Macomb's Mill at Kingsbridge

Early Industry on the Spuyten Duyvil Creek

by Nick Dembowski, 11/11/21

To my knowledge, there are no detailed maps of Kingsbridge between the American Revolution and 1850. But by piecing together scattered records from that time period, you can develop a picture of several sections of the neighborhood. And thanks to the drawings of Jacques Gerard Milbert, the area around the King’s Bridge (at today’s W. 230th and Kingsbridge Ave) is easy to imagine. Sometime in the 1820s, Milbert stood on the east side of Spuyten Duyvil Hill and looked down into the Kingsbridge valley. Today, that view would like something like this:

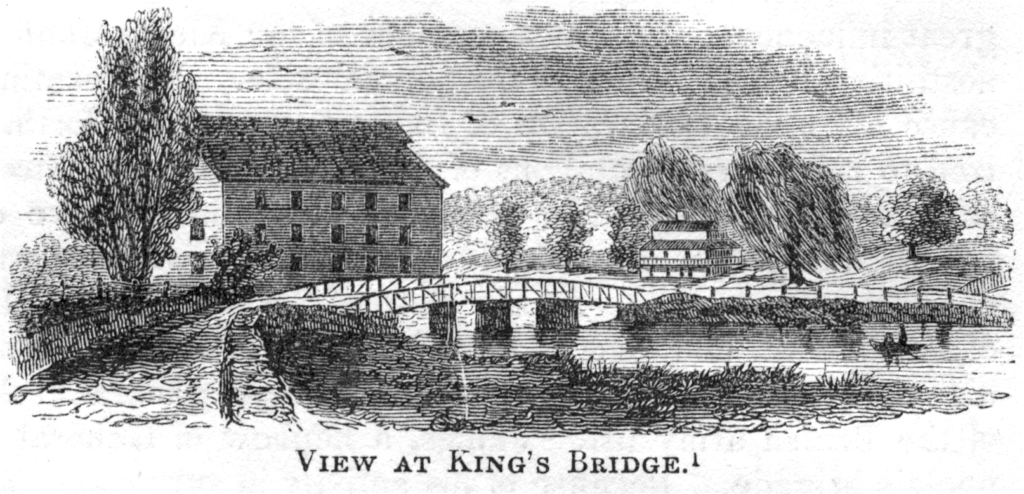

But in the 1820s, it looked a little different to Milbert:

The hills in the background are Kingsbridge Heights and the Spuyten Duyvil Creek is flowing in the center on the same general course as W. 230th Street today. That is Marble Hill on the right side of the creek and today’s Bronx on the left side. The King’s Bridge, which spanned the two sides of the creek, is obscured by large mill buildings. Suppose you were to stand on the other side of the King’s Bridge and look back in the direction that Milbert was standing. That view today would look like this:

