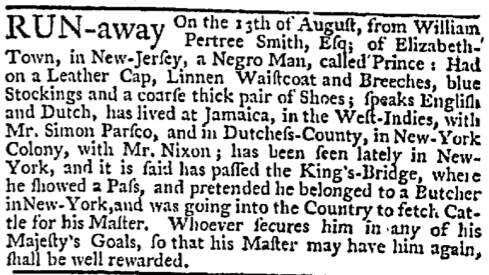

8/28/1758 New York Mercury This ad suggests that Prince not only had a strong desire for freedom but also a quick mind. In addition to speaking at least two languages, Prince was able to procure a pass and concoct a believable story to get past the bridge guard. After the so-called “Conspiracy of 1741“, it could not have been easy for a black person to accomplish such a feat. Once over the bridge, Prince had options. The Albany and Boston Post Roads both began in Kingsbridge for an overland getaway. Plus there were plenty of ferries across the Hudson further north. Who knows how many other indentured servants and slaves crossed the bridge to escape their captivity.

I wonder if the slaves that built the bridge 1693, toiling away for one of the richest men in the colonies, could have imagined that the fruit of their labor would one day become a bridge to freedom for their fellow brothers in bondage.

References

¹ Maika, Dennis J. Encounters Slavery and the Philipse Family, 1680-1751, Dutch New York The Roots of Hudson Valley Culture, Fordham University Press, 2009.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.