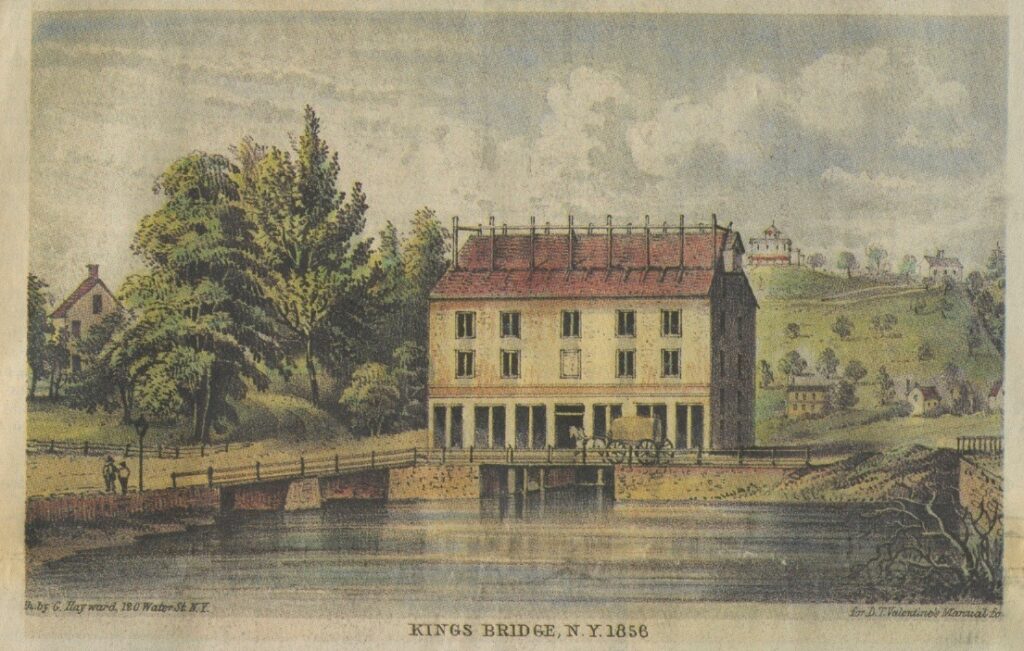

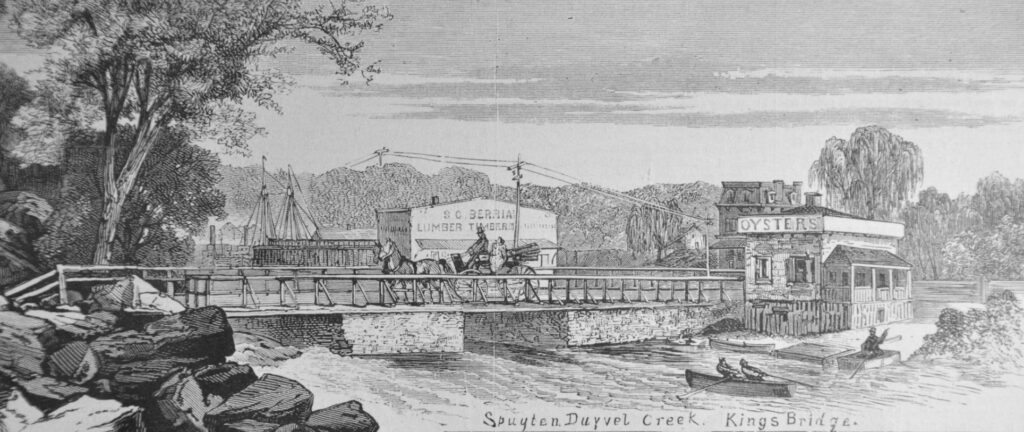

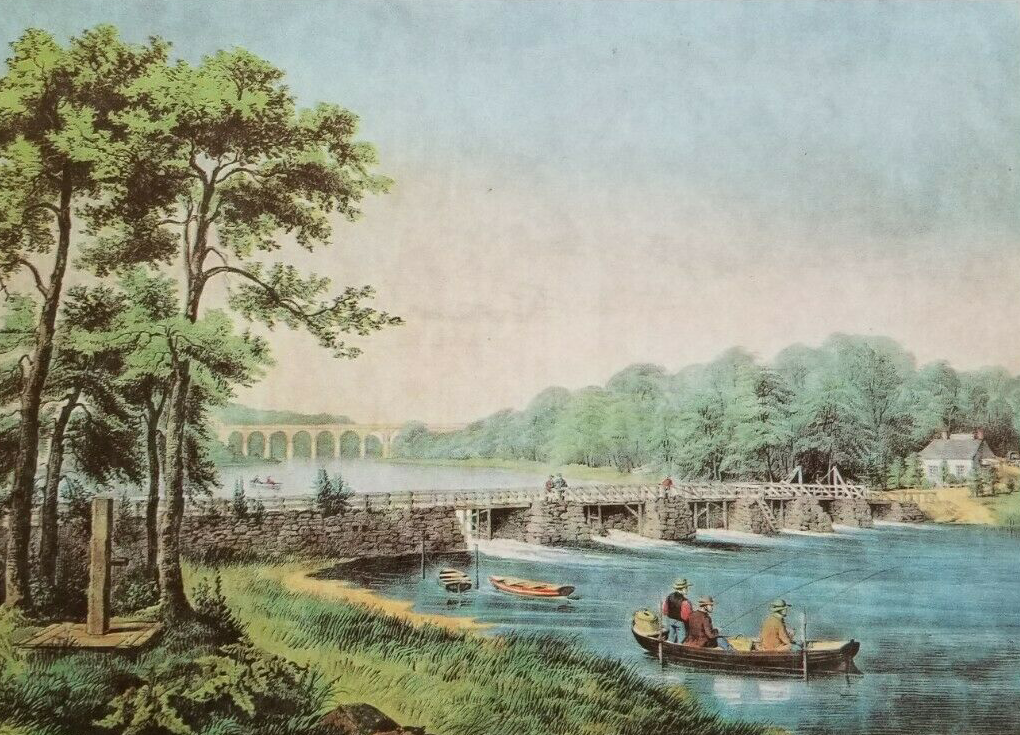

That is the view looking west from the intersection of W. 230th Street and Kingsbridge Avenue. Leafy Spuyten Duyvil Hill is in the background with Marble Hill on the left and Kingsbridge on the right. Milbert never drew from that perspective but another artist, George Hayward, did in 1856:

From this perspective, the Spuyten Duyvil Creek is in the foreground with Marble Hill on the left and a sliver of today’s Bronx on the right. Spuyten Duyvil Hill is in the background. The bridge (located at the intersection of today’s W. 230th and Kingsbridge Ave) is visible because it was on the west side of the large mill building in the foreground.

So what is the story of the mill building that is so prominent in these 19th century prints? It was originally established by the merchant Alexander Macomb, who first purchased a 14 acre lot of land in this area in 1797. That may seem like a lot of land today but it was a small investment for Macomb, who a few years earlier purchased millions of acres of land in upstate New York. Additionally, he owned the grandest home in New York City at 39 Broadway, which became the presidential mansion for a while when George Washington lived there in 1790. Renting his home to Washington was more than a little ironic given that Macomb made his fortune by supplying the British and their Native American allies during the Revolution. Macomb’s property purchases in Kingsbridge included the building that had earlier been a tavern at today’s West 230th and Broadway (where there is now a Dunkin Donuts). Eventually his son, Robert Macomb, would end up living there with his wife Mary.

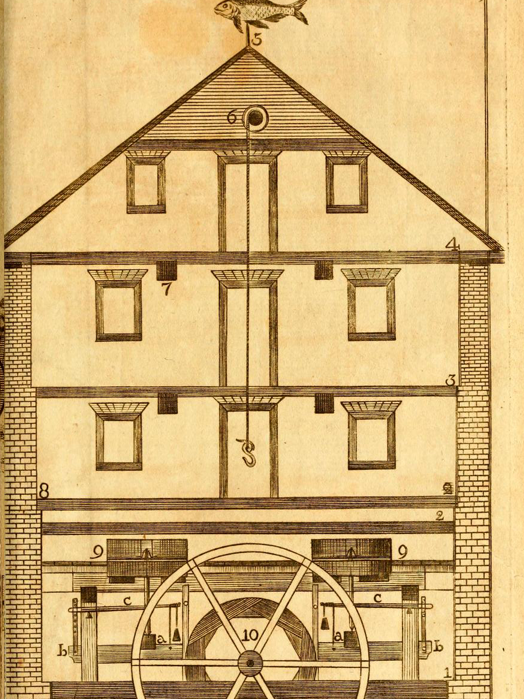

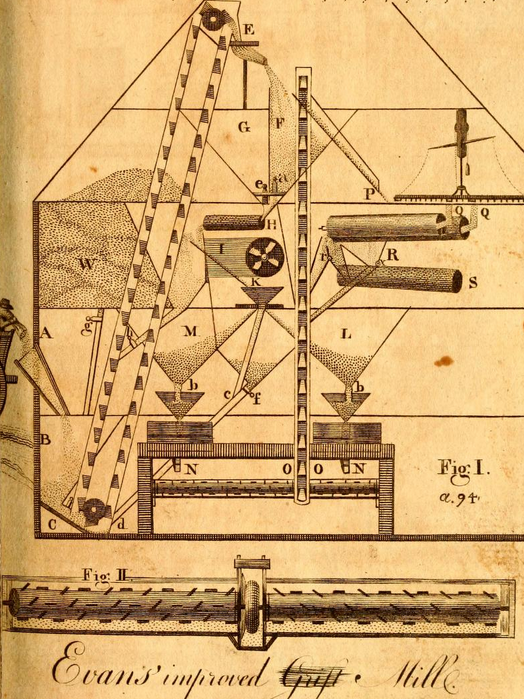

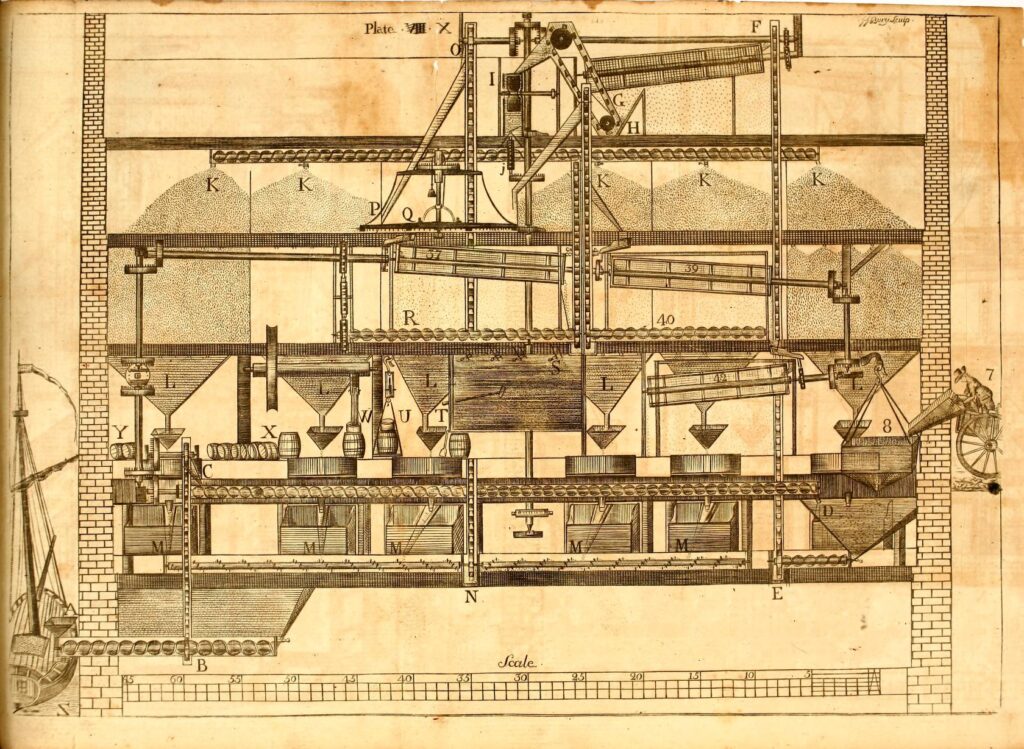

The Macomb gristmill at the King’s Bridge was a major improvement on the neighborhood’s only other mill on Van Cortlandt Plantation, which was a colonial-era structure with two sets of mill stones. Macomb’s mill at the King’s Bridge boasted 9 pairs of mill stones. But even more importantly, it was built using Oliver Evans’ labor saving technology, which allowed one miller to perform the work that required many millers in earlier times. It was a sophisticated piece of machinery as Evans’ 500 page “Young Mill-Wright and Miller’s Guide” would suggest. The guide’s illustrations give an idea of what the mill must have looked like on the inside.

It is a dizzying array of funnels, gears, conveyors, and gizmos evocative of a Dickensian workhouse. The diagram below corresponds to another advantage of the mill’s location at Kingsbridge–access to waterways for shipping. While the Harlem River (east of the King’s Bridge) was too shallow for anything other than small boats, larger craft could pull up to the dock on the Spuyten Duyvil Creek (on the west side of the King’s Bridge) to take cargo to market via the Hudson.

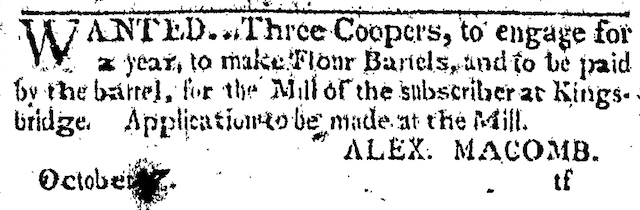

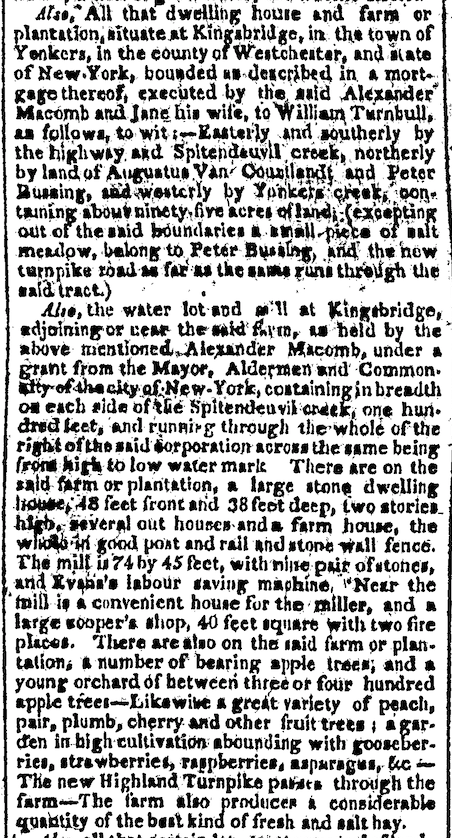

One aspect of this business, the making of the barrels, could not be automated. A workshop of coopers would be required to package the flour:

Advertisement from The Evening Post, October 27, 1803.

Could slave labor have been employed at the mills–to make barrels, mill wheat, or perform other labor? It is certainly possible, if not likely. Alexander Macomb held 12 enslaved Black people in his home–part of a staff of 25 servants.2 In 1812, after Macomb’s mill was sold, he freed an enslaved Black man named Peter Pierson, who continued to live in the Kingsbridge area into the late 1800s. The name Peter Pierson bears some semblance to the name of the enslaved miller working on Van Cortlandt Plantation, Piero, who had a son named Peter. Perhaps Peter Piero’s son was purchased by Macomb from the Van Cortlandts to work at his Kingsbridge mill.

Another possible use for laborers on his Kingsbridge property was on his adjacent farm, which today is the busiest part of the neighborhood (west of Broadway above W. 230th Street). When put up for sale in 1810, it was advertised as a “farm or plantation” with “a number of bearing apple trees, and a young orchard of between three or four hundred apple trees–Likewise a great variety of peach, pair, plumb, cherry and other fruit trees; a garden in high cultivation abounding with gooseberries, strawberries, asparagus, etc– a green house 45 by 15 feet, and 20 feet high, with a great variety of shrubbery and plants.”3 It also noted that the farm “also produces a considerable quantity of the best kind of fresh and salt hay.”

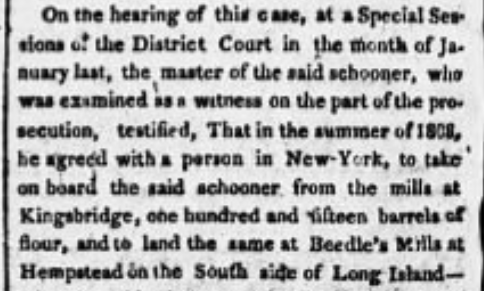

The mill did big business. Although account books have not been found, in 1810 the New York Evening Post ran an article about the seizure of a schooner, the Nancy.4 Apparently, it was confiscated for flouting the young nation’s embargo laws. The article states that the ship picked up 115 barrels of flour from the Kingsbridge mill in summer of 1808. Flour barrels were of standard size: 3 bushels or 196 pounds of flour in each barrel. That shipment alone amounted to over 22,500 pounds of flour produced at the mill at Kingsbridge! But the flour business was not enough to save Alexander Macomb, who was deeply in debt. His land speculation failed to produce the returns he needed to stave off bankruptcy. His property was sold off to settle accounts.

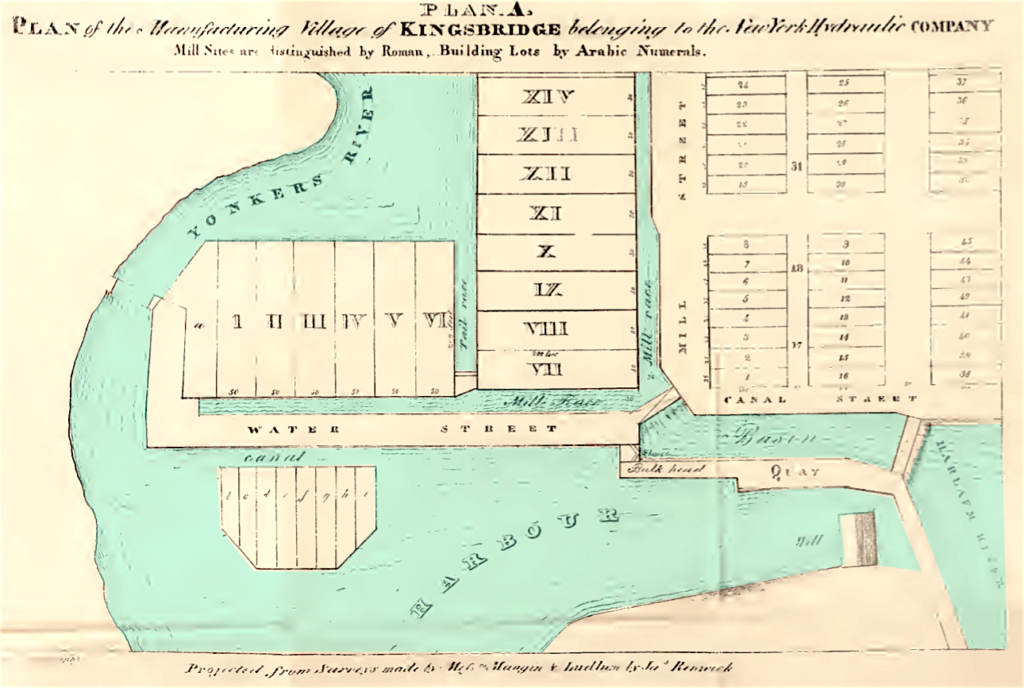

Zooming in on the area around the Kingsbridge, it becomes possible to identify the buildings in the Milbert print using the key to Renwick’s map:

When most Bronxites think of the name “Macomb,” they don’t think of the mill at Kingsbridge at all but rather Macombs Dam Bridge, which spans the Harlem River at Jerome Avenue and 161st Street. In 1814, Robert Macomb had a dam built at that location that played an important role in powering the mills at the King’s Bridge. At high tide, water flowed through Macombs dam into the northern part of the Harlem River, where it was then trapped by the dam. When low tide came around, the northern section of the river would remain at its high level effectively making that whole section of the river into a mill pond. The water could then be discharged into the Spuyten Duyvil Creek at Kingsbridge where the difference in the water levels provided steady and reliable power to run the mills.

As impressive as this was, James Renwick had an even more ambitious proposal for the NY Hydraulic Manufacturing Company. It entailed using Tibbetts Brook and the Kingsbridge valley as an additional reservoir to generate even more power. He depicted his vision in another map–transforming a bucolic setting into “the Manufacturing Village of Kingsbridge:”

Renwick calculated that developing the neighborhood in this way would generate a total of approximately 234 horsepower for milling. It would have completely transformed the area by flooding much of the neighborhood and turning the rest of it into a major industrial center. But the plan never came to fruition. Locals used the waterways for multiple purposes and damming them was, for some, an unwelcome development. Additionally, in 1856 the mill building collapsed during a violent windstorm. Still, it is remarkable to think that the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, now buried under the traffic of W. 230th Street, was for a while the engine of early industry in our area.

Questions, Comments? Post them here.

Notes and References:

1 – James Renwick also happened to be the father of the architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the grandfather of James Renwick Brevoort, a well-known painter of the Hudson River School.

2 – Portrait of an Opportunist: The Life of Alexander Macomb by David B. Dill, Jr. (worth the read!)

3 – Public auction notice in 5/14/1810 New York Evening Post:

4 – 3/14/1810 The Evening Post:

5 – Tieck. Riverdale, Kingsbridge, Spuyten Duyvil. p. 16.